Paying Our Road Tax: Building a Road Through Hall's Gap

In the aftermath of the Federal victory at Mill Springs in January 1862, Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood's brigade marched from Lebanon, Kentucky to Hall's Gap near Stanford, Kentucky. Upon arriving, the four regiments of the brigade were given a seemingly simple task: build a corduroy road through Hall's Gap to Somerset, Kentucky, where General George H. Thomas' division was waiting for supplies. What started out as a simple construction job degenerated into a tedious, frustrating, fruitless, and even deadly proposition. The situation became so bad that the men referred to Hall's Gap as Hell's Gap. Indeed, Wilbur Hinman of the 65th Ohio reported that "our two week's stay at Hall's Gap cost us as many men who died or were disabled by disease as we lost at either Stones River or Chickamauga."

A combination of rainy weather and heavy traffic turned the Somerset road into a quagmire, and the need to upgrade the road became abundantly evident after General Thomas' division passed through the area in mid-January. Orderly Sergeant William Buchanan of Co. B of the 16th Ohio Infantry was among the brigades which followed Thomas' division into Somerset. "We had heard of the mud country and the bad roads we would have to travel after leaving the pike, but our imagination failed to picture such bad roads as we encountered that day," he reported on January 16th. "While plodding through the mud and water, some men were laughing and singing, others cursing the Rebels as the cause of their troubles, some swore that if they were home again it would be a pretty story that would get them to enlist. Some plodded along thinking much but saying nothing. Here and there you might see a weary, wet, and mud-spattered fellow by the roadside leaning up against a fence looking as though he would sell out cheap."

That same afternoon, General Thomas J. Wood, headquartered at Bardstown, received an order from General Don Carlos Buell through his chief of staff Colonel James B. Fry to put the Danville to Somerset road "in good order" and provided Wood with 1,000 axes, 1,000 picks, 500 shovels, and 500 spades to corduroy the road "not less than 16 feet wide." General Thomas was likewise ordered to work his way north and corduroy the road in the opposite direction. The pike stopped at Stanford but a rough woodland road carried the road over Hall's Gap into Somerset, an approximately 35-mile stretch of road that in its present condition could not be used by the army's heavy supply wagons, especially in the wet season. "The supply of the troops depends on the early completion of the road and it is hoped it will not occupy more than ten days."

Wood gathered up the four regiments of his brigade (the 51st Indiana, 19th Kentucky, 64th, and 65th Ohio) and marched through Lebanon into Stanford arriving on the 24th. Private Christian M. Gowing of the 64th Ohio commented that the regiment received a cold welcome in Stanford as "secession had taken rather a strong hold on the inhabitants and we did not meet the good old smiles of Uncle Sam, but wended our way through in silence and marched on for Hall's Gap" seven miles further south. Hall's Gap, featuring two knobs along the Cumberland Mountain range, was noted by one soldier as the place "where Hall fought the Indians at the time of the settlement of the state. It is a rather remarkable place for soldiers to encamp."

The following morning, the men of the 51st Indiana and the two Ohio regiments were called into ranks and given their orders. "We were told that for a while, 'spades were trumps, and we would have the job of building corduroy road," remembered Wilbur Hinman of the 65th Ohio. "We learned that the 19th Kentucky, the fourth regiment of our brigade, was a few miles ahead working out its road tax. All of the available officers and men of the three regiments were turned out for duty. The mire in the road was of almost fathomless depth. Our unsoldierly job promised to be both tedious and disagreeable, and the promise was abundantly realized. The process was to fell trees, cut the trunks into lengths of 16 feet, split these into sections and lay them traversely, covering them with a few inches of earth."

In a heavy downpour, the men dove into the project with a gusto, their inexperience with the work evident in the comment of David Crosson of the 64th Ohio that the task "will be a small job." It was anything but: progress started off slowly but with each passing day, the number of sick men left behind in camp slowed the work to a crawl. William Hartpence of the 51st Indiana remembered that "we cut down huge chestnut trees that were abundant there, quartered them, and laid them in 16-foot lengths across the road." Another recalled that "it was a perfect wilderness of underbrush. Whether the puncheons we put in the road will improve it very much I know not, but it will be rough enough to answer all ordinary purposes as well as tend to increase the swearing of the drivers of the supply trains that pass over it."

"In four days we made only a mile and quarter of road at which rate it would have taken four or five months to reach Somerset," Wilbur Hinman wryly commented. "The exposure began to tell on the men. Hospitals were established in Stanford and every day dozens were sent there. No one felt well and everybody had the blues. The force of effective men that went out day after day to flounder in the mire grew constantly smaller and the work advanced more slowly. There was no straw for the tents and the men slept with little to protect them from the dampness of the soaked ground. Our life, day and night, was utterly and irretrievably miserable."

To help pass their evenings in the wet, muddy camp at Hall's Gap, the men of the 51st Indiana made pipes and trinkets from the abundant laurel root. Most of the time, the men arrived back from the road too tired to do much more than grab a bite of hardtack to eat, a few sticks of wood for the stoves in their Sibley tents, and achingly climb into their blankets prepared to spend the night spooning with their comrades to keep warm. "many of the boys had measles, and many were troubled with diarrhea," Hartpence wrote. The men were issued flour, but most had no idea what to do with it, but soon learned the ancient art of making "doughnuts" over a fire.

