Interview with Brad Quinlin and the story of Pierre Starr, 39th Ohio Infantry

This week’s post is

going to deviate from my normal theme but I think you will find it a worthwhile

change of pace as I am featuring a question and answer session with noted Civil

War author Brad Quinlin. We will discuss

his newest book For My Grandchildren: The Civil War Journey of Pierre Starr,

and share an excerpt from the book which discusses the Battle of Corinth. The

156th anniversary of this small but important Civil War battle is

this Wednesday and Thursday so without further ado…

|

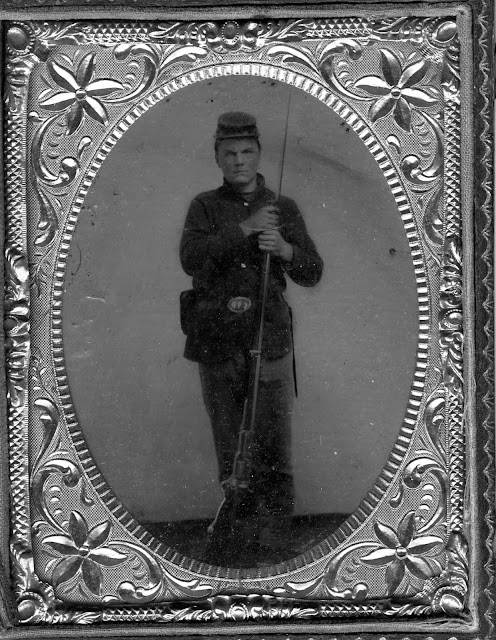

| One of the "Boys of '61" (Wood County Museum) |

Brad and I go back a

number of years, each of us sharing a passion for telling the forgotten stories

of the Civil War. I first met Brad back in 2007 when I attended a reunion in

Georgia for descendants of the 21st Ohio Infantry and along the way

we developed a friendship rooted in our mutual fascination with “the boys of

’61.”

You may know Brad from

television, as he was featured in the show “Who Do You Think You Are”; the

episode in particular was one aired in 2010 where Matthew Broderick (who

famously portrayed Colonel Robert Gould Shaw in the 1989 film Glory) discovered that one of his Civil

War ancestors, a member of the 20th Connecticut Infantry named

Robert Martindale, was killed outside of Atlanta and buried in Marietta

National Cemetery. Brad, who for years has been working to identify unknown

graves at Marietta, was able to show Broderick the unknown grave that contained

the remains of his ancestor. It was a powerful moment to watch.

Brad’s latest book is

entitled For My Grandchildren: The Civil War Journey of Pierre Starr and

features the wartime letters and postwar memoir of Surgeon Pierre Starr of the

39th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. Right off the bat, one of the things

that intrigued me was that Starr was not an Ohioan at all- he was a native of

Connecticut. He joined the U.S. Army in New York in the summer of 1862 as a

contract surgeon and was sent west to join Grant’s army in northern

Mississippi. Initially assigned to the ill-fated 11th Ohio Battery

(which would be decimated weeks later at the Battle of Iuka), he did not find

the situation congenial and asked to be reassigned. He was assigned to the 39th

Ohio and thus began Starr’s lengthy tenure with regiment, one of the members of

Fuller’s Ohio brigade (27th, 39th, 43rd, and

63rd Ohio) that rendered distinguished service as part of the Army

of the Tennessee.

|

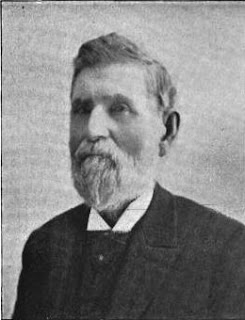

| Assistant Surgeon Pierre S. Starr, 39th Ohio Volunteer Infantry (Brad Quinlin courtesy of Robert Starr, III) |

D- You have been active in Civil War research for many years- what drives you to keep going?

B- I

love the journey for the next find. No matter if it is at the National Archives

in Washington D. C. or the National Archives divisions across the United

States. It can even include the college libraries that dot the country. I am

always looking for the next find that will help me to better understand the

events of the American Civil War and the journey of each of the men.

D- Please describe the circumstances under which you came to know about Pierre Starr's account.

B- I

got a call from an old friend and reenacting buddy Don McGilvary. He said he

was up in Connecticut to visit his cousin and she had told him that there was a

great collection of Civil War letters and a man named Bob Starr had all of them.

Bob had tried for 30 years to get them published after he found them in the

attic of the old family home and no one would do it. Bob Starr is the great-grandson of Pierre

Starr. So, Don mentioned me and the other books I had written. Bob Starr gave permission

to Don to give me the narrative part of the collection to look over and see

where it might take us.

