The Yankees are Buried Shallow: A Civilian’s View of Brice’s Crossroads

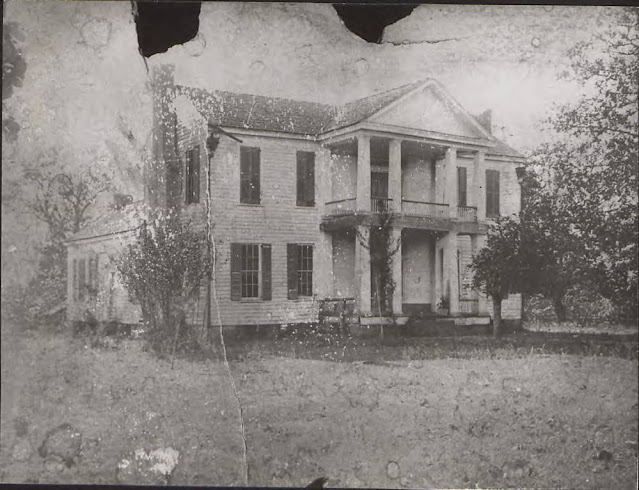

The carnage surrounding his family’s homestead near Guntown, Mississippi in the aftermath of the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads left local resident Samuel Agnew speechless. The war had been brought literally to his doorstep.

“I walked

through the rooms and found everything turned upside down and nearly everything

we had taken from us,” he wrote in his diary. “Dead and wounded men were lying

in the house. The walls of the house had been perforated by a good many

bullets. Negroes and white men both plundered the house, and nothing could move

their hearts to pity, but with vandal hands they rifled trunks, bureaus, and

rooms. The garden and yard fences were torn down. Before I reached the house, I

found the road filled with shoes and articles of every description which had

been thrown away by the Federals in the retreat. Soldiers lay stretched

cold in death on the roadside. I saw two before I came to the gate. When I saw these

things, I knew that Forrest had gained a great and complete victory, but my

heart sank within me at the prospect of our own losses.”

The following excerpts from Reverend

Agnew’s diary were sent to Captain John W. Morton of General Nathan Bedford Forrest’s

command in February of 1883. Agnew sent this information along to Captain Morton

in hopes that the famous artillerist would use it in a future article

describing the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads. But Captain Morton felt that Agnew’s

account was so compelling and unusual that he provided it to the editors of Southern

Bivouac magazine who ran the diary as a stand-alone article ran under the

title of “Confederate War History: Tishomingo Creek, or Guntown, Where Sturgis

and Grierson Were Badly Worsted” in their May/June 1883 issue.

The University of North Carolina now owns the original diary as part of their Southern Historical Collection. A full transcript of the diary covering from September 27, 1863 to June 30, 1864 can be found here.

Diary of Samuel A. Agnew, Guntown, Mississippi

June 8, 1864

This morning is dark and

lowering and before breakfast it commenced raining. It bids fair to be a very

rainy day. There has been some excitement today growing out of the Yankee raid.

Forrest has gone up country. He passed yesterday evening and I learn today is

repairing the bridge across Twenty-Mile Creek near Burres. Trains brought up

his artillery to Baldwyn last night and this morning he evidently is striking

toward Corinth as the point of danger. Our intelligence is that the Yankees are

at Ripley. I cannot learn which way the Yankees are going, some think they are

moving toward New Albany, others towards Rienzi or Corinth. There force is said

to be seven regiments of infantry at Muddy Creek, four of which are Negroes,

2,500 cavalry, 250 wagons, 150 ambulances, and large quantities of artillery.

June 9, 1864

The news we

had was that Rucker had gone from Baldwyn with his brigade towards Rienzi while

General Forrest with his entire command has gone to Rienzi. The Yankees were

reported to have gone in the same direction. We hence felt very easy thinking

that for the present we would not be troubled with the Yankees. Late this

evening Thompson Phillips came over telling us that Oliver Nelson had sent word

down that the Yankees were coming down the Ripley road this evening and it was not

know whether they would go towards Baldwyn or Guntown. Sent the mules off to

the woods lot. Brought in the mules at dark. We discredited the news of the

approach of the Yankees.

June 10, 1864

The morning

was cloudy. At breakfast we learned that the Yankees camped at Stubbs’s last

night although we did not suppose they would travel this road. Went out early

with the mules into the woods back of Watson’s field. Went over to Uncle Joe’s

to notify him of the report and got lost on the way. While at Uncle Joe’s,

heard a roaring towards Lyon’s Gin which I did not understand; came on back and

stopped at the end of the lane to take observations and while there heard two

horsemen approaching down through the thicket in back of the farm. I awaited

until I could hear them conversing then put my horse to the run and escaped to

the thicket. I have reason now to think that the approaching horsemen were Yankees.

