The 13th Ohio and the School of the Soldier

In the spring of 1861, 18-year-old Andrew Neff of Champaign County, Ohio signed his name to the rolls of Co. C of the 13th Ohio Volunteer Infantry. The next several months would educate the Ohioan on the ways of life in the army and the value of comradeship. “My comrades became as dear to me as my own beloved brother,” he wrote years after the war. “The story the old soldier now tells seems to the young as being manufactured for the occasion, but there is enough unwritten history that would easily fill volumes concerning the private soldier’s life.”

He arrived at

Camp Dennison in May of 1861 and his first impression was “it sure looks like

war.” The men, still dressed in their civilian clothes, soon were spending much

of their day on the drill field. “Military life and discipline now began in

earnest,” he noted. “Company, battalion, and regimental drill began. At first

it was sport, but we were not long in learning that it was not at all fun,

because if you think to drill from 4-6 hours a day is not about the hardest

work you’ve ever done, just try it for a month. There might be a lot said in

regards to our drill and discipline that transformed us green farmer boys into a

part of a great fighting machine of which each individual soldier became a

member.”

The regiment landed at Parkersburg, Virginia on July 3, 1861, and hearing some shots in the distance, “we began to think the war had begun. We had not received a round of ammunition yet, but it was not long until we were issued three rounds to the man so we began to feel like we would whip the whole Confederacy. To show how green we were and how little we knew about war, after we landed in Parkersburg and stood in line of battle, a fellow in a gray uniform came and made an inquiry for our commander. Our officers and this fellow went off a little ways and had a council of some sort. Someone started the story that the fellow in gray was a Rebel officer and they were planning where we would hold the battle. Some of the boys said, “Let’s shoot the son of a bitch!”

The regiment soon went into camp and were introduced the army way of living in the field.

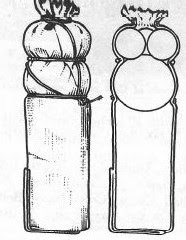

In Parkersburg, we drew our first tents and a

fully supply of cartridges. Our first tents were of the old Sibley style. To

describe them is to describe the Indian wigwam with a spider of three legs to

hold the center pole which was eight feet long and with the legs made the cone

of the tent 10-12 feet high. It had an opening at the top for the smoke to go

out, and our tent would accommodate 16-18 soldiers. When all in, each fellow

had as much room as the average sardine when packed and ready for shipping.

When the weather did not require a fire to stay warm, we used the center hole

for our guns and accoutrements. My bunkie was a little Irish boy named Mike

Walker who was about five feet tall while I was over six feet tall. It often

became necessary for me to make a typical Z of myself to get all of myself

under the tent at the same time while Mike could lay stretched out at his ease. Well, I did a lot of grumbling but as for Mike, God bless the memory of my damn

little pard, I never heard him complain of anything. He was always ready to

divide his last cracker with his fellow comrades.

We were now due

our knapsack, haversack, canteen, a change of drawers and shirts, and we

exchanged our citizen’s clothes for blue pants, a blouse, and became the Yankee

boy in blue. Besides this, we drew an old .69 caliber smoothbore musket and

belt with a bayonet and scabbard, a cartridge box large enough to hold 40 rounds,

and a cap box. In Parkersburg, we received a fully supply of cartridges, 40

rounds to the man, each 10 rounds done up in a package about 2-1/2 inches

square by one inch thick. In each package wrapped separate were 10 percussion caps.

Our cartridge boxes were made of very stiff leather about six inches square

with a heavy leather flap that was fastened at the bottom. Our ammunition was

well-protected from the rain. There was a tin box divided into four compartments

to fit snug into our cartridge box for the cartridges.

The cartridge was about two

inches long done up in strong paper. The ball was about the size of an ordinary

thimble. The paper that was around the cartridge was really a little sack just

large enough to go around the bullet which was hollowed out and filled with

stiff grease. The hollow was expected to expand at the discharge of the gun so

the ball would fit tighter into the grooves of the rifled barrel. The groove

was not straight down the barrel but cut in a circular fashion so when fired,

the ball would leave the barrel in a boring sort of motion that gave it move

velocity and penetrating force. The powder that was in the cartridge was about

three thimbles full and when the ball and powder were in the sack, it filled it

about two-thirds full. The remainder was calculated to act as a wad to be

pressed down solid on the powder when pressed home in the gun barrel making it

ready to fire.

One end of the cartridge was neatly folded and lapped over so when we were ordered to load, the first order was “handle cartridge,” which meant for us to reach to our box and take the cartridge between the thumb and finger. The next command was “tear cartridge” and that meant to put the neatly lapped end in our teeth and tear off the end. The next command was “charge cartridge” which meant to insert it into the gun barrel. Next was “ram cartridge.” All our motions were done in three commands which would be “load in three motions,” first handle, then tear, then charge the cartridge. Next was to ram in three motions, the first being to take hold of the ramrod and draw it halfway out, next full way, next turn ramrod and get ready to shove it home in three motions. Such was the old Scott drill mostly done in three motion order but in battle the order would be “fire at will” and that meant for every fellow to load and shoot as fast as he knew how regardless of discipline.

A few weeks later, Private Neff described his first night on picket duty.

