“Give it to ‘em boys, you’re cutting them all to hell!” The 14th Ohio Battery at Shiloh

The

14th

Ohio Battery was recruited by Captain Jerome Bonaparte Burrows of

Geneva, Ohio from the northeastern counties of Ashtabula, Geauga,

Lake, and Trumbull, mustering into service September 10, 1861 at Camp

Cleveland. The battery trained in Cleveland for several months before

heading south in January 1862. Originally destined for duty out west

with the 2nd

Ohio Cavalry, it reached St. Louis where General Halleck elected to

keep the battery for operations in Tennessee. The battery arrived at

Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee on March 14, 1862 and went into camp.

|

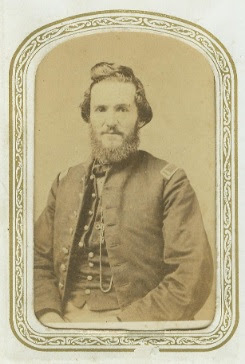

| First Lt. Homer H. Stull, 14th Ohio Battery Photo from Find-A Grave courtesy of Rick Lawrence |

Homer

H. Stull of Trumbull County, Ohio was appointed a First Lieutenant in

the battery on September 10, 1861 and wrote a series of ten letters

to his hometown newspaper The

Western Reserve Chronicle

describing the services of Burrows’ Battery. His brother John was a

resident of Warren, Ohio and friend of the editor of the newspaper.

The following account, written under the pen name “Bernum” and

supplemented by accounts from other members of the battery, was

published on page two of the April 30, 1862 issue of that newspaper.

Lieutenant Stull died of bilious fever on the morning May 17, 1863 at

Jackson, Tennessee. The newspaper was quickly apprised of his decease

and lauded the lieutenant as “one of the truest and most faithful

soldiers that drew a sword in defense of the Union cause. He was

idolized by the men of the 14th

Battery.” (Western

Reserve Chronicle,

May 20, 1863, pg. 3) The June 3, 1863 issue of the Western

Reserve Chronicle

contained a tribute from the members of the 14th

Ohio Battery in which they praised Lieutenant Stull as a

“warm-hearted, kind, and steadfast friend” and one of the

brightest ornaments of the artillery service. He was buried at

Hillside Cemetery in West Farmington, Trumbull Co., Ohio with a stone

was erected in his memory by comrades of the 14th

Ohio Battery. [Photo of Lieutenant Stull courtesy of Rick Lawrence

and posted at Find-A-Grave.

|

| The 14th Ohio Battery was recruited from the northeastern corner of the state. |

The

14th

Ohio Battery was attached to Brigadier General John A. McClernand’s

division, but was not assigned to a specific brigade. The 95-man

battery under the command of Captain Burrows (also known as Burrows’

Battery) possessed four 6-lb Wiard rifles and two 12-lb Wiard

smoothbores and suffered casualties of 4 killed and 25 wounded along

with 70 of the battery’s horses cut down. All six cannon were

captured by the Confederates who overnight spiked the guns by

knocking off the sights and cutting the wheels. The Wiard cannon were

unusual artillery pieces in Federal service; the steel

(puddle-wrought iron) tubes were cast at O’Donnell’s Foundry in

New York City and placed upon a specially-designed carriage built by

Norman Wiard. The rifles had a range of about 7,000 yards firing a

6-lb Hotchkiss shell.

Pittsburgh

Landing, Tennessee

April

11, 1862

About

dusk on Friday a continuous roll of musketry, alternating with the

thunderous boom of cannon, announced an attack upon our right wing.

The long roll, the alarm cry of war, sounded through the camp giving

intelligence that help was needed with the rapidity of a Highland

watch fire. Throughout the two divisions thus summoned to the fray,

the soldiers instantly fell into the line and were speedily on the

double quick to the scene of action. Of our battery I need only say

that although in the second line of encampments, it was one of the

first in the field. Fully 15,000 men were soon on the spot but only

to find that the enemy had been repulsed by Sherman’s division

alone. I allude to this incident here to show lack of caution

exhibited two days subsequently when the foe was permitted to

approach within a mile of our lines before being engaged and would

add that from the zeal and enthusiasm then displayed by the men of

the 14th

Ohio Battery, I had not a doubt of their valor when the time for its

exhibition should come. In 36 hours that time arrived and nobly did

these gallant spirits fulfill the hopes their zeal excited.