So, I got the narrative that Pierre had

written as a gift for his grandchildren. When I read the narrative that Pierre

had written for his grandchildren, (Bobby and Sally) I knew this was a gem of

Civil War documentation. But it was written in 1912 and I knew many in the

Civil War community would bash it. I called Bob Starr and told him what I

thought, and he said did you see the numbers on the sides of the narrative

pages. I said yes. Well my great grandfather used the many letters he wrote

home during the war to refresh his memory for the narrative. I asked Bob, “Do

you have the letters?” Bob said yes, had all the letters and a couple of photos

of Pierre from during and after the war.

D- Your work, like mine, is driven by soldier narratives- the stories of the men in the ranks. What about this particular facet of Civil War history interests you, and why?

B- I

have always been interested in the common soldier and his story. I had many

family members who fought in WWII, Korea, and Vietnam. Sixteen ancestors fought

in the Civil War on both sides of the line-Confederate and Union. I listened

and asked questions of my uncles and my father-in-law about his WWII service.

My father was a WWII combat wounded vet. So 32 years ago I took a dive head

first into the study of the Civil War.

It was the soldiers’ stories that I wanted to tell.

D- As a Massachusetts native living in Georgia, have you seen any changes in general attitudes towards Northerners since you first moved to the South? If so, what changes, and have they benefited or hindered your work?

B-

When I moved to Georgia in 1982 as Yankee born and raised it was very

interesting. What was a joy for me is I had ancestors that fought on both sides

of the war. I had ancestors from both sides that died during the war. Even with that I was called a “damnYankee.”

Yes, just one word, I had always thought it was two words.

After a few years of Civil War research,

I discovered new research from the Confederate side, that helped identify 350

Confederate soldiers’ burial sites, and now I am working on identifying more

Confederate grave sites. So, I am well received and asked to speak at many

United Daughters of Confederate groups and Sons of Confederate Veterans Groups.

Three years ago, the Kennesaw Tent of the Daughters of Confederate Veterans

gave me the highest award that they present, the Jeff Davis Award. I was given

this award on Confederate Memorial Day 2015.

D- When conducting your research, do you have specific things that you are looking for? What makes you "pop" when you find it?

B- When

I start a research project I have a specific list of items to research. I go to the area of the archives or library

to find documents that are needed for the research project and I pull the files

and file numbers. When you pull a group of documents you start to look for the

documentation and proof for that specific project. But you are going to gather

documents that will lead you on a path you never expected. I never research

with blinders on. I will not let my research be driven on the one path. I let

the documents take me on the journey and almost always you find something you

never expected to find.

What makes me pop? Always finding new

things that have never been used or found in other research. My favorite must

be my 21-year research project on gathering the names of every man of African

descent who was in Sherman’s army in the Atlanta campaign, March to the Sea,

and the Carolina campaign of 1865. That research journey has been very

important to me. I have found letters those men wrote. The best find was a tin

type photo of Hosea Simmons, an undercook of African descent. A copy photo of

that image is being used at the National Museum of African American History in

Washington D.C. It is also being used on a wayside exhibit at Kennesaw Mountain

Battlefield and at the Atlanta History Center. This image had been hidden in an

envelope in Hosea’s pension record since 1902. I found it and let out a big

YES. Everyone in the research room of the National Archives knew I had found

something special.

D- Pierre Starr left a riveting account of his Civil War experience. What is your favorite story from the book and why?

B- That

is maybe the hardest question to answer. I have so many. When I first read the

narrative, it was one A-Ha moment after another. If I had to pick one thing

from the book it was the letter Pierre wrote home to his mother on October 2,

1864. Pierre had gotten on his horse and rode around Atlanta describing each

street and building and then got off his horse and went into one of the fine

homes of Atlanta. We do not have a narrative from a Union soldier who describes

a home in Atlanta after the evacuation of General Hood’s Confederate army. This is one of the best letters I have ever

read.

D- I will be featuring an excerpt from Starr's account of the Battle of Corinth as part of the blog post; what sticks out to you as particularly insightful from Starr's account of this battle?

B- The

depth of Pierre’s description of the town of Corinth and the movements of his

regiment and brigade are very important to the story of Corinth. But the

description of the battlefield in its aftermath. Pierre talks about the dead of

both sides and how they are strewn across the battlefield, along with the

debris of the battle.

D- My blog features numerous stories of life on the battlefields of the Civil War- which battlefield intrigues you and why?

B- Each

Civil War battlefield has so much to offer, and each in a very unique way.

