With an Empire State Tenderfoot at Gettysburg

The 150th New York had spent the first 10 months of its service on quiet guard duty in Baltimore, Maryland. The men, well-drilled but as yet unblooded, were pulled from the Baltimore defenses in June 1863 and assigned to General Henry Slocum's 12th Army Corps to take part in turning back Lee's invasion of Pennsylvania. Captain Joseph H. Cogswell of Co. A of the 150th was one of the "tenderfoots" who marched into Pennsylvania.

"Twas the longest march our feet had ever made at one pull, and many complained," Cogswell explained. "In the night we were greeted with a soaking rain, which was by no means welcome to those who neglected to put up their tents. The rain had not ceased at sunrise nor yet at 8 o'clock, our starting hour. The slight mud was better than dust; the rain slackened and visited us by showers through the day. We made a 17-mile march Friday, halting at "Popple Springs," towards night. Many a one sought the ambulance that day, and blistered feet was the rule and not the exception. Those who had long, heavy boots suffered most. For my part, a pair of high-laced English walking shoes, with broad soles and low heels, kept me from any soreness, and I feel slight fatigue. I think the officers complained as much as the men."

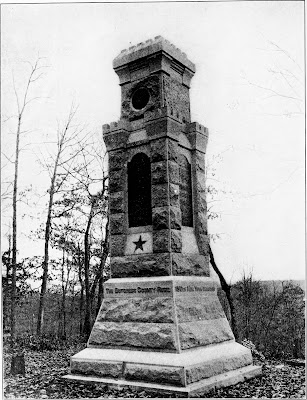

The regiment, part of General Henry H. Lockwood's brigade, arrived at Gettysburg on July 2nd and went into action on Culp's Hill where the following day, the regiment would capture nearly 200 Confederate infantrymen in their first action of the war. Captain Cogswell's account of Gettysburg appears courtesy of the New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center.

Union Infirmary, Baltimore, Maryland

Sunday,

July 12, 1863

Dear Sir,

We left Camp Belger June 25, 3 p.m., for where?

none of us scarcely knew. It came out after a time that Monocacy Junction was

our goal. We marched in dust and heat to Ellicott's Mills, (12 miles,) a

station on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and then we bivouacked under our

shelter tents. Our knapsacks had been left behind to come on by cars. The 1st

Maryland Potomac Home Brigade, Colonel William P. Maulsby, joined us on the

way, and we were under command of Brigadier General Henry H. Lockwood, from

Delaware. 'Twas the longest march our feet had ever made at one pull, and many

complained. In the night we were greeted with a soaking rain, which was by no

means welcome to those who neglected to put up their tents. The rain had not

ceased at sunrise nor yet at 8 o'clock, our starting hour. The slight mud was

better than dust; the rain slackened and visited us by showers through the day.

We made a 17-mile march Friday, halting at "Popple Springs," towards

night. Many a one sought the ambulance that day, and blistered feet was the

rule and not the exception. Those who had long, heavy boots suffered most. For

my part, a pair of high-laced English walking shoes, with broad soles and low

heels, kept me from any soreness, and I feel slight fatigue. I think the officers

complained as much as the men. We got a small piece of fresh beef for each

company that night. The rain did not fail us, and as we did not know how

essential to our success a rise in the Potomac might be, could not see the use

of quite so much of the article at the time.

At 8 a.m. Saturday, we moved, a sadder if not a

wiser lot of men. "If ever I start out on a march again, I'll know what to

wear on my feet," was an oft-heard expression. We were promised a 17-mile

march again, but it was nearly if not quite 20. We got to Monocacy Junction

about sundown, and at once pitched our tents on a hill lately chopped of its

timber, leaving the brush and stumps for our use. Our camp overlooked a large

district, and nearly the whole was filled with the Army of the Potomac.

Commissary wagons, quartermaster's wagons, ammunition wagons and headquarters

wagons were packed by hundreds, or strung out by miles. And the artillery, cavalry,

and infantry filled nearly all the space not devoted to wagons. To such neophytes

as the 150th, this was a grand and imposing sight. And at night the

thousands of campfires made a rare and beautiful spectacle, and worth all our

march to see. On Sunday we rested—of this I cannot be mistaken. Most all were

willing to obey the keeping the Sabbath in this respect. The captains had to

make out their muster rolls. We fancied we would remain and guard the large

bridge at this place, but at 4 a. m. Monday, the drum called us up, and we

found we had orders to report to the Commander of the 12th Corps,

General Henry Slocum. (I presume you know him—he was in the House when the Colonel

was in the Senate.) Our way lay through Frederick City, but before we reached

it we halted for about six or eight hours, to let three or four Army Corps pass

us. Our regiment got much ridicule for having never been out before, and were

advised to lighten their loads, which they did to a great extent, giving away

blankets, overcoats and extra clothing. By the way, the rain kept up its

visits. Our Quartermaster, with a few who had been kept back, joined us Sunday,

and brought on the knapsacks.

Our long detention gave us a short march, and

we went into camp just the other side of Frederick about 3 p.m. Here we had

more rain, and an early start the next morning. Rations began to be in demand

and our supply was limited. Tuesday, June 30th we made about 18 miles,

halting at 4 p.m. Many were out of shoes, and a great many were sore footed,

but all were good natured. Bruceville was the name the store, shop and bridge rejoiced

in; it certainly wasn't Spruceville. The country we passed through this day was

equal to western New York. The people made our extremity their harvest. One

charged and got from me 75 cents for a loaf of bread!

