Wiards of Ohio

At

the outbreak of the Civil War, Norman K. Wiard had a reputation as a bit of a

quack, his most recent and notable achievement was the development of an “locomotive

vehicle for running on ice or water” (Patent #26290A) dubbed by the Chicago Tribune the “ice boat.” The boat had not proven a

success, but with hostilities with the Confederacy now a reality, Wiard turned

his creative genius to revolutionizing the U.S. Army’s moribund Ordnance

Department. “I found on examination of the field artillery used in the United

States service that there was no less than nine different calibers of

rifle and smoothbore guns adopted and in use, and that nothing like system or

uniformity prevailed in the department,” he commented in a pamphlet published

in 1863. “I found also that the variety and size of the projectiles were even

more numerous than the calibers of the guns,” and that the head of the

department, General James W. Ripley, had no desire change things.

“Impressed by these facts and knowing

the needs of the country, I commenced an investigation shortly after the fall

of Fort Sumter which resulted in the design and production of a system of field

artillery,” the Janesville, Wisconsin man stated. “I have met with the most determined

hostility and opposition both from General Ripley and from General [William F.]

Barry, chief of the Army Ordnance, who opposed the introduction of any guns but

the Parrott cast-iron guns with their clumsy projectiles which were the pets of

General Barry, and the 3”wrought-iron ordnance gun, the only one designed and

offered by the Army Ordnance Department.” Wiard found much to criticize in the

Army’s selection of shells, lambasting the Dyer projectile (“utterly worthless”)

and the Schenkl and Parrott shells (“worthless”) and commented that the “last

appearance of the Schenkl projectile was at Fredericksburg” where “over 30,000

of them were on hand and although General Ripley knew them to be literally

worthless, as not one in 20 would take rifling, he suffered many thousands to

forward to the army which were afterwards fired in Fredericksburg but without

any very serious destructive effect.”

Wiard set to work in his New York

shops to develop better cannon for the U.S. Army, and developed both a 6-lb

rifled gun and a 12-lb rifled gun. Wiard focused his attention on the design of

the carriage as well as the actual gun tube. To minimize recoil, he designed the

breech end of the gun with a very bulbous appearance, and thinned out the

barrel past the trunnion. His primary innovation with the carriage was to place

the axle below the gun carriage which allowed for not only a stronger carriage

(and one much less prone to breaking when firing) but also the ability to

elevate the gun to 36 degrees, greatly extending its range. “The breech is rounded and without ridge or

ring, thus securing an equal and safe expansion of the metal when heated. The

diameter of the breech is ten inches and bore about 48 inches,” reported the Chicago

Tribune. The cannon featured “gain twist” rifling with about eight grooves

and eight lands and had fixed sights. “The cannon throws both round shot and shell

of a conical shape and also for the first time in rifled guns canister shot.

The wheels are built up by wedges and screws in such a manner than no shrinkage

of the wood can loosen the wheel.”

The

first test of Wiard’s new cannon came in July 1861 at West Point, New York

where Wiard guns, firing a Hotchkiss shell, “completely riddled” the target

place at 1,650 yards distance “every ball striking within an area of six feet

of the bullseye. Additional testing in Washington again showed the superiority

of Wiard’s design and he was given a contract for production. By late

September, Wiard had five shops running all out producing guns for the army. “He

has organized five distinct shops and stocked them with all the requisite

machinery,” wrote a Wisconsin visitor. “These shops are owned by different

parties though superintended by Wiard and employ 480 men. Mr. Wiard commenced

with steel ingots and finishes the gun ready for use. Five of the 12-lb guns

are completed each day.” O’Donnell’s Foundry in New York cast the pieces.

Wiard’s

first pieces were sent to the Navy which used them to arm various vessels, but

he also was sending cannon out West for use by General Fremont’s forces in

Missouri, several were also used by Ambrose Burnside’s troops in their North

Carolina coastal campaign. By January 1862, former Attorney General Christopher

Parsons Wolcott of Ohio had convinced the War Department to provide the state

with four batteries of Wiards to arm batteries about to enter the service. The

first guns arrived at Camp Dennison in mid-January and were quickly put through

their paces. “A muslin target was stretched on the hillside and every preparation

made for the experiments. By placing the trail under instead of over the axle,

the gun can be depressed or elevated some 36 degrees. Using but an ounce of

powder, shells were projected to the prodigious height of one mile and dropped

behind the target where they exploded in every instance. So slight was the

report that many spectators could not believe there had been an explosion of

the charge till they would hear the report of the shell exploding,” it was

reported. “The muslin was riddled with grape in a way calculated to make on

feel uncomfortable nor was there the least evidence after repeated trial that

the rifling of the gun had been in any respect injured. The precision of the

piece in firing was further demonstrated by two shells aimed at an elm tree, both

of which took effect and exploded in its massive trunk, tearing it into

smithereens.”

