Stopping Streight’s Raid: A Confederate View of the Ill-Fated Expedition

The story of Colonel Abel Streight’s mule raid in April and May of 1863 has previously been discussed on the blog through the diary of Color Sergeant Perry Hagerty of the 73rd Indiana, but in this post I will relay the story of the raid from the Confederate cavalry under General Nathan Bedford Forrest who pursued Streight’s force across Alabama and into Georgia.

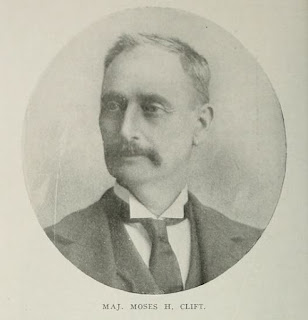

Captain Moses Haney

Clift of Chattanooga, Tennessee was the son of William and Nancy (Brooks) Clift

and was born August 25, 1836, in Soddy, Tennessee. An attorney, Clift had just begun

his law practice in Chattanooga when the war began in 1861. The issue of the

war split the Clift family: the father and two sons joined the Union army while

Moses and another brother joined the Confederacy. Moses Clift raised Co. H of

the 36th Tennessee Infantry but after seven months transferred to the

Starnes’ 4th Tennessee Cavalry and by the time of Streight’s Raid,

he was serving as the brigade commissary. By the end of the war, Clift had

risen to the rank of major and had sustained three wounds in 23 engagements

including one in which he captured his own father, the elder Clift having been

commissioned colonel of the 7th Tennessee Infantry (U.S.). It was

during the struggle for Chattanooga in the fall of 1863 that the elder Clift

was engaged in carrying dispatches to General Ambrose Burnside’s forces at

Knoxville when he was captured and brought into Confederate custody by his own

son.

He was slightly wounded during

the Battle of Dover where he had 23 bullet holes shot through his

clothes and was wounded again at Cassville and Waynesborough. He also saw

action at Parker’s Crossroads, Thompson’s Station, Chickamauga, the Atlanta

campaign, Athens, Sulphur Trestle, and Bentonville, and had command of President

Jefferson Davis’ cavalry escort between Greensboro, North Carolina and Washington,

Georgia and with General George Dibrell, was present at the last Cabinet meeting

of the Confederate government. Colonel Clift returned to practice law in

Chattanooga after the war and later became one of the commissioners for

Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Battlefield and presided over the dedication

of the Tennessee monument.

Captain Clift provided the following account of Forrest’s campaign against Colonel Streight’s ill-fated mule expedition to the May 7, 1863, edition of the Chattanooga Daily Rebel. Although not mentioned in this account, Clift's obituary mentions that "in the crisis of Streight's Raid, when General Forrest's brother had been wounded and he had lost two cannon captured by the enemy, Forrest rushed up to his two regiments 'in quite a passion' and ordered Clift to duty on his staff and moved forward in the lead."

General

Forrest with his old brigade consisting of his own original regiment [3rd

Tennessee Cavalry], Starnes’ [4th Tennessee Cavalry], Biffle’s [19th

Tennessee Cavalry aka Biffle’s 9th Cavalry], and Edmondson’s [11th

Tennessee Cavalry] regiments with six pieces of artillery 2,500 men strong,

left Spring Hill last Friday [April 24th] to go to the assistance of

Colonel Philip Roddey who was gallantly holding a force of the enemy in check

beyond and near Courtland, Alabama. The column, with Forrest at the head, moved

southward rapidly through Giles County to the Tennessee and crossed at Brown’s

Ferry. On Tuesday [April 28th] General Forrest came up with Roddey

at Town Creek, a small stream, in an open flat country studded with undergrowth

a few miles beyond Courtland in the direction of Tuscumbia. Here the united

commands attacked the enemy in force, believed to be near 10,000 under General

Grenville Dodge, with cavalry, artillery, and infantry. The fight lasted

several hours, and the artillery firing ceased about 3 p.m. Occasional skirmishing

with small arms wound up the engagement of the day and at dusk, Forrest fell

back to Courtland and threw out pickets on all the roads leading into town.

|

| Colonel Abel D. Streight 51st Indiana |

In the

meantime, a force of mounted infantry 2,000 strong under a Colonel Streight had

gone around Courtland as if designing to get in the rear of Forrest’s forces.

The next morning early Forrest started in pursuit of the party leaving a

portion of Roddey’s command in Courtland. Streight and his men, instead of

attempting to get in the rear, were really on an expedition to central Georgia

and were nearly already 100 miles away in that direction. Forrest overtook them

at Dayton’s Gap in the Sand Mountains in Alabama on Thursday [April 30th].

Here an engagement occurred in which the enemy were driven forward with the

loss of 40 killed and wounded and a few prisoners. The engagement was between

the enemy and Roddey’s and Edmondson’s commands.

About six miles further the

enemy was again overtaken by Starnes’ and Biffle’s regiments and another quick

brush of about an hour and a half’s duration occurred in which the enemy was

again driven forward, and the two pieces of artillery taken from Roddey at Town

Creek were recaptured from the enemy. In this little skirmish, 18 of the

Yankees were struck down by one discharge of our artillery, four pieces of which

were playing on them. About 15 miles south of this point our men again came

upon the enemy in ambush and another fight ensued. Our boys drove them from

their ambush by a vigorous charge. Indeed, it was one succession of bold and

desperate charges upon the ambuscaded for 300 miles and until they were finally

overtaken for the last time and captured.

