Hog Stealing with the 90th Ohio

Corporal

David C. Goodwin’s tale of stealing a hog then mouthing off to Colonel Charles Harker

gives an interesting insight into how many of the citizen soldiers struggled

with adapting to army discipline during the war.

It was October 1862 and the 90th Ohio was marching in pursuit of Braxton Bragg’s army into southeastern Kentucky. Goodwin was left behind and found himself scrounging for food when his rations gave out. (As an aside, the I think Goodwin changed the names of the officers involved as regimental rosters for the 65th Ohio show no Lt. Col. Young or Lt. Tunnahill.)

My story

begins at the foot of Wild Cat Mountain where I had my first ague chill. The

regiment was ordered to the salt works the next morning to destroy them. The

orders were that “all men not able to march 40 miles and back without rest must

go back to the wagon train” then in camp on Copper Creek close at hand. Our

good old Dr. Tipton gave me an excuse and two days’ rations and I went back,

finding Sylvester Rogers there on my arrival. He had nothing to eat but beans,

coffee, and salt. I divided up with him and we went it three days on my two

days’ rations and by that time we began to feel a vacancy in the region where

our stomachs used to be.

In those

days, the 90th was called a green regiment but we got just as hungry

if there was nothing to eat as a regiment that was ripe and ready to pull. So, Rogers

and I and our appetites held a council of war and the council resulted in an

order for fresh meat to season our coffee and beans with. I detailed myself to

hunt for a porker which I knew to be close at hand. There was an old Rebel who

lived in the big house on the hill nearby and the house had a porch in front.

Green recruit though I was, I had noticed a fine lot of porkers roosting under

that porch.

Harker’s

brigade of Wood’s division was camped all around that house and the tug of war

lay in how to get one of those pigs under the porch. I finally went up near the

porch and began picking up some old boards as if to make a fire and by some

means or other just at that time the hogs under the porch got scared and

started for the woods. I kept in sight of them with my kindlings until they got

through the camp, then I dropped the wood and got ready for business. The pigs

were driven up on the side of the mountain and I got a fine one.

|

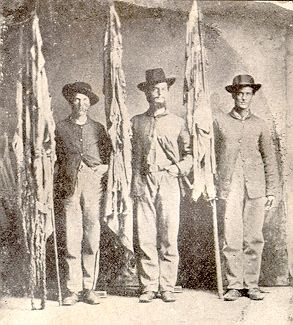

| The three color bearers of the 90th Ohio at the end of the war with David C. Goodwin standing at center. |

By some

unexplainable coincidence, Rogers was soon on hand with a mule and a couple of

corn sacks and we soon had our forage in camp. We had unfortunately left head

and hide on the spot and some of the 65th Ohio coming along and

observing the relics reported the matter to the old Rebel; he in turn reported

to Colonel Young of the 65th Ohio. He sent out a guard to hunt for

the hog and the guard found the hog cooking in our camp kettle. The colonel

wanted to take the hog but Rogers said, “No, that is our meat and when it is cooked,

we’ll look after that part of the program.”

“Who is

we,” asked the colonel.

“Rogers

and I,” I said.

“Then I

have got you,” the colonel said.

“And we’ve

got the hog,” said Rogers.

We were

promptly marched to Harker’s headquarters where for the first time we came in

contact with regular army officers. The General [Harker] was standing in his

tent door, the guard reported, and the General said, “Well you have got a

couple of hog thieves.”

Sitting

down on a large stone in front of his tent, he turned to us and commanded, “Attention!”

When we failed to come to that position, he repeated his command when I simply

said, “Talk away, we are listening.” And when in answer to his question we told

him we belonged to the 90th Ohio, he said, “You green troops it

appears to me came for no other purpose than to plunder and steal. What did you

come out for anyway?”

“We came out to fight for our

country,” said I “and we’re not going to starve doing it if we can find plenty

of hogs.”

“Don’t

you dare talk back to me,” said he.

“Don’t

ask us questions if you don’t want them answered,” said we.

“They

don’t know anything. Take them to the guardhouse,” Harker said.

“We know

a fat hog when we see it,” we responded as the guard took us out of his

presence. We were taken to the guardhouse and chucked in with ten or a dozen of

the 65th. We lay around until noon getting acquainted with the boys

when we were marched back to the wagon train to look after our pork which the

teamsters had finished cooking.

Our good

old friend Colonel Young came over from headquarters and made it his business

to propose to divide the pork for us. But we respectfully informed him that as

we were paying for that hog, we’d do the dividing ourselves.

The wagon

train moved that afternoon and we laid our plans to get away from the guards.

Our plan was to get a guard to go with us to the creek to wash. To get to the

creek, we had to pass through the wagon train. I was to make the break and wait

for Rogers at the top of the mountain. I got away all right and waited for Rogers

at the proper place, but he failed to put in his appearance. After waiting a

long while, I made up my mind to go back to Rogers at the foot of the mountain

for I knew he had not gotten away from the guard.

Just

then the officer of the guard passed me and in reply to my question as to

whether he lost anything or not, he said, “Yes, one of those infernal 90th

prisoners has run off and I’m looking for him.”

“Did he

look anything like me?” I asked.

He

looked me over and remarked that he guessed I was the chap. I told him I would

be glad to ride back with him and got on behind and we went back to the foot of

the mountain. He then reported me to Colonel Young and the latter ordered me bucked

and gagged for twelve hours. But I kicked on that saying, “No, I will not be

bucked and gagged. No man can live in that shape twelve hours and I won’t die

like a dog with a root in my mouth.”

“I have

my orders,” said the officer of the guard.

“And you

have heard what I said to them,” I replied.

|

| The officers of the 90th Ohio pose in their camp near Huntsville, Alabama in early 1865. |

He went

to Colonel Young and got the order countermanded by agreeing to stand good for

my safekeeping. He was Lieutenant Tonnahill of the 65th Ohio. In a

few days we were court-martialed. General Thomas J. Wood of the Third Division

was judge advocate. This being our first experience in this direction we were a

little anxious as to the outcome and we did not have long to wait. I have just

to remark that a court-martial is a short horse and soon curried.

“Guilty

or not guilty?” they asked us.

“Don’t

know what you’d call it but we certainly killed the hog,” we replied.

Then the

old judge spoke up and said, “They are guilty. Stop four months’ pay and give

them 40 days’ hard labor of eight hours each day.” And we got it. I will just

say that when the proceedings were sent to our good old Colonel [Isaac Ross] he

poked them into the fire and we got our pay just the same.

I do not care to detail the hardships we endured the three weeks we were under guard, but I look back on them as the hardest part of my army life. I have omitted the bitterest parts of the story because I do not care to live it all over again as we sometimes term it.

D.C. Goodwin, Co. E, 90th O.V.I.

Goodwin

went on to be a superb soldier and by the end of the war was one of the regiment’s

color bearers.

Source:

Harden,

Henry O. History of the 90th Ohio Volunteer Infantry in the War

of the Great Rebellion in the United States, 1861 to 1865. Stoutsville:

Press of the Fairfield-Pickaway News, 1902, pgs. 21-24

Comments

Post a Comment