Receipt in full in red ink- Captain Warren P. Edgarton at Stones River

The Battle of Stones River, for a multitude of reasons, is my favorite Civil War battle to study, and like so many of the bloodiest battles of the war, there are certain stories, themes, and even legends that arise that become part of the lore and canon of the battle. Among my favorite stories are ones about the capture of flags and artillery pieces, the true trophies of battle, and that is the focus of today's post- the capture of Battery E, 1st Ohio Volunteer Light Artillery by the Texans of Ector's brigade in the opening moments of the battle on December 31, 1862.

| Union artillery in line at Stones River- author photo from May 2005. |

One of the most infamous pieces of battlefield lore made the rounds of the Army of the Cumberland after the Battle of Stones River arose from the fact that the veteran troops of Brigadier General Richard W. Johnson's division had been surprised and routed at the outset of the battle. I have come across dozens of accounts from AotC veterans who laid the entire blame for the disaster that befell the Union right wing squarely on General Johnson's shoulders. But one of the most common complaints soldiers made was the issue of lack of preparedness, the most dramatic symbol of which was the charge that Johnson was so ill prepared that he had sent "all of the artillery horses off to water," such that when the Confederates hit at around 6:30 A.M., the artillery couldn't be maneuvered into position or extracted from the field once it became clear that the two brigades in this sector (Willich's and Kirk's) could not hold the position. The charge was both unfair and unjust, and only time would correct it, but Johnson's reputation for a while was rather seriously tarnished by this incident. General Rosecrans, however, cited Johnson for gallantry at the battle and focused a portion of the blame on a junior officer: Captain Warren P. Edgarton.

NASHVILLE , TENN. June 25, 1863

| Location of Battery E, 1st OVLA circled in red from troop location map drawn by Ed Bearss, Stones River National Battlefield Park |

This facet of the battle is of great interest to this blog as the focus here is in telling the story of Ohio's soldiers in the Civil War, and the two batteries that comprised the artillery on the far right wing were both Ohio batteries. They included Battery E, 1st Ohio Light Artillery under Captain Warren Parker Edgarton which was attached to Brigadier General Edward N. Kirk's brigade, and Battery A, 1st Ohio Light Artillery under First Lieutenant Edmund Bostwick Belding which was attached to Brigadier General August Willich's brigade.

Both batteries took heavy losses in the opening moments of the battle- Battery E's six guns were captured entire, while Belding lost three of the battery's six guns, but it was Edgarton who came under particular censure for his supposed negligence in allowing his horses to be taken off to water. (Belding's horses presumably remained with the battery, but as no official report was filed for the battery, one is left to wonder.)

Following the battle, First Lieutenant Albert G. Ransom wrote the official report for Battery E as Captain Edgarton had been captured while bravely manning his guns during the opening moments of the battle. He reported that "at daylight on the morning of the 31st instant, the pickets gave the alarm, and skirmishers were firing, but as yet could see no enemy. The horses were quickly hitched, except a few, perhaps one-half of which were on their return from water, and were brought up at once. Failing to distinguish the enemy, two shells were thrown in the direction of their fire, and, when they appeared, canister. Six rounds were poured into the moving mass with great effect, but, attacked in front and flank, we soon saw our horses shot down, the work evidently of sharpshooters, who moved in the advance and on the right and left, until the whole column being now upon us, we had not horses enough to save our guns." Ransom continued, "allow me to express my heartfelt regret at the loss of Captain Warren P. Edgarton, whose manly voice rang out above the din of musketry, encouraging his men, and giving orders coolly and judiciously. He preferred to go a prisoner with his battery to leaving his much cherished pieces."

Ransom rather deftly handled the later controversial question about the location of the horses by acknowledging that some were being watered, but rightly laid the blame for the capture of the battery to the Confederate sharpshooters who shot down many of the horses that remained. His report was written a week after the battle, before press reports of the surprise of Johnson's division started to circulate. But what really hurt Edgarton's reputation was not the reports in the press (of which there were many), but the specific citation that General Rosecrans used in his own official report, in which Captain Edgarton was specially mentioned as being "guilty of a grave error of taking even a part of his battery horses to water at an unreasonable hour and thereby losing his guns." It is significant that Rosecrans' report cites only four officers negatively- two for cowardice in the face of the enemy (recommended for dismissal), one for drunkenness (recommended for dismissal), and Edgarton for an error of judgement.