The next day, the Yankees were

overhauled again at Blountsville from which place they were driven forward as

before with a loss this time of three killed and twelve wounded. Prisoners and

Negroes were captured at intervals all along the route. General Forrest still

pursued close upon their heels determined to run them down and capture the

whole party, the Yankees as fully determined to escape and burning bridges

behind them as they fled. The bridge near the town of Gadsden was destroyed,

but the enemy was driven from that town before he had time to destroy anything.

The citizens here and indeed everywhere along the route could scarcely realize

that the enemy were Yankees and many persons along the road, never for once

dreaming of such a raid from the Yankee cavalry, took it for granted they were

our own forces.

|

| Colonel Gilbert Hathaway, 73rd Indiana Infantry |

Nine miles beyond Gadsden our

men again came upon the enemy in ambush and again a fight ensued in which the

Yankee Colonel [Gilbert] Hathaway [73rd Indiana], a captain, and

several other officers were killed. The Iron Works, a few miles further into

the interior of Georgia, were set fire to by the Yankees, but only partially

destroyed and can be repaired (so the proprietor says) in a few weeks. The

Yankees were finally overtaken about two miles from Cedar Bluffs and about 26

miles from Rome. Their advance guard of 200 men had gone on towards Rome and

were checked about two miles from that city by the armed citizens.

“We have to mourn the loss of our gallant Colonel Gilbert Hathaway who was shot through the heart and almost instantly killed while cheering on his men during the fight. Colonel Hathaway, a short time before his death, placed me in command of the right wing and went over to see how Major Walker was getting along with the left. This was the last order he ever gave me and the last time I ever saw him. He was carried to the rear and taken to a farmhouse, but the brigade left before they could bury him.” ~ Adjutant Alfred Wade, 73rd Indiana

General Forrest dashed upon

them, his gallant little band by this time, after the long and tiresome

pursuit, dwindled down to an insignificant squad of 440 men. The enemy fired

one or two rounds from four little mountain howitzers they had with them, and a

slight rifle skirmish was all the fighting that occurred here. Forrest coolly

demanded their surrender and Colonel Streight, the Yankee commander, complied,

the conditions being that the captured officers should retain their side arms.

The prisoners, 1,700 in number, were then moved on fully a mile before they

were required to stack arms, actually guarded by a force four times less than their

own. In reality, it was Forrest who was the prisoner but the Yankees never

though it, and never for a moment doubted that he had a larger force in the

rear. They were, perhaps, deceived by the story of one of our men who they

captured at Dayton’s Gap who told Colonel Streight when cross-examined that “Forrest

had with him 5,000 men.”

“What brigades has he?” demanded

Colonel Streight.

“Armstrong’s, Roddey’s, and his

own!” was the prompt reply of the prisoner.

“Then we are lost, by Jupiter,”

exclaimed the non-plussed Yankee turning to his men.

And so they were, for they

surrendered their whole force in a half hour after this dialogue. The reception

in Rome beggars’ description. The entire population turned out to greet the hero

and with waving kerchiefs and amid the booming of minute guns, General Forrest

and the war-worn veterans who had followed him through flood and field, a

distance of nearly 500 miles, entered the city, welcomed by the smiles and

tears of gratitude of a thousand ladies. It was the most brilliant feat of the

war. Both the men and their leaders have won the lasting gratitude of their

countrymen and Nathan Bedford Forrest today stands at the head of the list of

cavalry chieftains of the South.

|

| Private Ambrose G. Dalton, Co. B, 3rd Tennessee Cavalry |

“It seems from the report of the prisoners that they were to have taken Rome, Gadsden, destroyed railroads and bridges, and then be paid $300 each and discharged from the Federal service. That they were fit instruments for the thieving incendiary work is sufficiently evident from the plunder found upon their persons. Silver forks and spoons, finger rings, breast pins (ladies and gentleman’s) and even children’s clothing were taken from them in profusion. Among the abolition officers I have not seen one whose countenance is stamped with the impress of a gentleman.” ~ Burr, 5th Georgia Cavalry

The object of the incursion of

the Yankees so far from their main force, aside from their intense anxiety to

avoid the redoubtable Forrest, was to reach the Georgia State Road, burn

bridges, tear up the rails, and play the “old Harry” with everything. As soon

as they found they were pursued, their escape was considered doubtful, but the

capture of even that many men would be more than compensated by the damages

they would be enabled to do the Confederates. The force under the command of

Colonel Streight consisted of the 3rd Ohio, 80th

Illinois, 51st Indiana, and 73rd Indiana, together with

three companies of renegade north Alabamians. The latter, we understand, will

be sent to Richmond and the others will be paroled.

Sources:

“General Forrest’s Late Victory,” Chattanooga Daily Rebel

(Tennessee), May 7, 1863, pg. 2

Letter from Burr, 5th Georgia Cavalry, Macon

Telegraph (Georgia), May 8, 1863, pg. 1

Diary of Alfred Wade, 73rd Indiana Volunteer

Infantry

Interesting aside, Moses Clift was an ancestor of the Golden Age Montgomery Clift.

ReplyDelete