Sunday

morning before breakfast, the action commenced on our right wing but

the success of Friday evening’s skirmish made our men underrate the

valor and strength of the Rebels and it was not until borne down by

vastly superior numbers, that the long roll was again sounded. Then

there was “mustering in hot haste” and soon all went pouring

forward in the “impetuous tide of war.” Our battery having taken

their position in McClernand’s Division the day previous, we were

in the front line of camps and at the first summons formed in good

order while fragments of shell were whizzing through the trees above

their heads. In a few minutes we were speeding at a gallop to the

scene of strife, first taking a position within hundreds of rods of

our quarters at the edge of a wood. The third section, embracing two

pieces under the command of Lieutenant [Walter B.] King (acting in

the absence of Lieutenant [William H.] Smith) was ordered forward and

took position at a crossing of two roads to protect them and subject

the enemy to a raking fire on their approach. [This would be the

intersection of the Hamburg-Purdy road running east to west and the

Corinth Road running north to south.] From here the line of fire

could be distinctly seen and wounded men were constantly filing by on

their way to camp, while those unable to help themselves were being

carried past by their comrades on muskets and rude litters.

Soon

the remaining pieces were ordered up and the whole battery commanded

to move to the line of fire and then took position in the woods to

our left. Our captain is said to have replied to this order “That

is not my place. I cannot hold my guns there half an hour. My boys

will be all cut to pieces.” There was not time for parley, however,

and we immediately took the place assigned us, a most unfortunate

position where we could not even see the enemy at a distance of 50

rods who, true to their treasonable instincts, advanced under the

American colors. The 12th

Iowa and 14th

Illinois, our supporting infantry, took position in our rear to the

right and left respectively so that from the first we bore the brunt

of the fire. [Ohio

at Shiloh

states that the 14th

Ohio Battery was supported on its right by the 11th

Illinois of Colonel C. Carroll Marsh’s brigade of McClernand’s

division. Stull was correct that he was supported on the left by an

Iowa regiment but had the number wrong- the 12th

Iowa was part of Colonel James M. Tuttle’s brigade of General

W.H.L. Wallace’s division and fought in the Hornet’s Nest located

quite a distance to the east. The 11th

Iowa from Colonel Abraham Hare’s brigade was detached from the

brigade and lay on the battery’s left. The 14th

Illinois was part of Colonel James C. Veatch’s brigade of General

Stephen Hurlbut’s division and covered the retreat of the battery

at 11 A.M. Maps that I consulted are not in agreement as to all of

this so I’d offer this as my interpretation. The regimental

identifications in Stull’s letter could also be mixed up due to a

simple newspaper compositor’s error.]

The

treachery of the Rebels aided by the color of their clothing, which

was the exact hue of the dead leaves covering the ground, enabled

them to advance and deliver a telling fire before we were certain of

their identity.

The

Illinois regiment [48th

Illinois] on our left who, from their position, could see the effects

of our fire better than ourselves by reason of the dense smoke would

cry out by way of encouragement “Give it to ‘em boys, you’re

cutting them all to hell!” The Rebel forces swept nearer and nearer

till some of our men heard one of them say distinctly “By God,

here’s a battery that has no infantry that we can take as well as

not,” and suiting the action to the word, they bore down upon our

unprotected right, by a flank movement, to contend against which

would have been certain destruction. We made a precipitate retreat to

the quarters we had left scarce an hour before, leaving four dead and

five wounded upon the field and one-fourth of the command disabled by

wounds, nearly 20 of whom we got off with us besides securing six

caissons and two limbers. [The battery was captured by the troops of

16th

Alabama and 27th

Tennessee regiments of General Sterling A.M. Wood’s brigade of

Hardee’s Corps. General Wood commented in his report that the

battery was taken only “with great loss on our side.” Among the

casualties was Colonel Christopher Harris “Kit” Williams of the

27th

Tennessee was struck in the chest by a bullet and killed while

charging Burrow’s battery. General McClernand in his official

report noted that “the underbrush and trees bear abundant and

impressive evidence of the sanguinary character of this engagement.”]

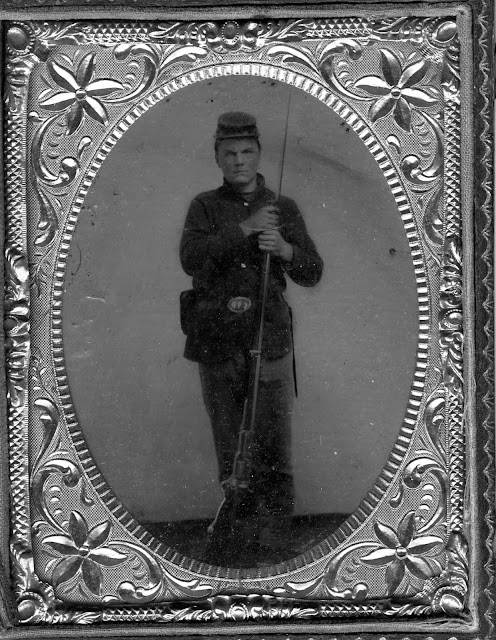

|

| Captain Jerome B. Burrows 14th Ohio Battery |

Of

the wounded I will briefly mention that Captain Jerome Burrows was

shot by a musket ball near the right elbow while standing between

Lieutenant King and Ellsworth on the right flank. [Private George

Ellsworth, a relative of Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, had been assigned

to the battery just a week before from the ranks of the 28th

Iowa Infantry.] It was a severe wound and it was feared for a time

that he might lose his arm. John S. Hunter, James S. Reed, Lucius C.

