An act of practical Christianity

After losing both of his legs to amputation at Second Bull Run, Corporal James Tanner of the 87th New York recalled a striking instance of what he called “practical Christianity,” as he lay amongst the wounded and the dying.

The men had gone without food or water for several days and

one mortally wounded man, whose name is lost to history, crawled in agony from

the tent to a nearby apple tree. Stuffing a half dozen worm-eaten apples that

had fallen to the ground into his coat pocket, he crawled back to the tent and gave

them to his comrades. It was his final act. Within moments, the man was dead.

“I have often thought that in his last act he exhibited so

much of what I consider the purely Christ-like attribute,” Tanner recalled. “What

that man’s past life had been, I know not. It may have been wild and his speech

may have been rough. I know that he was unkempt, unshaven, his clothes soiled

with dirt and stained with blood. Not a picture that you would welcome at first

sight into your parlor or to your dinner table.” But in his final moments, he

gave a striking example of Christ’s injunction to “love your neighbor.”

Corporal Tanner would be discharged for his wounds October 15, 1862, at Fairfax Seminary but after being fitted with a pair of prostheses, went to work for the War Department as a clerk for Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. The night President Lincoln was assassinated, Tanner was summoned to Lincoln's bedside by Stanton and took shorthand notes of what occurred, providing the most comprehensive record of the events of Lincoln's death. After the war, he entered the bar in his home state of New York and became deeply involved with the Grand Army of the Republic, serving as New York State commander from 1876-1878 and national commander in 1905. His account first appeared in Wilbur Hinman’s 1892 tome Camp and Field: Sketches of Army Life Written by Those Who Followed The Flag, ’61-’65.

I was in the 87th New York; we had passed through

the campaign of the Peninsula and came from there to join Pope. We had several

days of intermittent fighting around Manassas, Bristow, and Catlett’s Station

until on the 30th of August we were on the field of Second Bull Run.

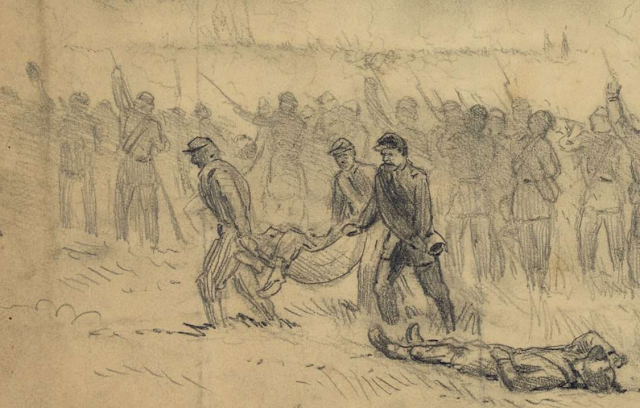

Along the afternoon of that day, I was struck with a piece of

shell which necessitated the amputation of both of my lower limbs. The

operation was performed under fire. My comrades, placing me upon a stretcher,

started to carry me off the field. The fortunes of war were against us and it

was impossible for them to get me away. They carried me into a house and filled

my canteen with water, then bade me goodbye and barely escaped being taken prisoner.

With about 170 others, I lay in that house for 3 or 4 days.

Some were lying in the yards. It was on the fourth day that I, with some others,

were moved out into the rear and placed into a little tent. Six men lay in the

tent and the six men had seven legs amputated. We were lying on a rough board

floor with not a rag of clothing on; a thin rubber blanket lay between our

bruised and bleeding bodies and the hard floor and a single blanket covered our

nakedness. I was especially favored by reason of the fact that I had a piece of

board about as long as your arm set up slanting as my pillow.

|

| Corporal James Tanner Co. C, 87th New York |

We were prisoners of war. Our captors had next to nothing to

eat themselves and we, if possible, had less than they. The Virginia sun poured

down its intense heat. Hunger, thirst, flies, maggots, and all the horrible

accompaniments were there. A very few men had been left behind to try and take

some sort of care of us, but their numbers were sadly deficient. We lay there

one day moaning for water and there was none to bring it to us.

Just at the entrance of our tent lay a poor fellow terribly

wounded on the left side. He was a stranger to us and we to him, but it has

always seemed to me since that the man was a descendant of the most gallant

knights of old. He heard our moans. He could not bring us water but looking

over the greensward and out beyond under the trees, he saw there were some

worm-eaten apples that had dropped from the branches overhead.

Every movement must have been agony unendurable to that man,

yet he clutched at the grass and dragged himself until at last he was in reach

of the apples. Picking them from the ground, he placed them in the pocket of

his blouse and then, rolling himself around to keep his sound side on the

grass, dragged himself back until he lay again at the entrance of our tent. He

reached out the apples one by one, and as I lay nearest the entrance, I took

them from his hand and passed them along until each one of my unfortunate

comrades had one.

I had just set my teeth in the last one he had handed me; it

tasted sweeter to me than the nectar of the gods. I heard an agonized moan on

my right and turning quickly I saw this good Samaritan with his hands clutching,

his eyes rolling. He was in the agonies of death. A moment more and it was all

over for him on this side of the great river. That is all. I never even knew

his name. In some home they may mourn him yet as missing. Perhaps his bones

have been gathered up and in one of cemeteries they are interred under the

designation “unknown.”

What that man’s past life had been, I know not. It may have been wild and his speech may have been rough. I know that he was unkempt, unshaven, his clothes soiled with dirt and stained with blood. Not a picture that you would welcome at first sight into your parlor or to your dinner table. But this I have often thought that in his last act he exhibited so much of what I consider the purely Christ-like attribute that in the day when you and I shall stand before the just judge, to be judged for what we have been and not for what we may have intended to be, I would much rather take my chances in the place of a man who had so large an idea of practical Christianity than in the place of many more pretentious persons I am acquainted with.

Source:

“Corporal

Tanner’s Hard Luck: Tells How he Lost Both Feet at the Second Battle of Bull

Run,” Corporal James Tanner, Co. C, 87th New York Volunteer

Infantry, from Wilbur F. Hinman’s Camp and Field: Sketches of Army Life

Written by Those Who Followed The Flag, ’61-’65. Cleveland: N.G. Hamilton

Co., 1892, pgs. 316-318

Comments

Post a Comment