Chickamauga Battlefield, the first national battlefield, has a vast landscape

that encompasses the two days’ fight on September 19-20- 1863. You can walk the

battlefield and sometimes for hours be the only one in that part of the

battlefield. Then of course Gettysburg is The Civil War battlefield. It

has so much to offer to the visitor. It takes you over the three days’ fight

and then the town has so much to offer in additional information. Then Shiloh,

Sharpsburg, Wilderness, Vicksburg, Richmond. Need I go on as each has its

importance in the study of the journey of the Civil War soldier.

D-

Where can readers go to purchase a copy of For My Grandchildren?

B- It is available through Amazon or if they would like a signed copy, they can contact me at 21stohio@charter.net or www.tolearnyourhistory.net.

Where can readers go to purchase a copy of For My Grandchildren?

B- It is available through Amazon or if they would like a signed copy, they can contact me at 21stohio@charter.net or www.tolearnyourhistory.net.

Well-written soldiers’

narratives always pique my interest, and I think that the reader will find

Starr’s account of the Civil War compelling reading. His story encompasses

three years of camp life, marches, campaigns, and includes his experiences in

some of the bloodiest battles of the war, including Corinth, an excerpt of

which is included next. In addition to Starr’s personal letters, a few letters

from George Cadman of the 39th Ohio are included that lend some

additional insight into the events that Starr witnessed. Starr’s letters closely follow the

regiment for much of its service, but he did find himself temporarily assigned

to other units at various periods of time, including one memorable stay with a

regiment of colored troops stationed near Athens, Alabama. As such, the reader

will enjoy a rich, detailed account of the Atlanta campaign, and subsequent

March to the Sea, along with the Carolinas Campaign.

Account of Assistant Surgeon Pierre Starr, 39th Ohio Volunteer Infantry

of the Battle of Corinth, Mississippi, October 3-4, 1862

On Friday October 3rd, the Rebel force was largely increased and the fighting about four miles outside of Corinth became quite severe. The wounded then began to arrive and by evening we had a large depot and the two hotels, the Tishomingo House and another one on the other side of town, filled with them. Among these were two of our generals, Hackleman of Indiana and Oglesby of Illinois. I was in the room with Hackleman where he was lying in full uniform on a couch breathing his last. His robust frame and strongly developed muscles indicated a man in the acme of efficiency in marked contrast with his pallid face and labored breathing. His adjutant was kneeling by his side with an ear close to the dying General’s lips to receive the last faltering words for the family at home. (Editor note- both generals were housed at the Tishomingo Hotel and Hackleman’s last words reportedly were “I am dying, but I die for my country.”) General Oglesby was in an adjoining room, shot through the lungs and not expected to survive the night. He, however, recovered, returned to the army, and was afterwards Governor of Illinois.

|

| At Corinth, Starr witnessed the final moments of Indiana brigadier Pleasant Hackleman. "I am dying, but I die for my country," he reportedly whispered to his adjutant. |

Late in the afternoon, the fighting had got quite close and the cannonading and musketry was rather disquieting, particularly since it was apparent that we were getting the worst of it. Massed columns rushed forward to meet them with flags flying and drums beating. The cheers of our men and those of the enemy were distinctly heard as one or the other made a successful charge. Night brought an end to the contest for the present; we had nothing over which to be jubilant. All seemed depressed as they gathered in crowds about the hospitals and other places, the incidents of the day were narrated, and anticipations of the morrow discussed. All were serious; on the morrow would be the decisive battle, and if no more successful, we would be badly whipped and prisoners or worse by the next night.

I had been working to the limit all that afternoon attending the wounded of whom there were many hundreds and felt used up. So about midnight, with a couple of friends, I went to a private house for there were a few families still remaining in town, roused the inmates and announced our intention of spending the remainder of the night. We were not welcomed but that made no difference. During the night of the 3rd, the Confederates were heard planting a battery a few hundred yards from our redoubts and about 4 A.M. on the 4th we were aroused by the heavy booming of artillery. The enemy was furiously shelling the town, and I got a reluctant acquaintance with their formidable missiles. After watching the fusillade for a few minutes, we started for the hospital.