Waters, and William C. Hall were left on the field and that night

lodged in Rebel hands who, to their honor be it said, treated them

tenderly and kindly. [Reed would die of his wounds May 26, 1862 and

Hall would die of his wounds May 8, 1862 at St. Louis, Missouri.

Lucius Waters was discharged at the end of April 1862 due to the

severity of his wounds.] They heard the Rebels swear terribly about

the execution of our battery which they proceeded to spike and

dismount at once in which condition we found it but, thanks to our

artificers Thomas Douglas, Wilson S. Hamilton, and Philo Maltby, our

steel dogs can now bite as well as bark. With less than 70 men left

of the 95 who went into that fatal field we eagerly await the command

to again let slip those dogs of war.

Of

the battle I only pause to say that on Sunday, many regiments went

into the field without orders or a head. Sunday evening saw our

forces badly beaten, having been driven almost helplessly two miles

to the river, leaving almost every camp with vast stores in Rebel

possession for nearly 24 hours and themselves penned into a few

hundred acres all that night like so many sheep for the slaughter.

Had the shelling commenced by the enemy been kept up two hours we

would have been completely at their mercy. Nothing but a single

battery of siege guns on our left wing with the aid of a gunboat and

the coming on of night prevented a disgraceful surrender or total

annihilation.

General

Grant is reported to have held a white flag furled about its staff

for two hours ready to display it had the Rebel shelling continued.

How true this rumor is I know not and trust it is an idle tale. That

thousands hoped so I am confident and that a panic great, pervading,

and ignominious prevailed, I was an eyewitness to it, and saw fully

5,000 seeking shelter behind the river bluffs or on the boats from

which they were only kept back by bayonets presented at a charge on

every gangway plank. Others attempted to swim the river and many are

reported to have lost their worthless lives in the attempt. Buell’s

reinforcements poured in that evening and the next day. Real

generalship was now displayed. The Rebel lines were driven back till

3 P.M. and they lost all the ground they had won and fell back in

utter confusion. The valor of Ohio troops alone saved the day and

turned the tide of battle.

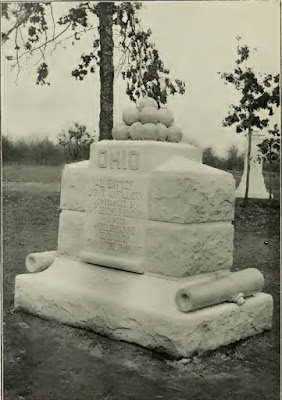

|

| 14th Ohio Battery Monument at Shiloh |

Private Richard V. Taylor of Leroy, Ohio was badly wounded through both arms and was discharged for wounds at the end of April 1862. He passed through Cleveland in mid-April and relayed the following to the reporter from the Cleveland Plain Dealer. “Taylor says that he was on his way to a spring for the purpose of getting some water when he heard the report of musketry and artillery and he remarked to his comrades that they would have fighting enough to do this day.” [There was a creek located just west of the Corinth Road in the vicinity of McClernand’s camp.]

‘A few moments after we heard a hissing sound overhead and looking up saw an old shell coming through the air. It hit on the side of a tree above our heads but didn’t burst. From the tree it glanced off and hit one of our horses wounding him. He broke away and ran. The report of firearms now came nearer and we received ordered to harness up and get ready for action. We did so and took a position in a clump of woods. We soon saw the enemy coming over the hill and firing on as they came. We had six or eight men killed and Captain Burrows was wounded above the right elbow, the ball coming our below. He was conveyed on board one of the vessels near. All the horses on the caissons were killed.’