The next day we started "early in the

morning," on our way. We reached the "land of brotherly love,"

and headed towards Gettysburg, halting in a woods about seven miles south of

that place. We got the news of that day's fight, of the death of Reynolds, of

our being driven back, and made up our minds we were in for a fight. At 2 am.

July 2nd, the reveille started a weary lot of men from their needed

rest. The cup of coffee was soon made, the hardtack cracked, and our line was

formed. The general informed us that we must leave our knapsacks for the wagons

to bring up—that a forced march of nine miles was to be made in three hours,

and we prepared for it. Our course lay due north, and to the right of

Gettysburg. We passed General Meade's headquarters and held on our march till

we arrived to the front—the extreme right. The 12th Corps held this

position. Our line was formed, and we rested. We had nothing to do all day but

listen to the roar of cannon to the left and watch movements generally.

About 6:30 or 7 p.m., an order came for our two

regiments to hasten to help the center, and we were off, marching by the flank

right into it. Shells cracked around us soon,—dead men and defunct horses and

mules, broken wagons, caissons, and the debris of battle strewed the way.

Arriving near our place we deployed into line of battle, and pushed ahead,

beyond the line the Rebs. held, they falling back and offering us no sight of

their gray backs, for the distance. This position we held some time, and then

were ordered back to our camping ground of the day. Cos. B and G dragged off

from an adjacent field three brass 12 pounders of one of our batteries which

the Rebs had once that day. I think it was 10 p.m.. when we got back again. We

lay on our arms all night in line of battle.

Friday July 3rd at 2 a.m., we were

up again and advanced. General Richard Ewell was in front of us, and the day

before had gained a slight advantage; and made his boasts that he would have

our portion, a certain hill, if it cost him every man he had. His men were not 80

rods from us and were occupying a position of our rifle pits. We advanced

towards the woods, in line, and halted, and my company and afterwards a part of

Co. G were ordered to hold the edge of the woods as skirmishers, which we did;

the boys obeying well. A little before 4 a.m., the Colonel sent us word to

return to the lines with my company. Meanwhile Bess' Battery, (Regular) of six

light brass, 15 pounders, had been stationed on a hill to the left, and our two

regiments were ordered up to support it. Then, at just 4 a. m. they opened,

shelling the woods terribly for a half hour. Then one Maryland regiment

was ordered into these woods to drive

the Rebs out. As soon as they were well in, a rattling fire of musketry began,

and in twenty minutes our friends came out minus three officers, 20 killed and 100

wounded. The enemy had posted themselves behind a strong stone wall and had our

folks nicely. We formed again in front of the woods, but they did not come out.

About 6 o'clock we were ordered around to the

left of our position and into some rifle pits, on the brow of a hill looking

down into a valley that run out towards where our first line had been. These

pits were very long, and five or six regiments could be in them at once. Our

boys did not know where they were going, but forming line of battle, with our

colors flying, we rushed on with such a cheer as would have done your heart

good to hear. Our orders were to fire till relieved, and we did. The men

averaged 100 rounds in the two hours and 40 minutes they were in. About all the

firing was at random, as the Rebs were in the valley below or on the slope beyond, hidden by the trees and

foliage, but they were there; and so incessant was our fire that they could not

form for a charge. The valley was literally covered with dead Rebs. Some of

their sharpshooters, by climbing trees, could get at us in the pits, and sad to

tell, we lost seven good men, and 22 wounded. Co. A lost Corporal John Van Alstyne,

Private John P. Wing, Private Levi Rust and Private Charles Howgate. They were

all killed instantly. I have written to Van Alstyne's parents today. Our men

all behaved nobly. I am proud of Co. A. Lieutenant Henry Gridley was standing

at the side of John when he fell. Rust and Wing were three feet from me.

When we were relieved, we fell back out of

range, and then went in again towards noon, resting after two hour's work. At 2

p.m. "the great cannonading" of the war began, and we were under a

storm of shot and shell, yet none of us were hurt. At 4 p.m. we were drawn off

towards the center as reserves but were not called. The field had been won by

hard fighting along the whole line. July 4th we waited for orders in

a dampening rain. July 5th, ditto, till sundown, when we marched

nine miles to Littlestown, and camped. Here we got sight of our wagons and got

out shelter tents. July 6th, we marched about two miles, and rested

for the day. July 7th, at 2:30 a.m. we were called, formed line at 3, and

marched to within five miles of Frederick City, 27 miles, over the worst of

roads, and in a heavy rain. I was attacked with Diarrhea at noon, and at night

felt used up—got no supper. July 8th, marched 6-1/2 miles in the mud

and rain, and then I had to give up. I was completely exhausted and was ordered

to Frederick; but there being no place in Hospital or Hotel for a man to stay,

I was sent to Baltimore. I am better, and hope to be back soon. When I left the

regiment, they were on their way west from Frederick City, chasing up Lee.

Quite a number of the boys gave out from exhaustion, at Frederick. Sergeant

Borden for one, George Willson, Color Corporal of my company, was struck in the

forehead by a ball, but only slightly injured. Corp. W. C. Willson was left

behind, sick in hospital here.

I believe I have now given you a correct

"log" of our operations. If it is worth reading, peruse it. It is

well to give such advice on the last line.

Very

respectfully, your obedient servant,

Joseph

H. COGSWELL,

Capt.

Co. A, 150th N. Y. S. V.

Comments

Post a Comment