McKee's Last Missive: The 15th Wisconsin and Knob Gap

On the first day of the Stones River campaign, the courage of the 15th Wisconsin was put to the test at Knob Gap near Nolensville, Tennessee. General Alexander McCook's corps had marched south from their camps at Nashville that morning and as morning turned to afternoon, the skies let loose and the troops quickly found themselves tramping along muddy roads. Ahead lay a Confederate cavalry outpost supporting a battery covering Knob Gap, and General Jefferson Davis wanted the guns taken.

"We know that if that gap is gallantly defended, the task of taking it is no easy one," recalled Lieutenant Colonel David McKee. "Colonel Carlin turns around with his usual coolness and firmness and gives his orders. “Lt. Col. McKee, you will take command of the line of skirmishers and advance them rapidly.” A single “yes sir” and I know where my post of duty is and go to it."

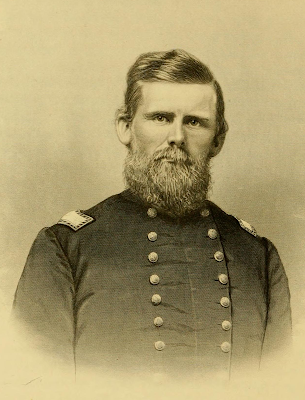

Lieutenant Colonel McKee of the 15th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry was a rarity in his regiment; a native born American of Irish parents, McKee was one of the minority of non-Scandinavians in the regiment. McKee had served previously as a captain with the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry and seen action at Bull Run before being promoted into the 15th Wisconsin. He would meet his end five days after Knob Gap in one of the opening clashes of the Battle of Stones River, Tennessee.

McKee's account of the action at Knob Gap was published in the January 13, 1863 edition of the Grant County Herald of Lancaster, Wisconsin. McKee's death left his Pamela alone to raise two orphaned girls that the couple had adopted before the war.

To learn more about the engagement at Knob Gap, please click here to read "Capturing the Gun at Knob Gap with the 15th Wisconsin" and for a perspective from the 101st Ohio, check out "Charles Barney Dennis at Stones River Part I: Engagement at Knob Gap."

In the field near Triune,

Tennessee

December 28, 1862

Friend Cover,

The

Army of the Cumberland got itself in motion on Friday December 26th.

I assure you it was a great relief to almost all of us to again be put to work

and taking the right direction toward the center of Dixie. When the order came

to move to the front, a shout of “Bully for Rosecrans” rent the air everywhere

and everybody was delighted with the prospect after having remained

comparatively inactive in camp for several weeks. Davis’ division, which is the

extreme right of the right wing of the army, took the lead. This division is

composed of three brigades: the First commanded by Colonel P.S. Post, the

Second by Colonel W.P. Carlin, and the Third by Colonel William Woodruff. Post’s

brigade was in the advance followed by Carlin then Woodruff.

Davis’

division proceeded on a somewhat circuitous route to Nolensville. He was

supported on the left by General Sheridan’s division, and I am informed that

General Negley had proceeded on the Franklin turnpike which was still to the

right of Davis. About 1 o’clock in the afternoon, the division arrived in front

of the enemy’s camp at Nolensville and found them drawn up in line of battle ready

to receive us. Pinney’s 5th Wisconsin Battery opened the fire with

shells at moderate range but the enemy being pretty well under cover of the

hills, it is not supposed that much damage was done. In a few moment, they

replied with considerable vigor.

|

| Private Martin Norda, Co. I, 15th Wisconsin |

Post’s

brigade was drawn up in line to support Pinney’s battery and skirmishers were

thrown out to the front when musketry fire was opened but not yet very heavily.

Carlin’s brigade was formed rapidly on the right of Post and advanced through a

heavy thicket of cedars to a skirt of open woods and fields, the skirmishers

being pretty well occupied with the Rebel cavalry in front until the brigade

was halted and deployed up in line. The Rebel batteries opened on us from the

left and immediately in front of Post. The order “unsling knapsacks” was given

by Colonel Carlin and was quickly obeyed by the brigade and then all was ready.

“That battery must be taken” was the order.

Carlin

swung his brigade around to the left and started for it as the battery fired

but a few rounds before it limbered up and started to the rear in the direction

of Murfreesboro. It had been raining all day. The roads were terribly muddy,

and the fields were nothing but beds of soft muck- the men sinking to the ankle

at every step. Now let me give you a slight idea of the country we were in and

in which we now had to contend with the enemy. After our brigade had swung

around and advanced and occupied the position previously occupied by the Rebels

and their battery, we were then at right angles with our first position, and we

halted for rest and for orders. In front and to our left was an open plain for

some distance in which is located the little Southern town of Nolensville.

Surrounding this plain, or rather basin, is a continuous chain of hills, high

and precipitous. Directly in our front and not man than a mile distant is a

deep cut or gorge through the mountain through which the Nolensville and Triune

turnpike passes. This gap in the mountain is not more than 300 paces in width

and is closed in by steep bluffy walls. The Rebels have taken position at this

gap and have placed their artillery and troops in it.

|

| Colonel Philip Sidney Post |

It

looks like a hard road to travel, and it is Post’s privilege to take it. While

we rest, he approaches Colonel Carlin; now remember that Post has hardly

changed his position since he first opened fire on the enemy. He asks Carlin

what he proposes to do; Carlin answers that he intends to let his men rest and

then go where he is ordered. Post is pale and has but little to say but

complains that his men are used up and cannot move. Carlin tells him that if he

(Carlin) is ordered forward, he wants Post to support his left and wants Post’s

brigade on the left of the turnpike. Post says nothing; he makes no reply.