|

| Christopher P. Wolcott |

A

delegation of Ohio battery officers proclaimed that “no such effective weapon

has hitherto been seen in the West” and urged Governor David Tod to secure more

Wiards for Ohio. “We think that these guns answer all the requirements of a

field battery and we would therefore respectfully submit that the efficiency of

this arm of the service would be greatly increased if the Ohio artillery were

supplied with these guns in place of the rifled bronze guns now in use,” they

said. Among the signatories of this letter was Captain Jerome B. Burroughs in

command of the 14th Ohio Independent Battery; Burroughs became the

first battery to receive Wiards, being issued four 6-lb rifles and two 12-lb

rifles. The other Ohio batteries that received Wiards included Batteries G and

K of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery who received them in late January,

the 4th Ohio Independent Battery, and the 12th Ohio

Independent Battery which received them in May 1862.

Praise

for the Wiards was quick in coming. Battery G and the 14th Ohio

Battery both used them with deadly effect at Shiloh in April, Private George

Moore of Battery G commented that the 12-lb rifle he fired “did more execution

than any other gun on the field.” The 14th Ohio, despite being

overrun and all six pieces spiked by the Confederates, loved their Wiards and

rebuilt them as soon as recovered on the field the next day.

Wiards

went to the eastern theater as well where Captain Aaron C. Johnson of the 12th

Ohio Battery praised their toughness and accuracy. “I have fired the Wiard

battery nearly 3,000 times,” he wrote Norman Wiard in December 1862. “I moved

the Wiard battery from western Virginia in the campaign with General Milroy and

also through the entire campaign with General Fremont, also under General

Sigel, traveling about 600 miles and have not in all that time had an axle

break, nor a wheel give way either in marching or in firing. A more certain and

reliable aim can be taken with your sights than with any other that I know of,”

Johnson commented. “In fact, most of the artillery officers with whom I am acquainted

prefer a battery of Wiard guns to any other and I am sure no artillerist will

be satisfied with other guns after using yours.” Johnson’s battery was captured

at Second Bull Run and the Ordnance Department issued 3” Ordnance rifles as replacements,

a move which caused much dissatisfaction with the men who “are anxious to get

back the old battery.”

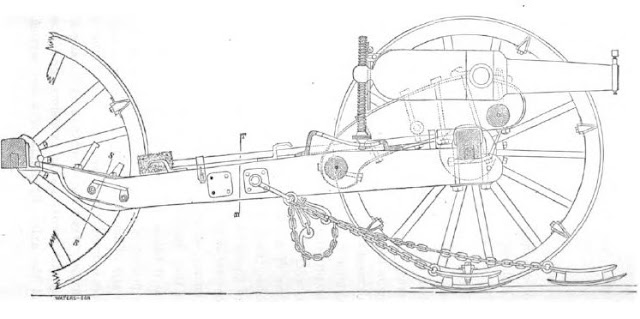

|

| Wiard diagram |

General Franz Siegel, an trained artillerist from his

days in the German army, also had high praise for the Wiards stated that the 12

Wiards in his corps “never failed me; none of the axles or others parts of

their carriages ever broke down, and their mobility, accuracy, and range,

together with the remarkable facility for adjustment and repair on the field,

were subject to general remark among officers and men. In my judgment, the

Wiard guns and equipments are superior to any field artillery I have ever seen

in service.”

Sources:

Wiard,

Norman L. Wiard’s System of Field Artillery as Improved to Meet the

Requirements of Modern Service. New York: Holman, 1863

“Government

Trial of Hotchkiss Projectiles,” New York Times, July 20, 1861

“The

Wiard Cannon,” Chicago Tribune, September 18, 1861, pg. 4

“Wiard’s

Manufactory of Steel Guns,” Wisconsin State Journal, October 2, 1861,

pg. 2

“Wiard’s

Steel Guns,” Cleveland Morning Leader, January 20, 1862, pg. 3

“From

Capt. Bartlett’s Battery,” Jeffersonian Democrat, April 25, 1862, pg. 3

Comments

Post a Comment