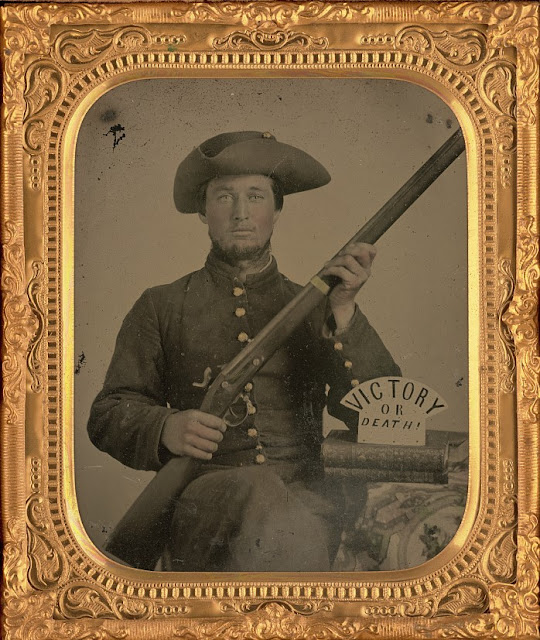

Old Blucher Thompson Charges the Round Forest at Stones River

After Major John Clarke Thompson of the 44th Mississippi lost his life on the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga, he was remembered in many ways. His immediate commander Colonel J.H. Sharp called Thompson “fearless among the fearless” while General Patton Anderson recalled Thompson as a “man of education and position at home, of an age far beyond that prescribed by the laws of the land for involuntary service.”

Thompson, born in 1805 in

Georgia, had by 1860 moved near Hernando in DeSoto County, Mississippi where he

had built up a substantial plantation and developed a reputation as an astute

attorney. In the secession crisis that followed Abraham Lincoln’s election in

November of that year, Thompson “did not hesitate to avow himself a

secessionist” and following the outbreak of war, volunteered as a private

soldier in Co. D of Blythe’s Mississippi regiment along with his eldest son

Fleming. “When asked why he enlisted at his age (56), he replied that he had

talked and voted for secession and felt he ought to fight for the cause,” one

of his comrades later remembered.

Due to his advanced age, the men

took to calling John “Judge” Thompson. Later his bravery would earn him the

more enduring nickname of “Blucher” Thompson.

Blythe’s Mississippians took

part in the fighting at Belmont and Shiloh, losing heavily in the latter battle

where Thompson was also severely wounded. In the reorganization of the regiment

which followed Shiloh, Thompson was unanimously elected captain of Co. D and

then selected (again by election) to become the major of the regiment. He

proved a popular officer even though he was more than twice the age of most of

his companions. “As an officer he ruled without harshness and obeyed without

murmuring and whether on the march, in the camp, or upon the field of battle,

he ever had a hand to give and a heart to feel for the distressed,” his

obituary stated.

Thompson’s bravery on the field

was legendary, and his men took to calling him “Blucher” Thompson. “He was the

very impersonation of courage and daring,” his obituary continued. One thing

that Thompson was not was a schooled soldier; one of his men later wrote that Thompson

was “as brave a man as ever lived but whose brain had been shriveled by age and

bust-head; he was nearly 70 years of age and had drank all his life.” While the

soldier was off a bit on Thompson’s age, it was noted on Thompson’s August 1863

efficiency report that the inspector felt that Thompson was “incompetent and inefficient

but gallant and deserving.”

A good case in point that illustrates

this occurred on December 31, 1862, when Thompson led his regiment into action at

Stones River. One of his veterans, writing an article for the Alabama

Soldier newspaper in 1892, provided the following description of how this

attack went down.

