Standing like pillars of adamant: the 61st Ohio at Freeman's Ford

The

Battle of Freeman’s Ford, Virginia was fought August 22, 1862 along

the banks of the Rappahannock River in one of the opening thrusts of

the campaign which culminated with the Second Battle of Bull Run.

Stonewall Jackson was busily working his way along the south bank of

the Rappahannock in an attempt to get around the right flank of

General John Pope’s Army of Virginia when scouts reported the

movement to General Franz Sigel. Sigel directed divisional commander

Carl Schurz to reconnoiter across the river to determine the enemy’s

strength, and if possible, to disrupt the movement of Confederate

forces.

|

| Major General Carl Schurz |

“I

selected Colonel Schimmelpfennig’s 74th

Pennsylvania,” wrote General Schurz. “Schimmelpfennig forthwith

forded the river, the water reaching up to the belts of the men,

ascended the rising open field on the other side, crossed a belt of

timber on top of it and saw a large wagon train of the enemy moving

northward apparently unguarded. He promptly captured eleven

heavily-loaded pack mules and several infantrymen, and also observed

troops marching not far off. His booty he sent to me, with the

request that the other two regiments of the brigade be thrown across

to support him if he were to do anything further, and to secure his

retreat in case the enemy should try to get between him and the

river.”

Schurz

had the two remaining regiments of General Henry Bohlen’s brigade

at hand at Freeman’s Ford (the 8th

West Virginia and 61st

Ohio) and sent them over to reinforce Schimmelpfennig’s line.

“Although in the regular order of things I was not required as

commander of the division to accompany the brigade in person, I

followed an instinctive impulse to do so, this being my first

opportunity to be with the troops of my command under fire. I placed

a mountain howitzer battery on an eminence to sweep the open field

and the roads on the other side in case of necessity and then I

crossed with some members of my staff,” wrote Schurz.

Earlier

that morning, General Schurz had honored the 61st

Ohio by presenting the regiment with the divisional colors. “While

yet four miles distant from the battleground, General Schurz

presented the 61st

Ohio with his divisional colors and said he hoped we would do them

honor,” remembered Private Samuel Rau of Company D. “We proudly

took them, and gave three hearty cheers as the ample folds of the

good old flag were unfurled over our heads.” Colonel Newton

Schleich entrusted the colors to Sergeant William Kirkwood of Company

C. “The Colonel called for me and told me that he assigned to me

the part of honor, and that I must never let these colors fall,”

wrote Kirkwood. “I promised him they never should until I fell with

them. The Colonel then called on the boys to never disgrace him,

their regiment, or their colors.” The regiment soon had ample

opportunity to win their laurels.

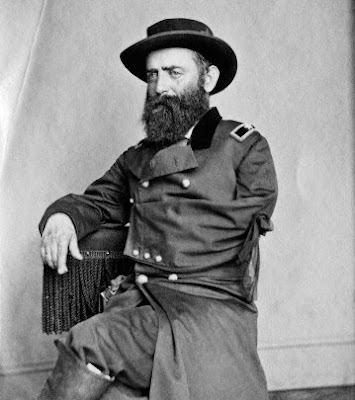

|

| Colonel Newton Schleich, 61st OVI |

Private

Rau continues the story. “The Rappahannock is fordable at this

point. We were however obliged to wade through the water and mud

almost waist deep and protected our guns and ammunitions from the wet

by holding them at arms’ length and over our heads. After emerging

from the water we were obliged to climb a steep, shrub-covered

embankment in order to gain the level meadow above. Upon gaining the

level space beyond the river, we formed into platoons and slowly

proceeded to the edge of a wood on a gently sloping hill and halted.”

Crossing

the Rappahannock at the head of its regiment as it entered its first

fight, Colonel Schleich soon disappeared. Lieutenant Colonel Stephen

J. McGroarty reported that the colonel, “shortly after the opening

of the fight, could not be found, and the regiment, being without a

head, was led on by Captain Koenig of General Schurz’s staff and

myself.” Colonel Schleich was not alone; several weeks later

McGroarty reported in his official after action report of the

campaign that the colonel and seven lieutenants were also

“unaccountably absent since the skirmish at Freeman’s Ford. I

hope, general, that you will find it convenient to inquire into the

reason of the absence and general conduct of the named officers.”