About 10 o’clock

heard the report of a cannon toward Baldwyn. Suppose that the enemy had gone

down to the Baldwyn road and met Forrest. Walked over to the western fence of

the Watson field to note the direction of the cannonading and concluded it was

about the crossroads. The cannonading continued with brief intermissions for

several long hours. While at the Watson field I saw Arch, one of my father’s

Negroes, skulking through the woods. He told me that the Yankees were at our

house and had taken everything we had to eat. About 50 wagons were in front of

the house and the yard was full of thousands of Negroes. This was bad news, but

I hoped that Arch being badly frightened had exaggerated. But his news caused

us to keep quiet and not attempt to communicate with the house.

I listened

intently and anxiously to the firing. The battle waged long and doubtfully for

some time in the direction of the crossroads. About 5 o’clock the firing

evidently grew nearer, and I was satisfied it was near Holland’s. About 6 p.m.

to my surprise shells began to fall in the woods where I was hiding, when I was

near the Watson field taking observations. Shells coming over rapidly with a whizzing

noise such that I deemed it prudent to get out of the way. Just as we were

leaving the back of the field, I heard some person talking near us; I supposed

it was Pa conducting mother and the family to a place of safety and came very

near going to their assistance, but just then a shell came whizzing with a peculiarly

unpleasant noise over my head and I betook myself to the mules.

I saw Uncle

Joe [Agnew] in the woods, and he told me the Yankees were in our wheat field in

thousands. He could give no intelligence from home, and I was greatly uneasy.

The battle was then evidently raging there. The battle at the crossroads was

very severe. The ground all around the crossroads is covered with the wounded

and dead. The enemy fought desperately making a stubborn fight, but finally

were driven back and at last accounts the fighting was going on about our

house.

June 11, 1864

I was in the

woods all night and it was showery. By light I was up and walked over to Uncle

Young’s but received no additional information. I was very anxious in reference

to the family at home and came up on home cautiously and found that the

Federals had been driven away. Our once pleasant home was a wreck; my very

heart pained me when I saw the desolation wrought. Thanks to a merciful God,

the lives of the family were preserved although they were exposed to great

danger. The garden and yard fences were torn down. Our yard was full of horses.

Soldiers were stalking through the yard and house without any ceremony. Federal

wagons lined the road. Before I reached the house, I found the road filled with

shoes and articles of every description which had been thrown away by the

Federals in the retreat. Dead Negroes lay stretched cold in death on the roadside.

I saw two before I came to the gate. When I saw these things, I knew that

Forrest had gained a great and complete victory, but my heart sank within me at

the prospect of our own losses.

I found

mother, Nannie [Agnew's wife], Mary [Agnew's younger sister], and Margaret on the back piazza. They were laughing and

talking but under their mirth I thought I could see sadness concealed. They

told me the Federals had taken from us every ear of corn and every pound of

meat leaving nothing to eat and that the house had been plundered. I walked

through the rooms and found everything turned upside down and nearly everything

we had taken from us. Dead and wounded men were lying in the house. The walls

of the house had been perforated by a good many bullets. One shell struck the

gutter on the south side of the dining room. Negroes and white men both

plundered the house, and nothing could move their hearts to pity, but with

vandal hands they rifled trunks, bureaus, and rooms. They entered every room

but the catch all. Even the Negroes were robbed of their clothing. The Negroes

were especially insolent. As they passed down the road, they shook their fists

at the ladies and told them they were going to show Forrest that they were his

rulers. As they returned, their tune had changed. With tears in their eyes,

some of them came to my mother and asked them what they must do? Would General

Forrest kill them? Poor fools, many a simpleton lies rotting along the road

this day. I felt sorry when I first saw them lying dead, but when I heard how

they did I lost all my sympathy for the black villains.

The Yankees

acknowledged on the retreat that they had got the worst whipping they ever had.

On the retreat, Sturgis was in front going at a trot. Two Yankees surrendered

to mother before the battle here and remained in the house during the fight.

While the fighting was going on at the crossroads there were Yankees on this

place all the time. When it was evident there would be a fight here, a Yankee

told mother that she had better leave the house as the Rebels were going to

shell it. They told the Negroes that if the whites left the house, they would

burn it. When the fight commenced, mother and the rest of them closed the doors

and window blinds and lay flat on the floor in Margaret’s room at the center of

the house and remained safely until our men drove the Yankees away.