“Taylor said the battery was placed in such a condition from the loss of men and horses that it was temporarily broken up- the men volunteering in other batteries during the battle. It is impossible to view the bullet-riddled garments of these volunteers without having a vivid perception of the hotness of the fire poured in upon our troops on that fatal Sunday morning.” The reporter stated that Taylor’s wounds hadn’t been dressed in three days “and they were consequently in bad condition, as the odor emitted from them plainly testified.” (“War Items from the Battlefield, Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 18, 1862, pg. 3)

| The desperate fighting for possession of the 14th Ohio Battery came at great cost to the Confederates. |

Private Elmer Bacon moved to Streator, Illinois after the war and provided the following account to the chroniclers of the Soldiers’ and Patriots’ Biographical Album which was published by the Union Veteran Publishing Co. in 1892- this is a tremendous and relatively untapped source for battle accounts which can be found here:

“Early on April 6, Mr. Bacon’s battery bravely responded to the bugle’s call, was placed in position, and had their guns leveled when they descried a body of men approaching, but orders were given not to fire as it was supposed they were Union troops. Corporal George Tracy of Mr. Bacon’s detachment was on the ground and concluded it was the enemy, whereupon the order was given to fire. This battery was one of the first that opened fire on the enemy in that sanguinary battle. The battery fired rapidly until enveloped in a cloud of smoke, completely obscuring both the enemy and the battery. Mr. Bacon, in attempting to load his gun, found himself without ammunition and none forthcoming. The gunner hastily ran back to discover the cause of the delay and not returning, Mr. Bacon himself started for the same purpose and soon discovered the cause. Their captain and 28 men had been either killed or wounded and upwards of 70 horses disabled. Their guns were captured but none of the men except the wounded fell into the hands of the enemy. Mr. Bacon escaped with one of the limbers and the men operating at the guns and a portion of the team, and did no further service in that battle as their guns and outfit had been captured. On the following Monday, they recovered their guns but they were spiked. The battery remained on the battlefield for some days where it was refitted and about 50 men from the 13th Ohio Battery assigned to duty with it and so remained during the war.” [The 13th Ohio Battery was disbanded due to poor battlefield performance on April 6th.]

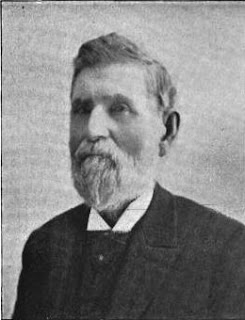

|

| General Sterling A.M. Wood, C.S.A. Troops from his brigade captured the 14th Ohio Battery at Shiloh. |

Two regiments were ordered to support our battery on our right and left respectively. The battery was stationed on a ridge, ranging across a ravine, and to the right of us about twelve rods, was another ridge. We had no sooner got into position that the order was given to load. The rebels were seen in the bushes bearing the American flag. We were deceived only for a moment, and gave them a salute with shell from our guns. The balls now began whistling about us like hail, but our guns were served with rapidity and accuracy, doing fearful damage to the enemy. We kept them at bay in front, but a large force came up sheltered by the ridge on our right, and the infantry fell back, leaving us entirely unsupported. Our battery was flanked, and exposed to a raking fire, but we still stood by our guns, and the gun of our detachment cut down the rebel flag, killing the color bearer. Captain Burrows had been shot through the arm and borne off the field, a large portion of the men killed and wounded, and the order was given, “Limber to the rear.” The horses were brought round, but in less time than I can write it, many of them were shot down, and our battery was lost. We got off the field, what was left of us, God only knows how. I never expect to face so great danger again if I should be in a hundred battles.”

Private Charles E. Austin provided the following account to the Ashtabula Sentinel, which was reprinted in the Ashtabula Weekly Telegraph: “Our guns are all gone. We were ordered to take such a position and hold it, and we did so as long as we could, and would have done so until this time, if our support had not run. The regiments on our right and left supporting us, did not fire two hundred shots from both regiments; but as soon as the enemy were in musket range, they ran like dogs, and we stood at our guns receiving the whole fire of the enemy, who tried to silence our guns. We were ordered to limber to the rear, the rebels were not over sixty yards off, and before we could get our gun limbered, five of our six horses were killed and the sixth wounded. The order came to leave our gun, when we fired the load we had it at the devils. At that time I was hit on the head and knocked down. Daniel Simms started to put down another load, but Sergeant Frederick B. Pierce made him leave. Our boys behaved like veterans; not a man left until he was ordered. Number Six gun fired the last shot, and the Rebels were not over thirty yards off when we left. Our guns are retaken [the next day], but were dismounted and spiked, and the wheels knocked to pieces.” (Ashtabula Weekly Telegraph, April 26, 1862, pg. 3)]

|

| This depiction of Captain Andrew Hickenlooper's 5th Ohio Battery at Shiloh gives some indication of the confusion and chaos of Civil War battlefields. |

For

more reading on the service of the 14th

Ohio Battery, please check out William Griffings’ superb letter

collection of Captain Jerome Burrows which is here.

Comments

Post a Comment