General Schimmelpfenning did so inquire, and by mid-October 1862,

Schleich and all seven lieutenants had either been discharged or had

resigned their commissions.

|

| Colonel (later Brigadier General) Alexander Schimmelpfennig, 74th Pennsylvania Infantry |

While

some of the officers sloughed off into the brush, the remainder of

the regiment stood their ground. Private Rau wrote that “we were

only a few minutes in the woods until our skirmishers commenced a

brisk fire, and soon after were forced to fall back upon us for

support. The enemy at first tried to draw us into an ambush, but

finding that General Sigel would not bite at the bait, set in upon us

with the ferocity of devils incarnate.”

“Colonel

Schimmelpfennig’s foresight in asking for help proved well

founded,” averred General Schurz. “When he proceeded to subject

the Rebel wagon train to further annoyance, Trimble’s brigade of

Stonewall Jackson’s rear guard suddenly turned about and fell on

our right flank, and the two regiments brought to Schimmelpfennig’s

aid were at once hotly engaged.” Private Joseph C. Lowe of Co. C of

the 61st

Ohio stated that the skirmishers “had been out but a few moments

when firing became general between them and the enemy, and in less

time than I am taking to describe the scene which occurred, the

skirmishers came rushing in, firing as they ran, hotly pursued by

more than ten times their number. We no sooner discovered this than a

line of battle was formed by our brigade in front of the woods on the

south side, while the enemy was steadily advancing in front with

several whole brigades, firing into our ranks as they advanced, and

we, standing like pillars of adamant, not daring to fire for fear of

cutting down our own men (the skirmishers) between us and the enemy.

No sooner had the skirmishers entered within our own lines than we

discharged a volley into the enemy’s ranks and fell back a few

steps to the edge of the woods and loaded, preparatory to a second

volley, when the 8th

West Virginia and 74th

Pennsylvania retreated.”

Schurz

reported that the Confederate assault “was fierce, and my 8th

West Virginia broke and ran. My first service on the battlefield thus

consisted in stopping and rallying broken troops, which I and my

staff officers did with drawn swords and lively language.” (Schurz

would unfortunately gain much experience in this activity, being with

the 11th

Corps at both Chancellorsville and Gettysburg). The men of the 61st

Ohio watched in disbelief as first their skirmishers then entire

regiments started to bolt from the field. “The Rebels came out in

swarms, the 8th

West Virginia ran and never rallied until they got across the river,

and the 74th

Pennsylvania ran right through our line of battle but we stood our

ground like men,” wrote Sergeant Kirkwood with understandable

pride.

The

61st

Ohio was soon hemmed in by Confederate infantry in their front and on

both flanks. Private Lowe wrote that “the third time our boys

rallied and discharged another volley, when another brigade was

discovered on our right flank, firing into our ranks as they

advanced. Thus we were almost entirely hemmed in, the enemy being in

front and on the right and left flank, and a muddy dirty river in our

rear. As soon as this was discovered, we were ordered to fall back;

the flight and the pursuit then became general. Our men ran down the

hill and plunged into the river at whatever point they happened first

to make, some swimming, others running the best way they could, and

others trudging through the mud, the enemy’s balls falling in the

river and on the opposite bank for which our troops were making, like

hail in a violent storm. It is certainly providential and appears

almost miraculous that so many of us escaped.”

|

| Battle of Freeman's Ford |

Sergeant

Kirkwood was wounded twice while retreating toward the ford. “I was

hit across the head and fell; I gathered myself up and was then

struck across the knee cap which came near knocking it off. The

colonel then ordered me to be taken to the rear; as I was leaving,

they made the third and last rally. I gave the flag to a brave little

corporal on my right as I left but he was soon knocked over, but

another one of the color guards picked up the flag and brought it

across the river safe.”

“The

‘butternut devils’ fought with desperation,” commented Private

Rau who was wounded in the leg during the retreat. “Many of them

were without coats or hats and look it ala-Bull Run. They pursued us

to the water’s edge and many of our brave fellows perished in the

river, being obliged to cross below the ferry where the water was too

deep to be waded, and where the enemy was playing with musketry. The

engagement lasted about an hour, but was most terrific for the

numbers engaged.”

Sergeant

Kirkwood witnessed the death of General Bohlen along the river bank.

“As I was leaving the field, our general (Henry Bohlen) was shot

within 30 feet of me and his horse came near running over the boys

that were helping me from the field. Lieutenant Milton W. Junkins,

who is a brave little fellow, was knocked down the bank of the river

by a smearcase Dutchman belonging to the 74th

Pennsylvania; (this regiment had) rallied on the river bank and were

pouring a galling fire into our regiment as we were retreating down

the hill.” Private Rau also witnessed the death of General Bohlen,

stating that “as he fell, he exclaimed, ‘Boys, I am dead, but go

on and fight!”

