Winged at the Outset: Wilbur Hinman’s Experiences at Chickamauga

First Lieutenant Wilbur F. Hinman of the 65th Ohio, who later gained much notoriety for his books Si Klegg & His Pard and The Story of the Sherman Brigade, penned this reminiscence of his experiences being wounded at Chickamauga. This story was included in his 1892 anthology Camp and Field: Sketches of Army Life Written by Those Who Followed The Flag, ’61-’65.

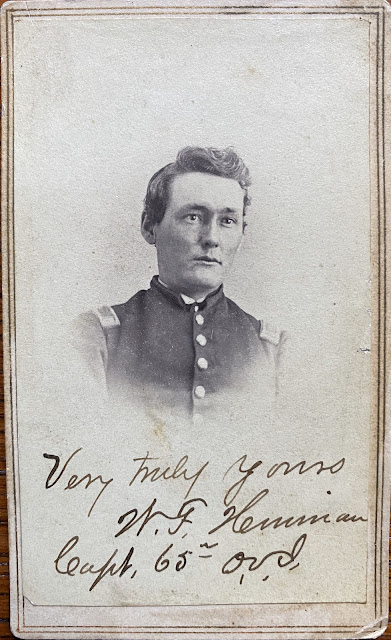

|

| Captain Wilbur Hinman, Co. E, 65th Ohio Volunteer Infantry (Gary Milligan Collection) |

We were part of Wood’s division of

Crittenden’s 21st Army Corps. For a week before the battle, we bivouacked

along the banks of Chickamauga Creek at Lee & Gordon’s Mill. There was

constant skirmishing with the enemy and a battle was expected daily. The

movements of the Confederates on September 18th left no doubt of

their intention to attack. Bragg knew that Rosecrans’ army was then widely

scattered and his purpose was to attack the corps in detail and overwhelm each

in turn before it could receive succor. It was only by extraordinary efforts

that Rosecrans succeeded in getting his forces together before Bragg delivered

battle. A delay of one more day would have been fatal.

During the afternoon and evening of

the 18th there was heavy fighting at some points and every man felt

intuitively that the next day would be a bloody one. There was little sleep in

the army that night. All through the slowly dragging hours, divisions and

brigades were moving here and there to take the positions assigned them. We

remained all night at the mill.

Memory recalls that a group of 16 officers of the 65th

Ohio sat under a tree the next morning and ate breakfast. There were anxious

hearts and sober faces. We wondered who of us would be stricken down in the

battle for we knew that some must fall. Truly the missiles of war did make sad

havoc with that little company of officers; 36 hours later, three of them were

dead and seven were wounded. Eighteen years later I stood again upon that very

spot and how the events of the old days came up before me.

Bragg expected to deliver battle on the 18th and

it was fortunate for the Union army that he was unable to do so. The time thus

gained was of priceless value, enabling Rosecrans to affect the concentration

of his army. This was only accomplished by an all-night march of several

divisions. It is not my purpose to even attempt to give a history of the battle

but only a narrative of personal experiences. The 65th Ohio was in

the thickest of the fight and suffered its full share of loss in killed and

wounded.

The battle opened on the morning of Saturday, September 19, 1863,

in Thomas’s front. We lay at Lee & Gordon’s Mill until perhaps 11 o’clock,

ready to move upon the instant. There was heavy and continuous firing some

distance away and we knew ere long we would be called. A staff officer dashed

up and delivered an order. Colonel Harker, commanding the brigade, sprang into

the saddle and the command “Fall in,” was instantly given. Away to the left we

went at the double quick.

We marched two miles along the road

through clouds of dust which settled on the perspiring faces until one could

scarcely recognize his nearest comrade. “By file, right!” and leaving the road

we entered the woods. We had gone but a short distance when we began to hear

the angry hiss of bullets. They came from a direction which indicated that we

were in the uncomfortable positions of being enfiladed; the firing was squarely

from our left flank. Lieutenant Colonel Horatio Whitbeck ordered, “Change front

forward on the tenth company!” The movement was as perfectly executed as if on

a drill ground under a galling fire, before which men were falling every

instant. Then came the commands, “Lie down! Fire at will!” The work was hot and

furious.

I cannot tell how much time elapsed

(it seemed to me hardly five minutes) when a bullet plowed a furrow across my

body in front and zipped through my right arm at the elbow. The ball had lost

none of its force for we were at close quarters and went like a streak of

lightning. The first sensation I experienced was like of a smart blow with a

stick. My sword tumbled to the ground and my arm fell powerless at my side.

Blood flowed freely and I felt the necessity of getting back to the rear and

having my wound dressed. For that day at least, I would be no good.