A squad of a dozen under the

command of a corporal was taken about a mile out in front of camp and stationed

in line, across the road, and up the side of a mountain. It fell to my lot to

be the last boy to be placed on the extreme right of the line and way up on the

side of the mountain, in the center of a little cleared field stationed close

to a fence and the adjoining woods and fortunately behind a big fallen tree. I

was cautioned to keep a strict watch because there might be a bushwhacker who

would try and slip through our lines, or creep up and stab me to death. Then

the corporal left me alone and the next two hours were the longest that I ever

spent. The time for a guard to stand is two hours on and hour off. A corporal’s

guard consists of three men and the reliefs, as we called them, were divided

into three: first relief, second relief, and third relief. It had been three days

since we had been put through our arduous ordeal of marching and I was more

asleep than awake for in my imagination I could see some moving object just

over the rail fence and in the bush. It looked to me that men were creeping

through, half bent. The mountains in the country at that time were full of so

many wild animals, especially little black bears, and I believe it was the old

mother bear and her family because it would be hard to convince me that I did

not see anything. The night wore away and a glad boy was I, but we had been

scarcely called in before the bugle sounded “assembly” and we fell in. Before

the sun was scarcely up, we were again on the march over the mountains and

through the valleys toward the east, but to where, we privates did not know.

Once out on

the march, Private Neff started to realize what it meant to be a private

soldier. “As the regiment ahead was being assigned to their camp, it caused a

halt to the ones in the rear and the command was given “in place, rest,” which

meant to stand in a certain position. I was so tired that I stooped down to

rest more comfortably. Our tyrannical captain, Benjamin Runkle, ordered the

orderly sergeant to put me on extra duty. I there began to realize more fully

what a soldier’s life might be under a brutal officer. Our bugler Fred Russell

had only stepped to one side of the ranks and he, too, was put on for his

offense. We were both put on the same post and if it hadn’t been for his assistance,

I might have been shot for going to sleep while on guard.

|

| A lonely night on picket duty |

While on

picket that night, we discovered what are known as graybacks and a more

disgusted and surprised set of boys would be hard to find. As the old adage

goes, misery loves company, and it wasn’t long before we found out that we were

not the only ones that had more company than we wanted and an enemy we hated

worse than the other graybacks who carried a musket. We got through that night

somehow but the impression it left upon us was everlasting.

The news began to slowly leak out that there was an army of 25-30,000 Rebels in camp just a few miles ahead and we were going to have a battle. As for myself, I had been uneasy that the war would be over before I saw a battle and I think it was the feeling of the majority of the boys. But the idea of meeting 25,000 Rebels was not so pleasant to think of, but still we had our courage strung to the snapping point and did not have to wait long until we had a chance to let it out a turn or so.

The 13th Ohio saw its first battle on September 10, 1861, at the Battle of Carnifex Ferry, Virginia while under the command of General William S. Rosecrans. It was, as Neff remembers it, a confusing introduction to the mysteries of battle.

We could hear

a shot now and then and as we advanced these shots became three, then four,

then quite often, as we were crowding the enemy pickets backwards. Our army was

now composed of about 8,000 men and when we got into line of battle with our

two pieces of brass 12-pdrs, we thought we could lick the whole Confederacy. At

about 3 p.m., we began to move forward in our battle line over the fields and

gullies. Our advance was not very fast, but the musket shots became more

frequent and occasionally an artillery shot would get the boys to yelling. A

way off in the woods we got the answer of the Johnnies called the Rebel yell. We

began to believe there was more in war than blow or wind.

Our lines were advancing

cautiously through the timber until we came to an open patch of ground and then

we had a good view of what was before us: a fort of considerable magnitude with

breastworks on the outside as far as we could see and lined with men. Back on

top of the hill was the fort and where they had their artillery planted. To a

green boy not three months our of the cornfield, thoughts of home and elsewhere

were uppermost in our minds. But, as we were commanded to lay down, it was

difficult for the Johnnies to see or hit us as it was for us to hit them. In a

short amount of time, the scare began to wear off with the din of thousands of

muskets and the boom of cannons until night with its shades drawing on and

darkness became a welcome visitor.

Our army began to make charges

and a charge on these breastworks which made the Rebels fall back to their

stronger fort. Night and darkness of the woods was against us, especially where

our regiment was as we ran into another regiment, the 10th Indiana.

They mistook us for the Rebels and fired on us, killing several of our boys

before they knew who we were. We got things straightened out and were soon

ready to make a general charge on their works in the morning.

We could build no fires to make coffee or roast our sowbelly and had to eat a cold supper of hardtack and soon lay down as best we could. About midnight it began to rain and there was no more sleep, but I lay there with thoughts of home and the girl I left behind. Already several of the boys had been killed and wounded which filled many of us with very sober thoughts and we all knew that to charge that fort meant certain death to many, and anyone might be among that number. We looked toward daylight with more anxiety than I can tell it, but before daylight came, the word was passed down the line that the Rebels had evacuated their fort. That was the best news we had heard for a long time and the shouting and noise we made was plenty. The Johnnies were as anxious to get as we were to have them go.

Source:

Memoir of Private Andrew Neff Young, Co. C, 13th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Robert Van Dorn Collection

This is a good one. Thanks.

ReplyDelete