“Many

of us were saved by the timely energy of Schenk’s and Milroy’s

men on this side of the river who, as soon as our men were supposed

to have arrived, covered our retreat by a galling fire upon the enemy

who had followed us to the water’s edge,” wrote Private Lowe. “I

myself had plunged in the river at the first place I came and after

swimming perhaps some 20 feet found that my haversack, canteen,

cartridge box with 50 rounds, and heavy clothing were weighing me

down in deep water, when I made my way back to the shore, and laid

there in the mud under the bank until the fire on both sides, which

continued for the space of half an hour over my head, had ceased, and

the enemy had retreated.”

General

Schurz stated that “when our regiments were out of the woods, they

went down the field to the river at a somewhat accelerated pace.

Forthwith our artillery opened to keep the enemy from venturing into

the open, but they pushed a skirmish line to the edge of the woods to

send their musket balls after us. General Bohlen fell dead from his

horse, shot through the heart. I thought it would not do for the

division commander and his staff officers to retreat in full view of

his command at a gait faster than a walk. So we moved down to the

river in a leisurely way. I did not cross the ford until my regiments

were all on the other side. When I rode up the bank, the brigade

drawn up there in line received me with a ringing cheer. I met

General Sigel, who watched the whole operation. His first word was

“Where is your hat?” I answered, “It must be somewhere in the

woods yonder. Whether it was knocked from my head by a Rebel bullet

or the branch of a tree, I don’t know. But let us say a Rebel

bullet. It sounds better.” We had a merry laugh. “Well,” said

Sigel, “I am glad you are here again. When I saw you coming down

that field at a walk under the fire from the woods, I feared to see

you drop at any moment.”

|

| Corps commander Franz Sigel met General Schurz and his staff after they retreated safely across the Rappahannock. His first words to Schurz were "Where is your hat?" |

“This

Freeman’s Ford fight amounted to very little as it was,” wrote

Schurz. “But it might have been of importance had it been followed

up by a vigorous push of our forces assembled at and near Freeman’s

Ford to break into the Rebel column of march just at the point where

Jackson’s wagon train passed along and only his rearguard and

Longstreet’s vanguard were within supporting distance.”

That

evening, Private Rau was loaded in an ambulance and set out for

Washington. “Late in the evening of the day of battle, we left for

Rappahannock Station with sixteen ambulances full of wounded, and

from thence on Saturday morning for Alexandria, where we arrived at 4

o’clock Sunday morning. Washington and Alexandria are literally

filled with sick and wounded. Private houses, churches, and even

parts of the Capitol building are being converted into hospitals.

Everything is excitement and bustle.”

Freeman’s

Ford was a battle of beginnings and endings for both the 61st

Ohio and for General Carl Schurz. For the regiment and the general,

it was the first exposure to the rigors of combat, and both would see

much more of it before the war would come to a close. The 61st

Ohio gained a reputation for its steadiness under fire at Freeman’s

Ford. Whitelaw Reid wrote that the 61st

Ohio “was always a reliable regiment and was ever found where duty

called it. Its losses by the casualties of the field were so numerous

that at the close of its service a little band of only about 60 men

and officers remained to answer it last roll call.” Sergeant

Kirkwood offered that Freeman’s Ford “will never be forgotten by

any of us, for we may get into 50 fights before we get through and

never get into as hot a place as we did that day.”

|

| Lieutenant Colonel Stephen J. McGroarty led the 61st Ohio at Freeman's Ford after Colonel Schleich went "unaccountably absent." He would lead the regiment for the rest of the war. |

But

the battle also proved to be the beginning of the end of Colonel

Newton Schleich. He rode across the Rappanhannock with the regiment

into the engagement but then unaccountably disappeared for the

remainder of the battle, and for several days afterwards could not be

found. Having charged Sergeant Kirkwood with never disgracing the

regiment, Schleich’s actions during and after the battle became

subject to wide comment with the opinions being that Schleich was

either a drunk or a coward.

In

his post entitled “A Tremendous Little Man” featured on Emerging

Civil War on August 30th

of this year (see here). Jon-Erik Gilot opined that Schleich was “arguably one of the worst

political generals produced by the state of Ohio during the Civil

War” and it is hard to disagree with that assessment. With rumors

swirling that he had been either drunk or a coward at Freeman’s

Ford (as well as charges of negligence and outright desertion) and

finding his regiment again under the command of his old nemesis

George B. McClellan, Schleich offered his resignation on September

20, 1862 which was accepted a few days later.

|

| Letter from a member of Co. B, 74th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry published in the September 9, 1862 issue of the Pittsburgher Volksblatt describing the fight at Freeman's Ford. |

Comments

Post a Comment