Now if there is any time when one feels less valorous than another it is about 4 o’clock of the chilly morning when one is empty of stomach, tired in body, and depressed in spirits and screaming shells are bursting over one’s head. It seemed to me that I was doomed as, one after another, they came with their blood curdling hisses, as if they were huge steam locomotives hurtling through the air and then bursting with terrific clamor into a thousand jagged instruments of death. One crouched involuntarily, as if from the loudest thunder clap. Then before one could straighten up and realize that he was not torn to bits, another shrieking demon of destruction would explode with a deafening roar. To state it mildly, I was just then uneasy about my temporal welfare and someplace, anyplace far from the seat of war would have been agreeable. Yet if one could eliminate the personal equation, he might admire the graceful curves of these engines of destruction and delight in the fiery trails their fuses left behind in their furious flights through the darkened sky.

| Death of Colonel Rogers at Battery Robinett. Starr's regiment lay in reserve behind the front line of Fuller's Ohio brigade during the fierce fighting there on October 4, 1862. |

But we hurried on to the hotel, which was filled with our wounded the night before, to find that because of its proximity to our line of defense, nearly all had been removed farther to the rear. A few minutes before we reached the hotel, it had been struck by a shell, the victim of which lay mangled and dead at the foot of the stairs and over whose body we had to step. Welcome daylight had now come and the four guns of the Rebel battery which had been shelling us were silenced by the Parrott guns of Fort Williams and two of them taken by our infantry. Skirmishing then opened at various points in our front, constantly increasing to the magnitude of a battle.

Outside of our breastworks were 40,000 men of the combined forces of Generals Price and Van Dorn, the grand army of the west. Inside were 25,000 men under Rosecrans to defend the town. While greatly outnumbered, we had the advantage of artillery of which the enemy had but little and we were on the defensive behind breastworks.

About 9:30, threatening masses of Confederate troops were suddenly discovered, assuming a wedge like form and impetuously advancing. Now our batteries opened and made hideous gaps in their lines. As the Rebels assaulted, a whirlwind of bullets, grapeshot, and canister poured into their fears, but, as if insensible to fear, they pressed on. Again and again with the greatest bravery and recklessness they assaulted and our cannon on the right and left were blazing with an almost continuous roar, while the crack of the enemy muskets could be heard very close when the noise of the heavy guns would permit.

Hundreds of Confederates crossed the ditch in front of our works, climbed into the forts, and clubbed the men at the guns only to be shot down. The head of the enemy’s main column reached within a few feet of Fort Robinette, and Colonel Rogers with a Rebel flag in one hand and a revolver in the other led his men straight up to its crest. He was shot down by one of our drummer boys who had crept to the firing line, seized a musket of a disabled soldier, and made good use of it. Colonel Rogers was said to have been the fifth standard bearer who had lost his life at that point.

One of our divisions wavered, fell back in considerable disorder, and a panic was barely averted by strenuous work on the part of the officers. All around, the enemy made a most desperate charge in solid columns, though whole companies seemed to go down as the shells ploughed through them. The firing was closer, and the enemy was in town. Rosecrans’ headquarters was reached and hand to hand combat was waged in the streets. Commissary wagons were seeking a place of safety, ammunition trains were on the run, and intense excitement prevailed.

Musketry firing on the part of the Rebels seemed redoubled and bullets whizzed about most flagrantly, and our cannons were belching out a deafening roar. Orderlies on their horses were galloping and it looked like a panic, though in truth, there was none since the seeming confusion was but the hurried execution of orders, and the double quick movement of the troops from point to point as exigency demanded quick movement of the troops from point to point. Now we had orders to remove the hospitals further from town, and we began to comply when the pleasing assurance came that the wounded were safe in their present quarters and the enemy was repulsed.

We had lost much ground when the defection of General Davis’ division began, and Fort Richardson seemed about to be taken as the Rebels rushed in with a yell, but the 56th Illinois made a charge and held them, when our whole line advanced and the Confederate columns were broken and they fled to the woods. The battle was over by 11:30. I was not aware until then, having been busily engaged by the order of the division surgeon, in attending the wounded as they fell. As soon as the enemy was known to have retired, another surgeon and I took an ambulance for the battlefield after the wounded.

There were awful sights: the dead and wounded, friends and enemies, mangled and torn in the unseemliest manner. Many were without heads, others armless or with legs torn off, some literally cut in two. Such were the Secesh who had been killed by our artillery, while our men had been killed or wounded early in the day by musket balls. Colonel Rogers was found dead, lying against a tree in his stocking feet, some vandal having pulled off and appropriated his boots. I saw some dead Negroes who had apparently been fighting on the Rebel side. Dead and wounded were scattered all about the field for a couple of miles.

I was glad to get orders that night to join my regiment and at 3 o’clock the next morning, the whole army started by different roads in pursuit of the retreating foe. We left everything behind in the shape of baggage; the men had neither tents or blankets. My baggage consisted of an overcoat and blanket strapped behind the saddle. We were victorious and after a flying enemy and cared little for inconvenience. For the first two miles of our march, we were going over the battlefield of the previous two days. A young surgeon and myself would at times ride into the woods and at every few steps, our horses would snort at the dead body of a Secesh soldier. Splintered trees, fragments of shells, torn and bloody clothing were evidence of a hard-fought battle.

Good article Dan.

ReplyDelete