Confederate Vanguard: Ector's Texans Open the Battle of Stones River

On this blog, I have written quite a few posts about the opening moments of the Battle of Stones River, examining the events of the early morning hours of December 31, 1862 from the perspective of the men of General Richard W. Johnson’s division. Today we flip the coin and view the Confederate army’s dawn assault through their own eyes with a focus on the Texans of General Matthew Duncan Ector’s brigade of dismounted cavalry.

Ector’s brigade consisted of the 10th, 11th, 14th, and 15th Texas Cavalry regiments. The 15th Texas Cavalry Regiment (Dismounted) as it was known during the Stones River campaign is a misnomer; the regiment was borne upon the rolls of Texas as the 32nd Texas Cavalry; the proper 15th Texas Cavalry was also dismounted but at this period of time (December 1862) was based at Arkansas Post where it would be captured in early January 1863.

On Monday December 29, 1862, Ector’s brigade and the balance of General John P. McCown’s division marched west from their winter camps at Readyville, Tennessee. The 15-mile march took up most of the daylight hours and in the late afternoon the Texans took their position on the left flank of General Braxton Bragg’s army, moving out along the Franklin Pike. As the Federal Right Wing pushed across Puckett Creek and took their positions east of Gresham Lane on the afternoon of December 30, the skirmishers of McCown’s Division came under Federal artillery fire but sustained few casualties.

As sun set on December 30th, the Yankee skirmishers fanned out into the fields along and south of the Franklin Pike where they were confronted by their Confederate counterparts. A mere 300 yards behind the Confederate skirmishers lay McCown’s division, with Ector’s men at rest along a farm lane bordered on both sides by a cedar rail fence. The presence of Federal artillery so close to the Confederate lines was a cause for concern by Colonel Matthew F. Locke of the 10th Texas, whose regiment lay directly across the field from the deadly guns. “It was apparent that the fence which had obstructed the sight of the enemy would serve as an auxiliary in the enemy’s hands if our position was discovered,” [Locke’s regiment took five quick casualties when a cannon ball struck the fence just before sunset; a full battery of cannon sending shells into the fence would create a cloud of deadly wood shards that would quickly obliterate his regiment.] Knowing this, although the weather was very inclement and disagreeable, I did not allow any fire and the blankets having been left at camp, the men suffered very much and but for the fact that they had been lying on their arms without sleep for two nights previous, sleep would have been impossible.”[1] Private Lewis P. Jones of Co. I of the 10th Texas recalled that the men tore down the section of fence closest to the enemy. “We spread the rails out over the ground next to the opposite string which was left for breastworks. On the rails, we passed the night without fires, most of the men sitting down watching the fires of the enemy some 400 yards away.”[2]

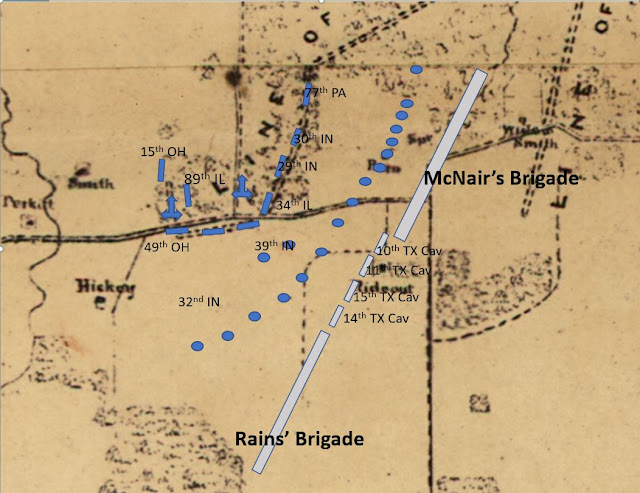

General Evander McNair’s brigade of Arkansans held the divisional right, Ector’s Texans the center, and General James Rains’ brigade held the divisional left; beyond Rains were the troopers of General John Wharton’s cavalry brigade who moved into position during the overnight hours. In brigade alignment, the 10th Texas Cavalry was on the right with their flank resting near the Franklin Pike and angling southwesterly was the 14th Texas, then the 15th Texas, with the 11th Texas on the brigade left flank. McNair’s and Ector’s brigades had served for a long time together and devised nicknames, McNair’s Arkansans were called “Joshies” by the Texans and the Texans were called “Chubs” by the Arkansans, both parties maintaining a warm regard for the fighting abilities of their fellow trans-Mississippi comrades in arms.[3]