|

| Major General William Starke Rosecrans |

So one is left to ask- was it unusual for members of a battery to take their horses off to water in the morning? Was it, as Rosecrans charged, a grave error of judgement? Well, no. In John Billings' classic Hardtack and Coffee, Billings spends considerable time discussing the normal morning routine for artillery (at least in the Army of Potomac and likely not very different in the Army of the Cumberland) that one of the first items of duty was taking the battery horses to water, and to then feed them. So Edgarton's men taking the horses off to water shortly after dawn was part of the normal morning routine of the battery, and in no way suggested neglect of duty or a lack of vigilance. I would offer that nearly every other Federal battery did the same that morning- the Union army was on the offensive, and did not expect an attack from the Confederates. Animals need to be properly watered and fed if they are going to perform the work needed to support the offensive Rosecrans had planned, hence, there is no reason why the horses shouldn't have gone to water that morning.

Additionally, even though the battery was in the presence of the enemy, they were hardly alone- they were nestled in the midst of two veteran brigades of troops totaling roughly 4,000 men. As Edgarton argued in his report, "I was completely surrounded by veteran troops. I had a right to suppose that our front and flank were so picketed that I should have notice of the approach of the enemy. I ordered a half battery of my horses to go to water on a sharp trot, and return at the slightest indication of danger. The horses had barely reached the water when a fierce shout was heard at the front, and a terrible volley of musketry was poured in upon us." The Confederates had achieved surprise, and had caught the Union army in the midst of preparing for the efforts of the day. This achievement is more a result of superb timing on the part of the Confederates, not negligence on the part of the Federals.

As such, Rosecrans' snub of Edgarton in his official report starts to smell to this researcher as an attempt to protect the reputations of those in high command who were responsible for security in this sector (Johnson, McCook, and ultimately, the commanding general himself) and shift some of the blame for the disaster to a junior officer, then a prisoner of war. Not one of Rosecrans finer moments in my opinion.

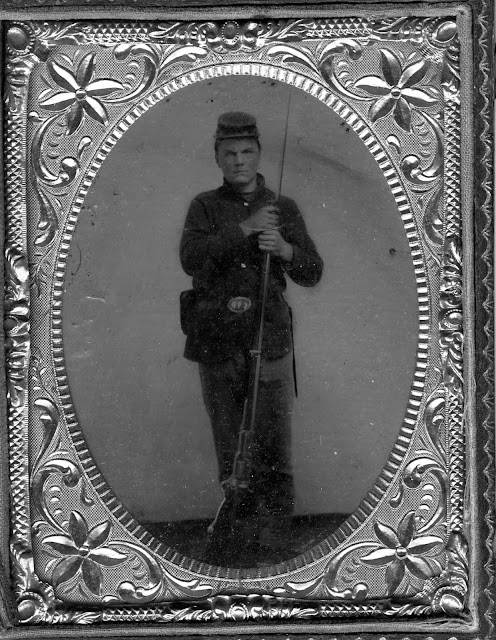

| Captain Warren Parker Edgarton, Battery E, 1st Ohio Volunteer Light Artillery |

A few years ago, I came across a text for artillery officers dating from the 1890s that had an interesting passage that directly speaks to Edgarton's case. "An artillery officer should merely take care that each lost piece is well paid for by the enemy, and he should be able to repeat the gruesome pleasantry of the battery commander who said, "I lost my guns, but I took the enemy's receipt in full in red ink." The end note compliments Edgarton for his battery's work at Stones River and laments that "such were the mistaken views that were held at the time in regard to the loss of his guns, that he seems to have been censured for losing his battery rather than complimented for his gallant action." This is a direct jab at Rosecrans' report, and I think is spot on.

Edgarton certainly didn't receive plaudits (and I don't think he received the court of inquiry asked for in his official report), but he retained his command and ended the war as one of Sherman's respected chiefs of artillery.

Whether his guns were dearly bought is another question- the Texans that captured the battery (Ector's dismounted cavalry brigade) suffered 357 casualties (nearly a third of the command by Ector's report) during the battle, a goodly portion of which were sustained in their assault on Kirk's brigade at the outset in which they captured not only the colors of the 34th Illinois Infantry, but also Edgarton's battery. Dearly bought- a matter of opinion but it sounds like the answer is yes, especially given the short time the battery was in action that morning.