The yard was a

battleground with the Southerners on the south side and the Yankees next to the

crib. The Yankees made a breastwork of the picket fence between the yard and

the crib lot. The Yankee battery was in front of our gate. Rice’s artillery was

just below the garden. The fight here was nearly as stubborn as at the

crossroads. Captain Rice told me that the artillery saved the day here as when

he came up, the cavalry was retreating. The cavalrymen say this was the only

time the artillery ever did them any good. In front of the house the marks of

the bullets are plainly to be seen. My heart was so full because of our

situation that I could hardly talk.

June 12, 1864

Sabbath was a very

rainy day and such crowds as have been passing; so many guns have been firing

and so many persons have been about the house that it has not seemed like a

Sabbath. Pa, Uncle Joe, and John Martin took the Negroes and buried the Yankee

Negroes whose bodies lie nearby. It rained so much that they had to suspend

operations until this afternoon. Some

Federal prisoners, four in number, were brought in this evening to assist in

burying the dead: they were from Pennsylvania, Minnesota, and Illinois. They

are down on their officers and say that in a fight they were always in the rear

and on a retreat in the front. Three white men are buried near us: Rice of the

7th Tennessee, Henry King of Rice’s battery, and A.J. Smith. The

Yankees are buried shallow, the Negroes especially so. Sat about the house the

entire day doing nothing of great moment. Pa had the Negroes repairing the

fences deeming it a work of necessity. The people are riding over the

battlefield from some distance; although the day was rainy, I notice many

ladies riding over the road.

|

| General Nathan B. Forrest "was in a bad humor having been informed that the citizens have been stealing many things from the Yankee wagons." |

June 13, 1864

The road has still

been the scene of continued traveling by the soldiers. The wagons which were

captured are being taken down the road. Forrest has made a rich capture. This

morning I walked over the ground near us, finding many dead horses and mules

and the stench is great. General Forrest passed back today. I note nothing

special in his appearance and understood that he was in a bad humor having been

informed that the citizens have been stealing many things from the Yankee wagons.

General Buford also passed; he is a large chuffy man. General Lyon also went

down. A Good many troops passed down today. The pursuit of the enemy has been

discontinued.

Eight hundred

Yankee prisoners were passed down today under guard. It is impossible to find

one who will acknowledge that he ever plundered. One remarked as he came up “Here’s

the man that caught your turkeys,” while another one was heard to say, “Here’s

the place where we got the wine.” Some officers were among them and

nice-looking men they were. A few negroes brought up the rear, but most of the

Negroes were shot, or so reported. Our men were so much incensed that they shot

them whenever they saw them. The prisoners pointed out their positions here. One

was in the yard, one in the road, and another in the woods. One pointed out a

tree and said, “I shot a big fat Rebel from behind that tree.” Representatives of

a good many regiments were along; some from the 9th Minnesota, 2nd

Iowa Cavalry, and the 114th Illinois, etc.

June 14, 1864

Affairs are

becoming quieter but there are many still passing. I found the roads badly cut up

by the wagons and artillery that are passing every hour. The lane of Mrs.

Phillips has become impassable, and the wagons go in by Mrs. Phillips’ house

now. I saw several newly made graves by the roadside and the Negroes covered

with very little dirt. The stench from the dead horses is almost insupportable.

It is sickening to pass along the roads.

I rode over to Brice’s and saw

marks of the battle but not so apparent as I had supposed from the great

firing. Brice’s house and yard are public property now; sick men occupy the

rooms some poor fellows are mortally wounded. I felt sorry when I looked on the

poor fellows dying so far from dear ones at home. They are lying on pallets.

Some Yankees are also there. The church seems to be occupied by sick and wounded

prisoners. The principal surgeon was operating on a Yankee while I was there:

he was lying on a table insensible, being under the influence of chloroform.

His right foot had been amputated and his left hand half taken off.

June 16, 1864

The stench of

the dead is very unpleasant. Pa had the carcass of a horse burned a few days

ago. I notice down in Phillips’ lane the grave of a Yankee with the hand

projecting out. I think it is a white man though the hand looks black. I think

the enemy’s dead are buried too shallow. The graves are not two feet deep and

very little dirt conceals them from the eye. Some apprehend that this stench

will produce sickness. Soldiers are still passing. Some of them are rough

cases. We have in our army some as vile men as the Yankees can have.

Source:

“Confederate War History: Tishomingo Creek, or Guntown, Where

Sturgis and Grierson Were Badly Worsted.” Samuel A. Agnew, Southern Bivouac,

May/June 1883, pgs. 356-365

Comments

Post a Comment