|

| Colonel Julius A. Andrews, 15th/32nd Texas Cavalry |

“On Wednesday morning [December 31, 1862] my regiment was awakened and ordered to be in line of battle at 5 o’clock,” wrote Colonel Julius A. Andrews of the 15th Texas. “We remained in line until 6:30 at which time we were ordered to move forward.”[4] It had been a damp, bone-chilling night for the Texans. “There was a drizzling rain falling which froze as it fell; we had only one blanket each and were not allowed to have any fire,” recalled Benjamin S. King of Co. F, 15th Texas. “In the morning, the orderly gave us a gill of whiskey each and ordered us to charge. This was before daylight and it was so cold that water would freeze in our canteens.”[5] Colonel Locke of the 10th Texas recalled that is was “difficult to restrain the expression of joy and outburst of feeling manifested by the men at the opportunity being presented upon an open field of relieving ourselves from our unhappy condition and of deciding the fate of the Confederacy.”[6] The entire division marched off together at the crack of dawn.

The Federal skirmish line directly in front of the Ector’s brigade consisted of men from the 32nd and 39th Indiana regiments of General August Willich’s brigade, and Cos. A and B of the 34th Illinois of General Edward N. Kirk’s brigade. “A cornfield stretched to the front for half a mile then a belt of timber with woods on our right and left,” recalled Sergeant Will Robinson of the 34th Illinois. “To our rear was a grassy field 20 rods wide then another cornfield 80 rods across divided by a rail fence. We were hidden by a high fence which had partially protected us from the cold December wind.”[7] Corporal Henry Rankin of the 39th Indiana instructed his squad to “give way at the first gun and make for our reserve. I had placed the last pickets on duty before daybreak and had scarcely reached my reserve and packed up my knapsack when the first gun was fired on my pickets. They could scarcely be seen and looked more like trees than pickets.”[8]

The Federals in the main line had been awake since 5 a.m. First Lieutenant Shepherd Green, acting assistant adjutant general of General August Willich’s staff, arose at dawn. “We rose from our beds of blankets and corn blades and began eating our meal of hard bread and bacon,” he later wrote his father back in Ohio. “All seemed quiet; not even the firing of a single gun broke the ominous silence.”[9] Sergeant Edwin Payne of the 34th Illinois noted that “there being no indications of the enemy advancing, the order was issued to prepare breakfast. The meal was frugal and soon ended. Meantime, a portion of the artillery horses (about one third of the whole number) were taken to water and the remainder standing ready to hitch to the pieces on the first indication of danger. At precisely 6:22, and not ten minutes after the dawn of day, a brisk firing was heard upon the extreme right of Kirk’s line. It was evident the enemy had commenced the movement against our right.”[10]

Sergeant Major Lyman Widney of the 34th Illinois had walked out into the field behind his regiment’s skirmish line when he met one man running back. “As he passed me, he exclaimed, ‘They’re coming’ and continued on to the regiment to give the alarm. As all was so quiet, not a shot having been fired, I felt decidedly skeptical and walked still further out until the enemy’s breastworks were in view and there, sure enough, a succession of long lines of gray were swarming over the breastworks and sweeping towards us but not yet within gunshot range.”[11]

As the noise of the stomping, crunching feet of 4,400 Confederates moving through frozen muddy fields echoed across the damp stillness of pre-dawn, the first shots of the battle were fired by the 39th Indiana. At 300 yards from the main Federal line, Ector’s men picked up the pace, moving at the quick step and charging in silence; no Rebel yell at this point. The frightened skirmishers running back into camp served to put Johnson’s division on notice that the battle had begun. “Bang went a gun on the extreme right quickly followed by others and in a moment every gun was at work firing through the fence,” Will Robinson recalled. “By this time, the Rebel infantry had reached the fence with the lone star ensign of Texas in advance. A Rebel flag bearer planted his hateful colors and yelled out “Run you damn Yankees!”[12]