One event that did spice up life on the road was the passage of the body of General Felix Zollicoffer on January 31, 1862. "We had already seen live generals but no dead ones of either side," Wilbur Hinman remembered. "There was a great rush to get sight of the coffin containing all the remained of Zollicoffer; a few succeeded in gratifying their curiosity but more did not. During the entire remainder of the war, the death of this soldier was the subject of a harmless jest. Whenever anybody inquired what was the news, he was gravely told, "Zollicoffer's dead." In the army the air was generally full of the wildest and most absurd rumors concerning the military operations in our own and other departments. We learned that not a tithe of what we heard could be believed. But we knew that General Zollicoffer had been gathered to his fathers; we had seen the hearse that was bearing his body to the grave and some had seen the coffin itself."

Following Zollicoffer's passage, General Wood decided it was time to see if the road his men had been laboriously working on for nearly a week was ready for usage. "The train wound gayly up the hill; the driver of the first wagon had a knot of red, white, and blue ribbons fastened to the butt of his whip and was singing in a high key as he let go his long lash with unerring aim and tickled the ears of his mules. Pretty soon the forward wheels of the wagon struck the corduroy, displacing several of the slabs, and when the hind wheels attempted to follow they nearly sank to the hubs. The driver ceased singing and began to swear, hardly stopping to take a breath for two days and night, for those mule drivers who had to pass over, or under, or through our corduroy road at Hall's Gap continued their profanity right along after they went to sleep."

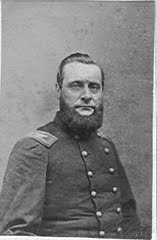

|

| Colonel Abel Streight, 51st Indiana |

Colonel Abel Streight of the 51st Indiana dove right into the fray, "his soldierly pride touched at the apparent failure of our road," grabbed a long timber, and started to pry up the wagon wheels. "Others lifted at the wheels, the driver cracked his whip and launched at the mules some of those blood-curdling oaths that all army teamsters held in reserve for such extraordinary emergencies. This combined vocal and physical demonstration was successful and the wagon went on with bumps and thumps and jumps and slumps for a few rods when another yawning chasm opened in the road and the wheels went down again. Each successive wagon left the road in worse condition than those that had gone before. Here and there the rails and logs were jammed in a heap, some turned at all angles, and others sailing around in the mud. As the train toiled on with sometimes a dozen wagons stuck, the whole working party was called in and the able-bodied men of the whole brigade betook themselves to the task of prying out the wagons and helping on their way," remembered Hinman.

|

| Brigadier General Thomas J. Wood |

Observing nearby with a growing sense of disgust and anger was General Thomas J. Wood. It was plain as day that the road was a disaster. "General Wood rode along the scene of action, the mud and water squirting out from under the hooves of his horse. His mind seemed to be in high ferment for he shouted with extraordinary vehemence as he endeavored to direct the labors of his soldiers," Hinman wrote. Wood's horse stumbled over some of the logs and nearly unhorsed the General, who as soon as he recovered "gave the men around him a red-hot lecture for building such a road. His words almost singed their hair. In fact, during those days General Wood delivered a regular course of lectures full of fire and brimstone."

By sunset, the leading wagon had made it all of a one mile down the corduroy road, upon which no construction progress had been made as the work gangs had been pulled to help pry out the bogged down wagons. The 1st of February was a repeat of the 31st of January: bogged down wagons, mud flying in all directions, braying mules, swearing teamsters, General Wood's bellowing, a lot of mud, sweat, and tears. "I feel moved to say that the picture I have given is not in the slightest degree overdrawn," Hinman stated. "I call to the witness stand any or all who spent those two wretched weeks at Hall's Gap, even the memory of which is a nightmare. No language can go beyond the reality of our actual experience."

General Wood was anything if tenacious; the soldiers hacked and pried and swore and strained to move the wagons along for another week, managing to get the road all of six miles from their camp at Hall's Gap, with 29 more miles to go to Somerset. The affair was as fruitless as the Army of the Potomac's Mud March albeit on a smaller scale.

But the fortunes of war soon provided a reprieve to the mud-caked Federals of Wood's brigade. On February 6, 1862, General U.S. Grant's expedition against Fort Henry had successfully taken that Confederate bastion, and the Federal armies of Grant and Buell started to make a full-court press to drive into middle Tennessee. "On the morning of February 8th, we turned out as usual and shouldering axes and shovels started for the scene of our daily toil," recalled Hinman. "We had not gone more than a mile when a messenger came riding out with orders for us to break camp and march immediately. When the nature of the order was made known the woods rang again and again with cheers. Our destination, whatever it might be, was a matter of perfect indifference to us. We just wanted to march- march anywhere. The work of preparation was rushed with extraordinary activity. In an hour, nothing but the debris of camp remained. There was a quick response to the drum as we formed for the last time along that awful road. We were rejoiced to learn that we were not to flounder through the mud toward Somerset. We turned our toes the other way and started down the hill with nimble feet and singing "Out of the Wilderness" with tremendous effect.

Tell me how did you feel, when you come out of the wilderness?

How did you feel, when you come out of the wilderness?

How did you feel, when you come out of the wilderness?

Lean and lonely lord

Well, I felt like shouting, when I came out of the wilderness.

I felt like shouting, when I came out of the wilderness.

I felt like clapping, when I came out of the wilderness.

Leaning on the Lord

Well, I told everybody, when I come out the wilderness.

I told everybody, when I come out the wilderness.

I told everybody, when I come out the wilderness.

Lean and lonely Lord

Tell me how did you feel, when you come out the wilderness?

How did you feel, when you come out the wilderness?

How did you feel, when you come out the wilderness?

Lean and lonely Lord

Well, I felt like shouting, when I come out the wilderness.

I felt like shouting, when I come out the wilderness.

I felt like shouting, when I come out the wilderness.

Lean and lonely Lord

Well, I told everybody, when I come out the wilderness.

I told everybody, when I come out the wilderness.

I told everybody, when I come out the wilderness.

Lean and lonely Lord

Comments

Post a Comment