Retrieving Major Carpenter: Joseph R. Prentice Earns His Medal of Honor at Stones River

It was

midday on December 31, 1862, when the six companies constituting the 1st

Battalion of the 19th U.S. Infantry were thrust into the furnace in

the desperate fight to maintain control of the Nashville Pike at Stones River. “After

taking our position on the hill near the railroad, we were again ordered with

the remainder of the brigade to advance in line of battle into the cedars,”

recalled Captain James B. Mulligan. “We engaged an overwhelming force of the

enemy for a full 20 minutes. It was as we received the order to retire that our

Major Stephen D. Carpenter fell, receiving six mortal wounds and dying

instantly. The fire from the enemy at this time was terrific and our men were

falling on all sides.”

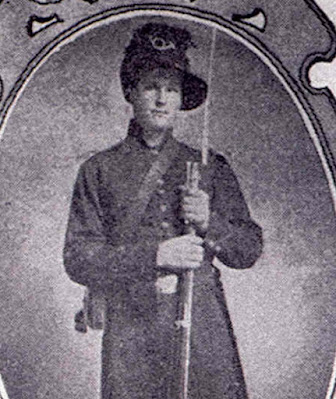

Private

Joseph R. Prentice of Co. E was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his

actions on the field that afternoon. “Our brigade was in the middle of the line

of attack and very soon the Rebels slackened their fire on our division and

concentrated all their energies upon the two wings of our line,” he wrote. “It

was evident that if the flanks were weakened, the enemy could very easily

surround us almost completely and so have us wholly at their mercy. To defeat

this plan, Major Carpenter ordered us to retreat in good order and after we had

about faced, he fell behind and proceeded to follow us in the rear. No sooner did

the enemy see us retreating than they opened fire on us again. I was in the

front rank in the advance, now in the rear in the retreat, and could plainly

see the awful destruction wrought upon our ranks by the death-dealing work of

the enemy. Suddenly, above the din and roar of battle, I heard the major call

our ‘Scatter and run boys!’ and was about to join the rest in the rush to a

place of safety when I heard a horse bearing down on me like mad. As I ran, I

looked around and saw that it was Major Carpenter’s horse dashing after us,

frenzied by several slight bullet wounds. I managed to turn him and head him

along our lines,” he wrote.

“Then I

rushed after the boys to tell them of the fate of the major but did not manage

to see any of the commanding officers until we retreated about a quarter of a

mile. Then I gained permission to return and look for him. Back I went at the

top of my speed and as soon as I entered the clearing, the enemy’s

sharpshooters opened a brisk fire on me. Still, I was bound to find the major

if possible and knowing about where he fell, rushed to the spot. Bullets

ploughed up little puffs of dust at my feet and whistled around my head. A

short spurt more and I was at the place. Glancing round, I saw him lying face

downward upon the dust and rushed to his assistance. But, poor fellow, he was

past need of human assistance! Nevertheless, I picked him up and carried him to

the rear, my ears filled with the mournful dirge of bullets that threatened me

at every step,” he stated.

The 19th

U.S. suffered greatly during the battle losing one seven men killed, 55 wounded

and seven missing during the fight on December 31st. “The only loss

of officers we sustained was Major Carpenter, a loss to this regiment which can

never be replaced,” noted Second Lieutenant Charles F. Miller of Co. E. “He was

a favorite with the old officers and a father to us young officers. During the

five days, we suffered much from fatigue, cold, and want of food. I saw our men

eat horse flesh and one day we had corn issued to us by the commissary one ear

to a man, the officers receiving the same.”

Long

after the war, Joseph Prentice recalled how he received the Medal of Honor for

his hometown newspaper the Hebron Journal of Hebron, Nebraska. “As Mr. Prentice

showed the medal, he remarked, “I would not take a farm for it.” The medal is

now kept in a frame but can be removed at the owner’s pleasure. The medal is

similar to a G.A.R. badge but is larger and has an additional emblem above the

flag. On the front of the star is a representation of liberty crushing

rebellion and on the other side is inscribed the following: ‘The Congress to

Joseph R. Prentice, late private, Co. E, 1st Battalion, 19th

U.S. Inf’y, for gallantry in action at the battle of Stone River, Tenn., Dec.

31, 1862.’ A manuscript letter also accompanied the medal signed by the

Adjutant General of the War Department.

“Our

brigade was in the battle of Stones River, Tennessee and was cut off from both sides

so that we had to retreat,” Prentice told the local reporter. “My major was cut

down and I returned and picked him up and his sword and carried him about one

half a mile. By the time I reached there, he was dead. The first lieutenant [Charles

Fleming Miller] noticed what I had done and made a memorandum of it for

promotion. Afterwards he went into recruiting service and I never got it. A few

years ago, I was reading about Andersonville prison and reading about these

medals of honor, I thought I would see if I couldn’t get one. I wrote to the

Adjutant General and he told me that my deed deserved a medal, and if I could

furnish proof of the facts, I could get it. I wrote to Colonel Anson McCook of

the 2nd Ohio and secured affidavits of five other soldiers who had witnessed

it and turned it over to the Adjutant General. Three of four years afterwards I

received the medal.”

Inscription on Joseph Prentice's gravestone in Hebron, Nebraska quotes the inscription on his Medal of Honor.

Sources:

Official

report of Captain James B. Mulligan, 19th U.S. Infantry

Account

of Private Joseph R. Prentice, Co. E, 19th U.S. Infantry, as written

in Beyer & Keydel’s Deeds of Valor, pgs. 127-128

“Medal

of Honor,” The Hebron Journal (Nebraska), February 15, 1895, pg. 5

Letter

from Second Lieutenant Charles Fleming Miller, Co. E, 19th U.S.

Infantry, Daily Capital City Fact (Ohio), January 23, 1863, pg. 2

Comments

Post a Comment