It’s worth noting that a few

days before, the Blythe regiment had been quarantined due to a smallpox

outbreak. While still in quarantine, the regiment had been ordered on December

26th to turn in its weapons which were distributed to the other

regiments of the brigade. But on the 28th, the decision was made to

put Blythe’s men back on active duty and they “were furnished with refuse guns

that had been turned over to the brigade ordnance officer. Some of the guns

being bent, some without locks, some when cocked could not be pulled down, some

whose hammers had to be carried in the men’s pockets until time to commence

firing, while others were so fouled as to render them impossible to ram home

the cartridge,” Major Thompson later reported. Many of the guns lacked ramrods

and only one had a bayonet. “Even of these poor arms there was not a

sufficiency and after every exertion on my part to procure arms, only one half

of the regiment moved out with no resemblance to a gun than such sticks as they

could gather.”

Thus armed, Blythe’s regiment

(later renamed the 44th Mississippi) as part of General James

Chalmers’ brigade went into the fight along the Nashville Pike late in the

morning of the 31st and by early afternoon the Mississippians were

pinned down by Federal artillery fire emanating from the Round Forest. Our soldier correspondent takes up the story:

“At a certain point in the

battle, the grape from one of the Federal batteries began to whistling with

disgusting frequency and in disturbing proximity to the boys and the gallant

major,” the soldier wrote. “He turned to his adjutant Charlie Odom and inquired

where they came from. Being told that they came from a Yankee battery just upon

a wooded knoll not far away, he inquired in some excitement, “Why in the hell

don’t they capture the damned thing?” The reply being that “the little thing

can’t be did” as several brigades had already been torn to pieces in the effort

and all had failed. The old hero’s face flushed and raising himself in his

stirrups, he yelled, “The Blythe can take it. Attention! Form line, and forward

charge!”

“The men obeyed as they had

always done until they and the major found themselves in an old cotton field 100

yards from the battery exposed to such a hail of grape and canister as they had

never seen or felt before,” our correspondent continued. “Old Blucher saw the

folly of any further movement in that direction, called a halt, and ordered the

men to lay down.”

“Having got there, the question

was how to get away,” the soldier explained. “The men were being killed by the score.

The ridges afforded scarcely any protection and to remain there long meant the

utter destruction of the command. In vain, the old hero searched his memory for

the command by which a well-drilled regiment could be taken out of such a

desperate pickle.”

“At last, in despair, he turned

to the adjutant and exclaimed, “Charlie, damn the military evolutions, I could

never think of the word of command at the right time. Then, turning to the

regiment as they lay sprawled on the ground, he shouted, “About face men and

run like hell or you’ll all be killed in a minute!” This order was obeyed like

all the others, without comment or criticism, and to his credit let it be said

as in every other retreat the Blythe regiment made while he lived, the brave

old Major Thompson brought up the rear.”

Major Thompson survived Stones

River but met his end nine months later on Snodgrass Hill. “At Chickamauga, his

regiment as well as his brigade was ordered to retreat. Not hearing this order

(being in the advance of the line), Thompson supposed they were showing the

white feather and immediately began rallying them with exclamations of surprise

and mortification when a bullet passed through his head, killing him instantly,”

his obituary noted.

“That night, a squad of his devoted comrades, of which I was one, carried the brave old body to the rear,” W.H. Lee of the 44th Mississippi wrote in 1905. “We made a rude coffin of boards torn from Lee & Gordon’s Mill and reverently committed his body to rest with a few words from our chaplain. Peace to his ashes; he has surely gone to Valhalla." And so ended the military career of "Old Blucher" Thompson.

Sources:

“Battle of Murfreesborough,” Western Veteran (Kansas), October 12, 1892, pg. 7

“Major John C. Thompson of Mississippi,” by W.H. Lee, 44th Mississippi, Confederate Veteran, November 1908, pg. 585

Major John C. Thompson, Combined Military Service Record, Fold3.com

Ancestry.com entry for John Clarke Thompson (1805-1863)

Obituary for Major John C. Thompson, Memphis Daily Appeal (Tennessee), December 7, 1863, pg. 2

To learn more about the Stones River campaign, be sure to check out my new book "Hell by the Acre: A Narrative History of the Stones River Campaign" available now from Savas Beatie.

Comments

Post a Comment