The Storm of Blood That is Sure to Reign: At Antietam with the 2nd North Carolina

In part 3 of this series, Lieutenant John Calvin Gorman of the 2nd North Carolina describes his participation in the Battle of Antietam on September 17, 1862. General George B. Anderson’s all-North Carolina brigade consisting of the 2nd, 4th, 14th, and 30th regiments took a position along the Sunken Road that morning and fought for hours against repeated Federal assaults. The casualties were horrific, as Gorman’s regiment lost two-thirds of the 300 men that marched into battle that day, and Gorman himself was wounded twice, once in the head and a second time in the foot.

The

combat in this sector of the field was incredibly violent and intense. “The air

is full of lead, and many are shot as they are aiming at the enemy, and the

groans of the wounded are heard amid the roar of musketry,” Gorman remembered. “Colonel

Charles Tew was killed about 11 o’clock, a Minie ball penetrating his brain. It

is certain death to leave the road wounded as the balls fly so thick over us. We

hear reinforcements coming up behind us, but the fire is so hot they were not

able to come to our succor and were forced to fall back.”

Gorman’s letter, written to his wife and mother while he was convalescing from his wounds in Charlestown, Virginia just four days after the battle, was originally published in both the October 1, 1862, edition of the Raleigh Semi-Weekly Standard and the October 6, 1862, edition of the Spirit of the Age, also published in Raleigh.

To read part 1, click here.

To read part 2, click here.

September 21, 1862

The

enemy was wary and though making demonstrations, did not dare to cross Antietam

creek which remained the dividing line between us until Wednesday morning. We

threw out skirmishers to the creek bank, placed our artillery in position, and

though desultory fighting between the pickets was continuous and not an hour

passed but the booming of cannon and the whiz of shell grated on the ear, we

ate, slept, and stood in line of battle through the long hours of Monday night,

Tuesday, and Tuesday night.

On Tuesday,

one division of Jackson’s victorious corps joined us. They had, while we were

fighting on South Mountain on Sunday, been busily fighting near Harper’s Ferry,

and succeeded on Monday evening in capturing the whole garrison of 13,000

Yankees, 15,000 stand of arms, and about 90 of the most improved pieces of

field artillery together with a large lot of ammunition, clothing, shoes,

horses, and wagons. I have seen all the captured articles myself.

|

| A U.S. Model 1861 Springfield rifle lockplate recovered from Antietam. (The Horse Soldier of Gettysburg) |

Our

battle line was now formed anew. Jackson’s troops were put on the right, D.H.

Hill in the center, and Longstreet’s on the left facing the creek with their

backs towards the Potomac. All day long Tuesday we could see heavy columns of

Yankees arriving in front of our lines and I felt that the crisis was near.

At

daylight on Wednesday morning, we were awakened by heavy artillery and musket

firing on our left and each man was ordered to his place. Desperate and heavy

does it rolls from the left and the sound seems to come nearer. Soon we see the

wounded coming limping towards us, and they say the enemy has attacked our left

flank in heavy force and our men are falling back. Look at that cloud of dust!

Our artillery is retreating and while we are straining our eyes in the

direction of the retreating mass of men that are just emerging in view, away

over the open hills on our left.

A

galloping courier arrives and directs General Hill to change his front to the

left. Quickly we are faced to the left, marching through a growing field of

corn, and then filed to the left in a long lane that runs parallel to our left

flank. Our whole division take position in the lane: Ripley on the extreme

left, Garland’s next, Rodes’ next, and Anderson’s on the right. Away goes

Longstreet’s retreating line to our rear. In a few moments I could see the advancing

line of Yankees. Three heavy columns are approaching us, extending to the right

and left as far as we can see, each column about 100 yards behind the other, and

the nearest scarce 400 yards distant. To oppose this was Hill’s weak little

division, scarce one-fourth as large and my very heart sank within me as I

heard General Anderson say to one of his aides to hurry to the rear and tell

General Hill for God’s sake send us reinforcements as it was hopeless to

contend against the approaching columns.

It was

now about 8 o’clock. The battle had begun also on the right of our first

position and Jackson was hotly engaged. Sharpshooters were sent about 50 yards

to the front of us, and our lie ordered to lie down in the lane and hold their

fire till the enemy was close to us. I stood near Colonel Tew on the crest of a

hill in front of our position and gazed with tumultuous emotion over the fast-approaching

line. Our little corps seemed doomed to destruction, but not an eye flinched,

nor a nerve quivered, and you could observe the battle light of determination

on every countenance. I then felt sure that we would do honor to our noble old

state that day though we would not live to see it again.

On moved

the columns until I could distinguish the stars on their flaunting banners, see

the mounted officers, and hear their words of command. Just then, a Yankee

horseman waved his hat at us, and Colonel Tew returned the compliment. It was

the last I saw of the colonel. Our skirmishers began to fire on the advancing

line, and we returned to ours. Slowly they approached up the hill and slowly

our skirmishers retired before them, firing as they come. Our skirmishers are

ordered to come into the line. Here they are, right before us, scarce 50 yards

off, but as if with one feeling our whole line pours a deadly volley into their

ranks. They drop, reel, stagger, and back their first lines go beyond the crest

of the hill. Our men reload and wait for them to again approach, while the

first column of the enemy meets the second, they rally, and move forward again.

