Squirrel Hunting the Rebels at Glorieta Pass

Private Charles H. Farrar served in Co. G of the 1st

Colorado Infantry under Captain William F. Wilder, a unit that had a unique and

interesting history. The regiment entered service in the fall of 1861 but was

not accepted for service by the Federal government. Regardless, the regiment

was organized under territorial authority and set out to battle the Confederacy

among the plains, deserts, and mountains of the far West.

A Confederate army of Texan and New Mexican volunteers under General Henry H. Sibley marched north from Texas in early 1862 aiming to secure control of the southwestern territories for the Confederacy and were confronted by a small Union army led by Colonel Edward R.S. Canby. Canby's force, a mixed bag of New Mexico volunteers, U.S. Regulars, and two regiments of Colorado infantry, among them the 1st Colorado controlled northern New Mexico. The true prize for the Confederacy was control of the Colorado, Nevada, and California gold and silver mining districts; Canby’s mission was to simply maintain Union control of the area.

After much maneuvering, the two forces clashed at the

Battle of Glorieta Pass, New Mexico on March 28, 1862, a battle known as the “Gettysburg

of the West.” The two armies of roughly 1,000 men each pitched into one another

in a long swirling fight through the canyon, and at the end the Confederate

forces held the field. But during the battle a Union detachment torched the

Rebel supply train, without which further military action was impossible; this

forced the Confederates to retreat back to Santa Fe the next day and plunked

the mantle of victory into the Union’s lap.

Private Farrar’s account picks up the

story in late February 1862 and explains the events of the campaign as he

experienced it within the ranks of the 1st Colorado. The native born Vermonter served with the 1st Colorado into 1863, then returned home to Iowa where he served as a sergeant in the 9th Iowa Cavalry. Farrar died November 10, 1915 and is buried at Forestvale Cemetery in Helena, Montana. His letter was

published in the May 3, 1862 issue of the Burlington

Hawk-Eye in Burlington, Iowa.

|

| Battle of Glorieta Pass, New Mexico, March 28, 1862 Roy Anderson |

Fort Union, New Mexico

April 4, 1862

We left

Camp Well on February 22, 1862 en route to Santa Fe, New Mexico Territory. We

had a fine time, good weather, and good health throughout the regiment.

Everything went smoothly until we got within 150 miles of Fort Union when we

heard that Colonel Canby had had a battle with the Rebels and was defeated, and

that the Rebels were marching on Fort Union. [The Battle of Valverde was fought

on February 20, 1862] We marched 30 miles that day, stopped on the Red River

and got some supper, unloaded our wagons, and leaving behind a guard of 100 men

to take care of the baggage and beef cattle, we jumped into the wagons and away

we went as fast as mule flesh could carry us. We traveled until 2 o’clock in

the morning when we stopped, made some coffee and took a bite, and away we

went, traveling all day before we came to a Mexican town where we stopped and

stayed all night. We started out in the morning before daylight and heard that

the Rebels were within 45 miles of Fort Union; we lost no time and at sundown

were landed in the fort.

We soon

learned that we were not in any danger- the men in the fort had gotten scared

and got up this report. We remained in Fort Union until the boys we left back

came up. We drew a suit of clothing and exchanged our old guns for new ones. We

were beginning to get tired of staying at Fort Union when there was an order

read on dress parade at night that we should be ready to march in the morning

with a pair of blankets to the men and just the clothing we had on our backs.

So, we

started with about 60 wagons of grub and ammunition and four pieces of heavy

artillery and four pieces of light artillery. We traveled three days and camp,

hearing news that the enemy was advancing upon us. Major [John M.] Chivington,

at the head of about 300 men, started to meet them (by the way, they were 40

miles ahead of Chivington) The enemy had taken their position in a canyon

[Apache Canyon], one of the best positions in the world for a defense. The Major

marched into the canyon, found the enemy ready for him, who fired their cannon

and musketry but did little damage, the shots going over their heads. So, the

Major ordered his boys to make a bold charge; no sooner said than done. The

Rebels saw the boys coming with blood in their eyes, took to their heels and

away they went, leaving their dead and wounded on the field. It is not known

how many they lost but it is supposed about 70. Our loss was four men.

The

Major gathered up all the guns they left behind and broke them over the rocks.

The Rebels sent in a flag of truce. The Major sent a dispatch to us and

retreated about eight miles and took his stand. You can bet we were not long in

getting ready. We marched all night and came to the Major’s camp before sun-up,

ate some breakfast, got ready, and started to meet the devils. They had

advanced on us and taken their position at a place called Pigeon’s Ranch right

in a canyon covered with trees and bushes [Glorieta Pass]. It so happened that

my company was detailed to support one of the batteries and we had to march in

rear of the battalion. We had not gone far before we could hear the booming of

the cannon and well knew that the fun had commenced.

My

Captain, William F. Wilder, came riding up and we took a double quick and soon

came to the scene of the action; one of our batteries had taken its stand. As

we came up to our battery, the bullets from the enemy whistled all around us

and one of our boys fell, shot through both legs. We took our stand behind our

artillery which we were ordered to support. We laid down on our bellies and the

Rebels would shoot over us every time. We could not see the enemy, the bushes

were so thick, and the devils undertook to flank around us and come in and get

our guns, so our Captain was ordered to take the first platoon of his men and

go upon the hill and cut them off. I went with him. We took our stand upon a

ledge of rocks where we had a good chance to give them the contents of our

guns. We were within 200 feet of them and when they would stick their heads

over the rock, we would give them hell. We lost one man at the rocks, but he

was not killed instantly and two more wounded, and on the side of the rocks where

the Rebels were there were 50 killed and wounded. It put me in the mind of

squirrel hunting.

While

we were peppering it to them at the rocks, the other boys were giving it to

them down in the canyon. The devils made a charge on our battery, but our boys

who had remained back with the battery made a rush at them and they ran. There

was a continued roar of cannon intermingled with musketry when they made the

rush at our battery; our gunners discharged their four guns amongst them and it

mowed them down right and left. After fighting six hours, we discovered about

300 Texans coming over the rocks where we were and the captain thought it was

useless for so few of us to fight hand to hand, so he ordered us to retreat and

as we did so, they poured a volley of musketry into us which wounded one of our

boys, but they did not get him; I was by his side and helped him along.

|

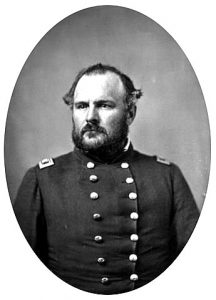

| Major John S. Chivington 1st Colorado Infantry |

When we

got down where our battery was, we found our men on the retreat. They retreated

a little ways, made a stand, and waited for them to come up, but they retreated

the other way. So, we went into camp and the Rebels sent a flag of truce; they

wanted a truce for three days, but our Colonel would not grant it longer than

the next forenoon. The best of the joke was that while we were fighting, Major Chivington

took between 300-400 men, went over the mountains, came to where they had left

their train of 64 wagons of provisions, ammunition, clothing, etc., set fire to

them, and burnt them to ashes, killed a lot of mules, and destroyed two pieces

of artillery. The Rebels who were guarding the train fired on the Major with

both guns but did no harm, and having accomplished his object, he returned to

our camp.

The loss of the enemy, according to their own account, was 400 but we think it was much larger. [Official losses were 222 Confederates killed, wounded, and captured, 147 Union for the entire engagement.] We expected they would attack us again the next day, but as soon as they got their dead buried, they left for Santa Fe.

For a lengthier discussion on the 1st Colorado at the Battle of Glorieta Pass, check out this superb article from the Iron Brigader.

Comments

Post a Comment