When I think about this aspect of the battle, what strikes me is that this incident is in many ways a repetition of the mindset that pervaded the Union high command in the days leading up to Shiloh. There, Union commanders had an offensive mindset that couldn't conceive that the Confederates would leave their entrenchments in Corinth and make an attack at Pittsburgh Landing. The men did not entrench, and when the Confederates attacked, the Union army was hard pressed to hold them back.

At Stones River, we see a variation on this same theme. As Rosecrans' army was on the offensive, one wonders that his commanders felt the same way as Grant's did before Shiloh: confident that the enemy would respond the way they expected them to, i.e. stay in their entrenchments and wait for the Union army to come to them. That had been happening for the past five days, why wouldn't that continue? Besides, wing commander General Alexander McDowell McCook was breezily confident that he could hold his ground for several hours if attacked (and eventually did (if just barely), largely due to the hard fighting of Davis' and Sheridan's divisions) which would give time for the offensive Rosecrans had planned to be executed by Left Wing troops under Thomas L Crittenden to push back the Confederates beyond Stones River. This would negate any offensives by the Confederates on the west side of Stones River; at least this was the thinking.

|

| Brigadier General Edward N, Kirk Died of his Stones River wound in July 1863 |

With the exception of a few brigadiers (Joshua Woodrow Sill in particular), the Federals on the right wing were just a bit too confident and sure of themselves this time, and the result proved to be a disaster. Rosecrans and his generals, like his former commander Grant, had focused too much on what he was going to do to the enemy, and made inadequate provision for what the enemy might do to him. As such, the success of the Confederate flank attack at Stones River (like a similar one against another Union right flank five months later at Chancellorsville) is a textbook case of the importance of constant vigilance in the face of the enemy, and a warning against hubris on the part of those in command.

Consequently, Captain Edgarton, along with General Willich and 37 other captured Federal commissioned officers, was sent south from Murfreesboro on January 2nd, stopping in Chattanooga and being imprisoned for a time in Atlanta, before he was sent to Richmond and exchanged in April 1863. Edgarton returned home to northeast Ohio and while home, gave a series of talks in several town halls giving a description of his experience at Stones River and his subsequent imprisonment.

But it was six months before he had the chance to make an official report of what happened at Stones River, and in so doing, he demanded a court of inquiry to investigate his conduct.

Edgarton's official report, reprinted below from the O.R., gives his side of the story:

COLONEL: I have the honor to submit, for you consideration, a brief report of the action of my command (Battery E, 1st Regiment Ohio Volunteer Light Artillery), at and immediately preceding the battle of Stone's River.

I have cause seriously to regret that my capture and subsequent imprisonment have so long delayed to recital of facts which I purpose to embody in this report, known only to myself, by which injustice has been done to the brave of my command, especially as there seems to have been very generally a misapprehension in regard to my position on the morning of the 31st of last December, and the cause which resulted in the capture of my battery.

We left camp near Nashville on the 26th of December, attached to General Kirk's brigade of General Johnson's division, right wing. We marched on the Nolensville pike. The next day, the 27th, approaching Triune, our brigade was ordered in the advance. After marching about 1 mile, we encountered a battery of the enemy posted in a commanding position. My battery was ordered forward to engage it, and, after a few rounds, we drove them from that position. We took a second position on a hill overlooking the village of Triune

The duty of following the enemy on this day was very arduous. We were obliged to leave the traveled roads in order to gain position; we removed, dragged our pieces through the soft ground of cultivated fields, through streams of water, and climbed hills, where it became necessary of call for a detail from the infantry to help us along.

On the 29th we took the direction of Murfreesborough, passed over a very rough and hilly road, and arrived after dark near the scene of the contemplated battle. The utmost caution and vigilance was ordered. We were hitched up and ready for action at daylight of the 30th.