One of the boys tore a strip from

the tail of his shirt, twisted it into a string and tied it tightly around my

arm to check the bleeding. It had the desired effect and directing the orderly

sergeant to take care of the company, I started back. My legs were all right

and I made pretty good time until I was out of range. As long as I could be of

no further service until I had repaired damages, I felt that I didn’t want to

get hit again if I could avoid it.

The woods were full of wounded men,

streaming to the rear. Some fell, weak and exhausted, and were borne away upon

stretchers. It was a scene to move the hardest heart. I offered assistance to a

soldier belonging to another regiment of our brigade who had been shot through

leg. Leaning upon my left shoulder, and using his musket as a crutch, he

hobbled along and together we made our way to the field hospital of our

division more than a mile in rear of the line of battle.

|

| "The woods were full of wounded men, streaming to the rear. Some fell, weak and exhausted, and were borne away upon stretchers." |

The picture there was harrowing in

the extreme. Several great hospital tents were filled with men maimed and

mangled by bullets or shells. Outside upon the ground were hundred more lying

on blankets. Surgeons and nurses were busy everywhere examining wounds and

doing whatever each case required. In one of the tents was an amputating table

where, with sleeves rolled up and saw in hand, the surgeons engaged in their

horrid work. Outside lay a score of legs and arms that had been taken off. The

scene brought tears that I could not repress.

I did not know how badly I had been

hurt. I remember that all the way back from the front I was wondering whether I

would lose my arm. At length, I found good old Dr. Todd who had formerly been

our regimental surgeon. “Hello, lieutenant, they’ve winged you, too, have

they?” was his cheery greeting. As soon as he had finished one or two more

serious cases which he had on hand, he took hold of me. He cut away the torn

and bloody sleeve and with a touch as gentle was a woman’s examined the wound.

“We’ll save that arm all right,” he said, and his words gave me immeasurable

relief.

He pushed a probe through to expel

any fragments of the cloth that might have lodged in the wound and this gave me

vastly more pain than did the bullet. Then he stanched the blood, wrapped the

arm with bandages, put it in a sling, then gave his attention to another.

All the afternoon and far into the

night the sufferers continued to come in from the field of conflict. There was

work for everybody who was able to do anything. Many whose wounds were

comparatively slight gave food and water to the helpless ones, and in every

possible way ministered to their comfort. No human feeling is stronger than the

sympathy of a soldier for a brave comrade who has been stricken down in battle.

For not a few of those poor fellows, it was their last night on earth. Not less

than two score at that division hospital never saw the sunlight again.

|

| Lt. Col. Horatio Whitbeck 65th O.V.I. |

During the forenoon of the next day,

when disaster befell the right wing of the Union army, a report reached our

hospital that a body of Rebel cavalry was swooping down upon it. What followed

was very much like a stampede. All the ambulances at hand were hastily filled

with such of the wounded as could be moved and they were started for

Chattanooga. Among those who in this way escaped the clutches of the enemy was

Lieutenant Colonel Whitbeck of the 65th Ohio who had been grievously

wounded the day before about the time I was hit. All of the wounded who were

able to walk joined in the general rush for Chattanooga. I was one of these

for, like others, I had a mortal dread of being a prisoner.

The surgeons and many of the

non-combatants who were serving as nurses, remained at their posts of duty and

were captured when a few minutes after our hasty departure, the Rebel troops

surrounded the hospital. Part of the wounded were exchanged a few days later.

The rest were removed to Southern prisons where more than half of them died.

We scampered along as best we could

to get out of the way of the Johnnies. The road was filled with a confused mass

of wagons, ambulances, wounded men, and demoralized stragglers from the routed

divisions of the right wing. We feared that the whole army was driven and the

day was lost. We could still hear heavy firing, however, indicating that

somebody was still able to fight.

That night at Chattanooga we learned that grand old “Pap” Thomas with his own and Crittenden’s corps, and fragments of McCook’s, had stood firm as a rock, repelling all the fierce assaults of the enemy upon him. A few days at Chattanooga and then a long train of ambulances conveyed several hundred of the wounded to Bridgeport whence we went in cattle cars to Nashville. There I was furloughed and spent two months at home, nursing my wounded arm and telling the story of the battle to the people of the village in which I lived. Our company had fared badly. Four of its members had been killed and four were captured, not one of whom lived to return top Berea.

"Paying Our Road Tax: Building a Road Through Hall's Gap"

"Meeting Old Rosey: General Rosecrans Reviews His New Command"

"All the Fury of Demons: The 65th Ohio at Stones River"

"Breaking the Macon & Western Railroad"

Source:

“A

Chickamauga Experience,” First Lieutenant Wilbur F. Hinman, Co. E, 65th

Ohio Volunteer Infantry, from Wilbur F. Hinman’s Camp and Field: Sketches of

Army Life Written by Those Who Followed The Flag, ’61-’65. Cleveland: N.G.

Hamilton Co., 1892, pgs. 138-140

Comments

Post a Comment