With the 37th Mississippi at Peach Tree Creek

Long after the Civil War, Reverend Washington “Wash” Bryan Crumpton wrote a memoir entitled A Book of Memories of his wartime experiences while serving as a sergeant in the ranks of Co. H (the Jasper Rifles) of the 37th Mississippi Infantry. The following account of the Battle of Peach Tree Creek, excerpted from Crumpton’s book, was published in the October 1921 edition of Confederate Veteran. The 37th Mississippi was assigned to Cantey’s Brigade was led at this time by Colonel Edward A. O’Neal, and was part of General Edward C. Walthall’s division of A.P. Stewart’s corps.

|

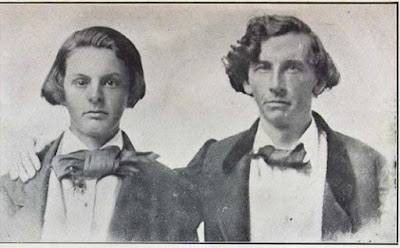

| Washington B. Crumpton at left in a pre-war image taken with his brother H.J. After the war, Wash became a minister and noted author. |

Wash's account captures the confusion endemic in war, and he opines that the real reason why the Confederate attack failed at Peach Tree Creek was the fact that his comrades were a little too eager to escort Yankee prisoners to the rear, and by so doing, left the front line with inadequate numbers to exploit their initial successes.

As we crossed the Chattahoochee River, the boys said, as

they had said many times before, “Old Joe is going to cross this river and make

his stand.” But on we went until we were in the suburbs of Atlanta. Then rumors

began to reach us that Johnston had informed the war Department that Atlanta

could not be defended and after a little, if the army must be saved, it must be

evacuated. However, plans had been made to attack the enemy but before the fighting

Johnston was relieved.

On the 20th of July, the battle of Peach Tree

Creek. I have forgotten the military terms, but the plan of attack was for our

regiment to halfway overlap the one in front. We took the Yanks in our front

seemingly by surprise. They were mostly foreigners who couldn’t speak English.

They threw down their guns and surrendered in droves and that was our undoing.

Too many of our fellows were willing to carry prisoners to the rear, so there

was no reserve to carry on the victory.

Stone’s Brigade on our right had come up through an old

field facing a battery and had been unsuccessful. Lieutenant Pierce English,

gun in hand, and three of us found ourselves on a hill rather behind the battery

on our right. We had used up all of our ammunition. So, we picked up Yankee

cartridge boxes which strewed the ground. Their guns carried a ball about two

calibers smaller than ours, so we abandoned the slow method of drawing the

rammer to load. We tore the cartridge, placed it in the muzzle, and stamped the

breech on the ground; the weight of the bullet carried the cartridge home, so

we had to only cap and fire. It was almost like a repeating rifle.

There seemed to be no danger in our front as the Yanks had

continued their flight, we thought, all the way to the Chattahoochee. We fired

on that enemy battery so fast that it almost ceased firing. They turned a gun

on us but only fired once. Probably they were short of ammunition; for the

caissons were being rushed forward as fast as the horses could drag them, but

we had shot them down. We saw far in the distance a group of horsemen which we

took for a general and his staff. We all loaded, elevated our sights, dropped

behind a log, and took deliberate aim. In a moment, we saw them scampering

away.

We soon saw that the Yankees were returning and decided we

better get out. What had become of the balance of our forces we never did know.

We supposed many had gone to the rear with the prisoners and had forgotten to

return. With our guns all loaded, we started out the way we came in. On rising

a very steep hill in the woods, we saw 50 yards away that the woods were black

with Yankees. They had dropped in behind us, but with no idea that there was

danger from that direction as they were looking to their front. We all fired

into the thickest of them and fairly rolled down the steep hillside. Three of

us rushed down a ravine and after passing a spur went up another ravine.

Approaching a road down which General Walthall, our

division commander, and his staff were riding leisurely, I shouted to him,

telling him of the danger. One of his party came galloping saying “Go back to

the front, you stragglers!” With that, our lieutenant walked away demanding

that we should go back. I remarked that I’d speak to the General. In a few

words I told him that Stone’s Brigade hadn’t come up, that the Yanks were only

a little way down the road. On his expressing great doubt, saying “we have

certainly carried everything,” his smart Alec of an aide shouted off as he

galloped off, “I’ll see.” A short distance away he wheeled his horse and a

hundred bullets flew through the woods in his direction.

|

| General Edward C. Walthall |

In the middle of the road there was a brass cannon left by

someone. The General said, “You two men remain right here by this gun and when

I send you a force, pilot them to that hill you were on.” My companion was

Chunky Thompson, called that because he was not chunky; he was as slim as a

match and probably six feet and eight inches in height. We looked at the gun

and found it loaded but did not know how to shoot it. Finally, we thought we

knew and were determined that we’d fire it if the Yanks came. After a while the

25th Arkansas came with a very small number of men. Later another

bunch of probably 500 men had gathered. Then came a senior colonel as drunk as

could be. I’ll not mention his name because of subsequent history. He called

for the men General Walthall had left and wanted to know where the hill was. I

pointed the direction and suggested modestly that my companion and I with a few

others should act as skirmishers as there was no telling what changes had

occurred. He cursed me and said he was capable of running that business.

After a time of the wildest confusion, we were at the bottom

of the hill and I said, “There’s the hill, Colonel. I can’t tell you what’s up

top.” He ordered the charge. When within 20 or 30 steps of the top, a solid

blue line of Yankees rose up and I am sure half our men fell at the first

fire. I fired my gun and attempted to load it while lying down. It had been

fired so much that it had become clogged and the bullet hung halfway down the

barrel. Standing half bent, trying to ram the bullet home, the gun was shot out

of my hand, the stock literally torn to splinters. Fortunately, some of us

escaped because the Yanks, firing down the hill, overshot us. As I started down

the hill, I picked up a Yankee gun. Just then the colonel rode by capless as

fast as his horse could carry him. His drunkenness and foolhardiness had lost

the day and fully half his men. Getting back to our camp, the lieutenant said, “Wash,

General Walthall ought to promote you. But for you he would have been killed or

captured today.”

Of course, the common soldier didn’t hear much except by the grapevine and that was never trustworthy, but it was talked that the Peach Tree battle had been planned by Joe Johnston. The attack was to be made in double column, but the plan was changed, hence the disaster. Certain we were that with a fresh column to have followed up the drive, the results would have been a complete victory, for there was little fight in the enemy. I am sure many of them did not stop until the Chattahoochee was reached. Our men were cast down because of the removal of Joe Johnston, their beloved commander.

Source:

“In the Atlanta Campaign”

by Sergeant Washington Bryan Crumpton, Co. H, 37th Mississippi

Infantry, Confederate Veteran, October 1921, pgs. 381-382

Comments

Post a Comment