General Edward N. Kirk reported that “we could see them advancing over the open country for about a half mile in front of our lines. They moved in heavy masses, apparently six ranks deep. Their left extended far beyond our right, so as to completely flank us. They moved up steadily and in good order without music or noise of any kind,” he reported.[13] Captain Warren P. Edgarton’s Battery E of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery had two of its six guns in position near Gresham Lane; the guns were quickly loaded, the cannons angled to the southeast, and opened fire over the heads of the retreating skirmishers. Ector’s men charged about 300 yards in total when they stopped and aiming for the flash of Edgarton’s guns, let loose with a volley, followed by a resumption of the charge. “We poured a hot and deadly fire into them and continued the advance,” reported General Ector. “Such determination and courage was perfectly irresistible. My brigade was within 30 yards of their cannon when their cannon fired the second round. Quite a number of my brigade were killed and wounded, but the gaps made by the canister and small arms were closed up in and instant. The infantry gave way about the time we reached their battery. We pressed them so rapidly they soon gave way a second time.”[14]

On the right of the line, Locke’s 10th Texas bore the brunt of the canister blasts from Edgarton’s guns but soon got into a hand-to-hand scuffle with the 34th Illinois. In one of his last commands on the field that day, General Kirk ordered the Illinoisans to charge into the field to buy time for the rest of the brigade to get into position. It was incredibly brave, and incredibly foolhardy: 354 men trying to stop 4,400. The color bearers of the two regiments caught sight of one another and a deadly struggle for possession of the flags commenced in which the 10th Texas came out the victor. “The enemy’s lines being formed immediately in our front, their standard bearer, directly in front of mine, was waving his flag, casting it forward, and by various motions urging the Federal column forward,” wrote Colonel Locke. “Sergeant Andrew Sims [Co. D], flag bearer of this regiment, discovered him and pressed forward with incredible speed directly toward the enemy’s banner and on reached with a pace or less of his adversary, he planted the Confederate flag firmly upon the ground with one hand and with a manly grasp reached the other after the flagstaff of his enemy. But the other gave back, and in that movement they both fell in the agonies of death, waving their banners above their heads until their last expiring moments.”[15] Edwin Payne of the 34th Illinois reported that “five color bearers fell in quick succession but as fast as they fell, the flag was raised aloft and flaunted in the face of the foe. The entire color guard being killed or wounded, the colors over which so much precious blood had been spilled were trailed in the mud and borne off the field by the hands of the enemy.”[16]

|

| Lt. John Thompson Beall Co. C, 14th Texas Cavalry |

The fight was short, sharp, and bloody, the 10th Texas losing 80 men, nearly a third of the regiment, in the opening moments of the battle. Elbridge G. Littlejohn was among those struck down early. “The order to charge came down the lines with electric speed and onward we went dashing with a furious yell,” he related in a letter to his wife. “They stood but a moment then they fled in disorder. But as they were running, they did not forget to shoot. I had shot my gun once, loaded again, and was within a few steps of the spot where we took their flag when a Minie ball hit me on the right hip bone and scaled off a little piece of the bone. The ball passed out through the fleshy part of my thigh It is not serious wound, but I assure you it hurt very badly. But while I was lying on the ground, a canister shot from our own guns hit me on the top of the head. I thought then I was gone, yet I was perfectly conscious of everything that was transpiring.”[17]

In the 11th Texas, Colonel John C. Burks was mortally wounded leading his Texans against Edgarton’s guns. “Holding his hand on the wound to control the bleeding, he continued at the head of his command, urging his men forward, until he lost consciousness,” it was reported.[18] Thomas H. Colman of Co. F remembered the “roaring of cannon, our colonel falling pierced through the lungs with a Minie ball in the very commencement, his last command being ‘Forward my brave boys!’ and after he was carried off the field his last dying words were inquiring about the regiment. He was a noble man.”[19]

|

| Flag of 11th Texas Cavalry |

Once the 34th Illinois was swept from the field, Ector’s Texans barreled into the two Federal brigade camps amongst the scattered timber at the intersection of Gresham Lane and the Franklin Pike. “The boys drove the enemy back into their camps which were well-lit with fires around which they were cooking breakfast,” Lewis Jones of the 10th Texas related. “The onslaught was so sudden and the slaughter so great that they retreated in great confusion, every fellow for himself and devil take the hindmost. They had abandoned everything to get away. One of their dead some 200 yards to their rear had been killed still holding firmly his pot of coffee.”[20] Lieutenant J.T. Tunnell of Co. B of the 14th Texas recalled that “many of the Yanks were either killed or retreated in their nightclothes. We pursued them with a Rebel yell. In advancing, we found a caisson with the horses attached lodged against a tree and other evidences of their confusion. The Yanks tried to make a stand whenever they could find shelter of any kind. All along our route, we captured prisoners who would take refuge behind houses, fences, logs, cedar bushes, and in ravines.”[21]