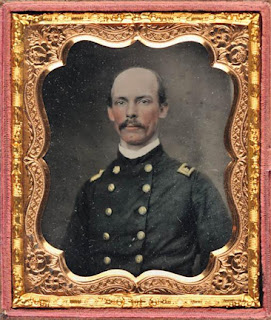

|

| Colonel Charles C. Tew, 2nd North Carolina Killed in action |

They

meet with the same reception and back again they go to come back when met by their

third line. Here they all come. You can see their mounted riders cheering them

on and with a sickly “huzzah” they again approach us at a charge, but another

volley sends their whole line reeling back. They then approach the top of the

hill cautiously, and lying down, we pour into each other one continuous shower

of leaden hail for four long mortal hours. The whole air resounds with the din

of arms. Musket, rifle, cannon, and shell pour forth an avalanche of lead and

iron.

Our men

are protected by about six or eight inches of the wear of the road, but that is

great protection, and they fire cautiously and are apparently as cool as if

shooting at squirrels, taking sure aim every fire. The protection, however, is

not sufficient. The air is full of lead, and many are shot as they are aiming

at the enemy, and the groans of the wounded are heard amid the roar of

musketry. Colonel Tew was killed about 11 o’clock, a Minie ball penetrating his

brain. It is certain death to leave the road wounded as the balls fly so thick

over us. We hear reinforcements coming up behind us, but the fire is so hot

they were not able to come to our succor and were forced to fall back.

Our

numbers are perceptibly reduced by deaths and wounds and our fire slackens,

while the enemy has succeeded in planting a battery that rakes the roads and

sends many to eternity at every discharge. Our left has given away and the

enemy has already crossed the line in our rear. At last, the order is given to

fall back and the few that remain uninjured fall sullenly back. The enemy,

however, has been so badly punished that they are not able to follow us immediately.

We rally behind a stone fence and await their approach, the whole division

hardly making a respectable regiment. Reinforcements arrive, the enemy

approaches, but fall back in disorder before a fire from behind the wall that

fairly melted their ranks. Their retreat is followed up by the fresh troops of

A.P. Hill who have just arrived.

When

night sets in, the enemy is whipped three miles from the battlefield on the

left, while the receding fire that blazes horribly from the right indicates

that on the right, too, the enemy are sullenly retreating before the invincible

forces of Jackson. That day is ours but dearly won. Six to eight thousands of

our brave boys lay around dead or wounded in that day’s fray, while the ground

is made blue by Yankee carcasses. They left fully 4,000 dead on the field and

their wounded must be immense. Our regiment brought only 100 out of the fight,

just one-third it carried in, while other regiments suffered worse.

The next

morning, the Yankees sent in a flag asking permission to bury their dead, and

all that day was devoted to that purpose and to taking care of the wounded who

are now hospitalized at Sharpsburg, Harper’s Ferry, Charlestown, Winchester,

and throughout the country on the Virginia side of the Potomac. Each army was

so disorganized that neither was able to make another offensive move.

On

Friday the 19th, our army crossed the river into Virginia and

encamped in the woods near Shepherdstown. The enemy took the movement as a

retreat and on Saturday morning undertook to cross at the same ford but were

met by our forces and driven pell-mell across the river with fearful slaughter.

Our loss was slight. Our army has again crossed into Maryland and occupy the

same places they did before the battles, while Stuart with his cavalry is at

Hagerstown near the Pennsylvania line. I do not know what will happen next.

|

| A chunk of a tree from Antietam holding at least four musket balls. (Heritage Auctions) |

Now, as

I have given you an account of the battles, I will give an account of myself. I

do not know all that are killed and wounded in the regiment, nor even my own

company. I know that Colonel Tew is killed, and Captain Howard taken prisoner.

Captain Hunt of Co. I was wounded and taken prisoner. Lieutenant Applewhite of

Ci. D was wounded in the arm, and I hear there are only three officers with the

regiment. I was slightly wounded on the head and in the right foot about 1 o’clock

by a bursting shell. I had no bones broken. I was able to get off the field myself

and did so without being hit again. Many others tried it, but I am the only one

I know of who attempted to leave the field wounded that was not shot again.

I went

to the rear, had my wounds dressed, hired a horse, and knowing the vicinity of

the battlefield would be crowded with wounded, came to this place. There are

about 400 wounded in the hospitals here and they are treated as well as if they

were at home. Every woman in the town is a devoted Southron and they all vie

with each other in their kindness to the wounded. I am so fortunate as to be

able to secure quarters with a rich Presbyterian family, where every lady about

the house does as if she could not do enough for me. They want to wait on me

too much. There are three other wounded officers in the office with me, and I

am not able to eat the good things that are showered upon me at all hours of

the day.

I am in

perfect clover and stow away large quantities of luscious grapes, apples,

peaches, pears, while preserves, cakes, and pies lie untasted around me. I

shall be loathe to go back again to green corn, badly cooked flour bread, and

fat middling. I would come home and see you, but my wounds are not respectable

enough to ask for a furlough; besides, it is 100 miles to where a railroad is

running and what few men I have left are without a single officer. For three or

four days before the battles we suffered much. We had to lie out in line of

battle without blankets and take the sun, rain, and dew, and I never got a

mouthful to eat but green corn from Saturday night till Wednesday night.

Notwithstanding all that, I enjoyed excellent health.

Source:

Letters from First Lieutenant

John Calvin Gorman, Co. B, 2nd North Carolina Infantry, Spirit of

the Age (North Carolina), October 6, 1862, pg. 3

Comments

Post a Comment