On this day the Second Division was held in reserve. We followed the advance till late in the afternoon, when we were ordered to oblique to the right, to cover the right of General Davis' division. The enemy had posted a battery on the right of General Davis, in a handsome position, enfilading his whole line. General Kirk ordered me forward with a regiment of infantry as support, with instructions to silence, if possible the rebel battery. Under cover of a cedar thicket, I was enabled to approach within about 700 yards of the enemy. The battery was silenced by six rounds from our pieces. They retreated, leaving a caisson disabled. An attempt was made to gain another position, but we followed them engaging the infantry that came to their support, and kept up a brisk fire until dark. General Kirk the ordered us to cease firing.

My battery was the only detachment of General Johnson's division engaged in the action of Tuesday, the 30th of December. I here represented to General Kirk that my men were very weary, my horses almost famished; that my ammunition was short in the limber-chests of the pieces, and asked permission to withdraw long enough to prepare for hard work on the following day. Believing horses to be the main dependence of a light battery, and not knowing when I should have I should have an opportunity to feed and water it brought into action, I asked time to prepare for the conflict of the morrow. General Kirk pointed out a spot about 100 yards in the rear of the position I then occupied, sheltered by a heavy growth of timber, and ordered to bivouac there for the night. I reported to him that I could not place my guns "in battery" there, or defend myself if assaulted. He replied that I should be protected, and that ample notice should be given when I was expected to take a position in the line of battle.

After I had brought my guns into park, the right of the brigade was thrown across the muzzles in front. General Willich's brigade marched up and formed on the flank. I found myself within the angle formed by the junction of the two brigades, retiring about 50 yards, and on a low and narrow piece of ground. I have before stated that it was dark when I arrived at this point. We were not permitted to have lights. The ground in our rear had not been reconnoitered. I rode back some distance, but failed to find water for my horses. I did not consider it safe to push the investigation far outside of our lines that night. I waited until morning. At daylight a small stream was discovered about 100 rods in our rear. It was quiet all along our lines. I could not hear a picket shot, nor any indication that the enemy was in our vicinity. I had no orders to take position. My horses were already harnessed, to hitch on at a moment's warning. I was completely surrounded by veteran troops. I had a right to suppose that our front and flank were so picketed that I should have notice of the approach of the enemy. I ordered a half battery of my horses to go to water on a sharp trot, and return at the slightest indication of danger. The horses had barely reached the water when a fierce shout was heard at the front, and a terrible volley of musketry was poured in upon us. I called the cannoneers to their posts, had a half battery hitched in, put my guns in battery where they were, and a moment was prepared, as best I could, to fight in that position. The infantry, our support, gave way on the front and flank in disorder, almost with the first volley. I then opened on the enemy with canister, firing from 16 to 20 rounds, with good effect, as I have cause to know, for I passed over the ground in our front a few moments afterward a prisoner.

The assault of the enemy was fierce and overwhelming. After the first fire, in which I had 1 man killed, a number wounded, and 12 horses killed, the enemy charged with an impetuosity which carried everything before him. The battery was taken.

It would have been impossible for me to have saved my battery, even if I had commenced a retreat on the first alarm. The enemy was very near us before discovered, and the fight commenced without any of the preliminary skirmishing before a general engagement. To the best of my judgment, it was not more than five minutes from the firing of the first shot to the catastrophe when my battery was taken and myself a prisoner. In the mean time some of my horses returned, were hitched in, and killed. The rest were driven back by the fierce fire from the front. I deemed it my duty to stay with my guns so long as a single shot could be fired, or a chance exist of their being supported and retaken. I did not realize the helplessness of the case until I was surrounded and retreat impossible.

In the brief time we were engaged I had 3 men killed, 25 wounded, and 22 taken prisoners.

I wish here to compliment my men for their determined bravery; they obeyed orders implicitly, and stood by their guns to the last.

I would not be understood in this report as casting the slightest reflection on the discretion or vigilance of my brigade commander. I am not capable of criticizing his orders, nor would I be permitted to do so had I the disposition. I had learned highly to respect General Kirk as a fine gentleman and accomplished soldier. I reverenced him for his heroic courage in the presence of an enemy. He was dangerously wounded in a desperate attempt to rally his broken regiments to support my battery, riding almost upon the bayonets of the enemy.

As I have been charged with grave errors on the occasion of the battle, I respectfully request that I may be ordered before a court of inquiry, that my conduct may be investigated.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

Warren P. EDGARTON,

Captain Battery E, 1st Regiment Artillery, Ohio Vols.

Comments

Post a Comment