The chaos of the sudden attack spread from Kirk’s to Willich’s brigade encamped nearby. ”We had just got our coffee ready to drink when bang, bang went several guns on the picket line immediately in front of our brigade and the next second volley after volley and the bullets were whistling in too close proximity to our heads to be comfortable,” remembers Lieutenant Samuel S. Pettit of the 15th Ohio. “The cry to arms came up to the regiment from Colonel William Wallace. We left our coffee, threw down our tents and blankets in a pile and sprang for our arms. By this time, we could distinctly hear Rebel cheering. They were charging our batteries. We were taken by surprise. The men became panic-stricken. We returned fire but the Rebels were now coming over yelling like so many savages. This sent terror among our already broken ranks and then there was skedaddling on our part.”[22]

Panic, destruction, and terror. The dawn attack of McCown’s

division succeeded in cracking the Federal line south of the Wilkinson Pike,

and for the remainder of the morning, brigade after brigade of the Right Wing

found themselves scrambling into position to face the Confederate tide that

came rolling north from the Franklin Pike. It was a bloody affair for all

involved, but the spoils in this initial contest nearly all fell to the

Confederates: one General captured (August Willich), one General wounded and

out of action (Edward Kirk, who would die in July 1863 of the effects of the

wound), ten cannon captured (all of Battery E, 1st OVLA and four of

six guns of Battery A, 1st OVLA), hundreds of Federals killed or

wounded, hundreds of prisoners taken, and the Federal army starting off the

battle on the run. It was a spectacular battlefield success for the

Confederates, and it would take much hard fighting and sacrifice on the part of

the Army of the Cumberland to recover from the misfortunes of the dawn of

December 31, 1862.

[1] Official Report of Colonel Matthew F. Locke, 10th

Texas Cavalry, O.R.

[2] Account of Private Lewis P. Jones, Co. I, 10th

Texas Cavalry, Confederate Veteran, 1923, pg. 341

[3] “About Ector’s and McNair’s Brigade,” J.G. McCown,

Co. K, 15th Texas Cavalry, Confederate Veteran, March 1901,

pg. 113

[4] Official Report of Colonel Julius A. Andrews, 15th

Texas Cavalry, O.R.

[5] Reminiscences of the Boys in Gray, 1861-65,

pg. 404

[6] Locke report, op. cit.

[7] Sergeant Will C. Robinson, Co. A, 34th

Illinois Infantry, Sterling Republican Gazette (Illinois), January 24,

1863

[8] Corporal Henry N. Rankin, 39th Indiana

Infantry, “Midwinter Battle of Stones River,” National Tribune, July 22,

1926

[9] First Lieutenant Shepherd Green, 49th Ohio

Infantry, Ottawa Telegram (Ohio), February 7, 1863

[10] Payne, Edwin W. History of the Thirty-Fourth

Regiment of Illinois Volunteer Infantry. Pg. 43

[11] Sergeant Major Lyman Widney, 34th

Illinois, National Tribune, October 10, 1901, pg. 7

[12] Robinson, op. cit.

[13] Official report of General Edward N. Kirk, Rebellion

Record, Volume VI, pgs. 129-131

[14] Official Report of Brigadier General Matthew D.

Ector, O.R.

[15] Locke report, op. cit.

[16] Payne, op. cit., pg. 44

[17] Letters of Elbridge G. Littlejohn, 10th

Texas Cavalry, Stones River National Battlefield Regimental Files

[18] Burks, John C. The Handbook of Texas Online,

retrieved August 20, 2003.

[19] Colman-Hayter Family Papers, Folder 6, Western

Historical Manuscript Collection-Columbia, Missouri

[20] Jones, op. cit.

[21] “Texans in the Battle at Murfreesboro,” Lieutenant

J.T. Tunnell, 14th Texas, Confederate Veteran, 1908, pg. 574

[22] Second Lieutenant Samuel S. Pettit, 15th

Ohio Infantry, Wyandot Pioneer (Ohio), February 6, 1863

Comments

Post a Comment