Now an

aide of General Davis rides up with orders: “That battery must be taken at any

risk.” Carlin must do it. This is serious business; it is no child’s play. A

thought of the danger, then a thought and probably a silent tear for the loved

ones at home steals its way to the cheek of the stalwart man; not what will

become of him troubles the soldier, but what will become of them. Here are the

lives of the regiment depending upon the conduct of its officers. A slight

mistake on their part and they become, as it were, their executioners. There is

a fearful responsibility, but a moment, but a second for this reflection and

then all are nerved for the contest.

|

| General William P. Carlin |

We know

that if that gap is gallantly defended, the task of taking it is no easy one.

Colonel Carlin turns around with his usual coolness and firmness and gives his

orders. “Lt. Col. McKee, you will take command of the line of skirmishers and

advance them rapidly.” A single “yes sir” and I know where my post of duty is

and go to it. The skirmishers are deployed and pushed rapidly as possible to

the front. They are one company each from the 21st Illinois, 38th

Illinois, 15th Wisconsin, and 101st Ohio. These regiments

together with the 2nd Minnesota Battery constitute the brigade. All are

pushed rapidly forward. Three of the regiments are at times pretty well covered

by the formation of the ground; the 38th Illinois was most terribly

exposed.

The

enemy’s battery opened upon us, and shell succeeds shell with most fearful

rapidity. On, on, onward plod the almost exhausted Second Brigade. Nothing

halts them. The iron hail plunges through thin lines, over them, and in front

of them. Through cornfields and woods, up and down hills, they pursue the march

to the very cannon’s mouth. The skirmishers are near enough to open fire which

they do in good style as they advance.

The

Rebels now use canister on us. A moment more and the whole brigade opens fire

on the heads of the skirmishers who have advanced into the ravine in front of

the Rebel guns. Double quick is ordered and while the men can’t get up a trot,

they do get up a most frightful yell. The Rebels limber up to the rear as fast

as possible, but there is one place they cannot and dare not attempt to take

off. Firing ceases almost and your humble servant had the honor of being the

first man at the gun, a good six-pounder of the 14th Georgia Battery

and which had been captured from our forces at Shiloh. We got three prisoners

with it. Our loss in this charge was but eleven men in the whole brigade. Our

good luck can be attributed to nothing else but the bad management of the

gunners. Had they fought with half the gallantry with which our men advanced

upon them and stood their ground as soldiers should have done, the slaughter

must have been frightful. Their musketry fire from dismounted cavalry lasted

but a moment or two.

|

| General Jefferson C. Davis |

Our

point was carried and after following about a half mile further we were

permitted to rest. Post did not support Carlin as was expected and did not come

up until after the fight was over. Pinney’s battery took position and did good

work. We have no idea of their strength, but it was reported at 13,000. I do

not think it was more than half that number.

They

carried off a number of killed and wounded and left some few in the houses in

the neighborhood. That sight of the advancing brigade and the Rebels defending

was most grand, and worth the services of any man for one year to have

witnessed. The 15th Wisconsin claims the honor of capturing the

field piece. Colonel Heg and I were the first to take possession of it and

placed a guard over it.

Yesterday, the Rebels were followed up and driven through Triune and one more piece of artillery captured. If the Cumberland River would now rise, I have no doubt we can keep Bragg busy and get further into Dixie than we have yet been. Yesterday we heard heavy firing in the direction of Savory on the Nashville & Murfreesboro turnpike but don’t know what the result was. On to Chattanooga is the word. If we can get provisions to the army, we will soon be there.

|

| Colonel Hans C. Heg 15th Wisconsin |

Despite

the confidence shown in his letter of the 28th, Colonel McKee suspected

he would not live to see the army in Chattanooga. His friend Lieutenant Joseph

H. Rackerby of Co. E remembered that in his final days, McKee seemed to have a presentiment

of his forthcoming demise. “Just before the fight began on the 30th,

Colonel McKee told me that if he and Colonel Heg were killed, to see that his

remains were sent home and he then offered me his money and watch to keep for

him,” he wrote. “I advised him to give them to the surgeon which he did,

keeping his watch to himself. On the night of the 30th, I saw and

conversed with him again and he said that if they went into the fight the next

day, he would go on foot as there was more danger on horseback. I saw him early

the next morning [December 31, 1862] trying to rally his scattered men and as

he passed me, he said, “Joe, God bless you! Are you yet safe? This beats Bull

Run!” I saw him no more until about 8 o’clock when the lines fell back to where I

was having had to retreat across a large corn and cotton field. I turned and

saw Colonel McKee throw his hand to his head and fall. This was the last I saw

of him until after the Rebels had evacuated when I got permission to go over

the field. McKee was the first man I came to. I found that the ball had passed

direct through the brain which must have caused instant death. When I found him,

he was stripped of all his clothes except his underclothes.”

Colonel Hans C. Heg also noted McKee’s presentiment. “Poor McKee, I believe he expected to be killed,” Heg noted in a letter to his wife. “He was very gloomy the day before and in the morning before the fight began, he asked his hostler to take his horse and wanted him to take his watch and also gave Dr. Himmoe most of his money. I did not see him fall, but he was not more than 200-300 feet from me. The smoke and noise were so heavy that little could be seen or heard. We miss McKee considerable, at least I do for he was good company.”

Nine months later,

Heg himself would be killed in action at the Battle of Chickamauga.

Sources:

Letter from Lieutenant Colonel

David McKee, 15th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, Grant County

Herald (Wisconsin), January 13, 1863, pg. 1

Letter from First Lieutenant

Joseph H. Rackerby, Co. E, 15th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, Grant

County Herald (Wisconsin), February 17, 1863, pg. 2

Blegen, Theodore, editor. The

Civil War Letters of Hans Christian Heg, 15th Wisconsin Infantry. Northfield:

Norwegian American Historical Association, 1936

Comments

Post a Comment