Honor Fearfully Won: A Stones River story of the 39th Indiana

In

the pre-dawn hours of Wednesday, December 31, 1862 outside of Murfreesboro,

Tennessee, Private John Wilson of Co. D, 39th Indiana Infantry

stamped his feet and rubbed his hands together to fight off the damp chill. The

company had been sent out on picket after sunset the night before eating a supper

of raw bacon and hardtack; they were not permitted fires. All night long, he

and his comrades serving on the picket line of General August Willich’s

brigade, constituting the extreme right wing of the Army of the Cumberland, had

heard the noises of a Confederate Army on the move in their front. A jumpy

Federal picket had shot a cow during the night which had blundered into the

lines. A long line of campfires stretching to the west appeared to indicate

trouble in the morning. It was a harrowing time for the Shiloh veterans.

Corporal

Henry N. Rankin could hear “the Rebel pickets conversing in a low tone. I was very

anxious, as an officer having charge of the picket line. I cautioned our

reserve officers as to conditions in our front but they thought it would come

out all right. I warned all of the pickets of a very early attack and told them

at the first gun to give way and make for our reserve. I had placed the last

pickets on duty before daybreak and had scarcely reached my reserve and packed

up my knapsack when the first gun was fired on my pickets. They could scarcely be

seen and looked more like trees than pickets. I was prepared to run. I called

to all I could reach and told them where to go,” Rankin recalled. “A comrade

and I made for a fence a short distance away wither several others. Several who

jumped the fence were shot as they jumped over and I had just alighted on the

ground when a ball struck my head, knocking me to the ground. All of the

pickets that were not shot down at the first volley were now scattered badly.”[1]

Private

Noah W. Downs of Co. D likewise was run off the field before dawn. “Firing

commenced in front of Kirk’s Brigade,” he wrote. “They gradually gave way

leaving our left entirely exposed. As soon as he was apprised of the fact,

Colonel [Fielder A.] Jones ordered Co. D to fall back and join on the brigade

again but no sooner done than the Rebels came over the hill charged bayonets

and yelling like Indians. The balls were flying thick and fast, our support on

the left had retreated and we were left all alone.” Dozens of the 39th

Indiana were gunned down at the outset, and most of Companies B and C were

captured outright by the rapidly advancing Confederate battle line.

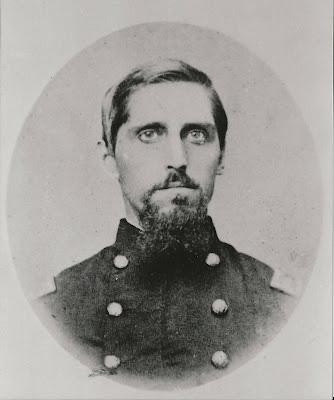

|

| Private Aurelius M. Willoughby, Co. H |

As

the regiment fell back in confusion, scattered pockets of Federal resistance vainly

tried to stem the Confederate onslaught. Private Aurelius Willoughby of Co. H recalled

seeing “a very large burly-looking soldier belonging to the 89th

Illinois; he was behind a large tree loading and firing very coolly. Every time

he would fire he would yell out to the advancing Rebs, “Here’s your mule!” and

then load again. After firing several shots and yelling as usual after each

shot, he caught an ounce ball in his shoulder as he stepped from behind the

tree to fire. Yelling out that he was shot, he about faced, threw his gun away,

and did some of the tallest running to the rear that was done, never stopping

to look back for fear he would catch another one. The mule business was ‘played

out’ with him,” Willoughby wrote.

As

two Confederate infantry brigades under Generals Matthew D. Ector and James

Rains pushed Willich’s and Kirk’s men out of their position at the wooded intersection of Gresham Lane and the Franklin Pike, a brigade of Confederate

cavalry under John Wharton swooped out around the left of the advancing

Confederate battle line and galloped into the Federal rear, cutting off

prisoners from the broken Federal brigades by the bushel. Wharton’s 8th

Texas Cavalry (Texas Rangers) captured most of the 39th Indiana,

even capturing the regimental colors for a time.

Federal

resistance continued even after the men were captured, as remembered by Noah

Downs. “Captain [Thomas] Herring with several of his men were captured and the

guard having charge of him ordered him to double quick, but the captain told

him in his peculiar way that he had “quit doing that.” The guard, much enraged,

drew a revolver and swore he would shoot him. “Shoot and be damned,” yelled the

captain, “I’m tired.” About this time, our cavalry made a dash on the Rebs and

then Herring turned on the guard and told him, “Now sir, this changes the

program. You dismount, take off that saber,” he said. The fellow wilted, got

off and held the horse while the captain mounted,” Downs related.[2] “They captured the balance

of our boys and also the colors,” remembered Private Aurelius M. Willoughby of

Co. H. “But the 4th U.S. Cavalry and the 4th Ohio Cavalry

dashed in and ran the Rebels off, releasing us and recovering our colors which

we have now.”

But

for hundreds of Federals, the battle was over, among them Private John Wilson of Co. D who tells this story of his time in Rebel hands:

“I

was taken by the Texas Rangers and they were all about half drunk or a little

more. After robbing me of everything they wanted, I along with a great many

others was turned over to some Tennessee infantry to be taken into town and a

half dozen Rangers also went with us; indeed, the Rebel soldiers were very

anxious to guard prisoners and the corporal in charge had to send several back

to their regiments. The Rebels were very kind and used us as best they could. I

saw several of them dismount and help up wounded Union prisoners on their

horses and walk themselves. They entered into conversation with us very freely.

One told me a colonel had been around their lines four or five times with whiskey

that morning before daylight and everyone had as much to drunk as he wanted. He

also told me they had been in line of battle all night and that the campfires

we saw were all false, as they lay close to our lines and could hear our

pickets talk and even sometimes make out what they said.”

|

| The Confederate guards earned praise from their Yankee prisoners for their fair treatment. |

“Every

one of them had plenty of tobacco, an article we all were sadly in want of.

They gave us the weed very readily and liberally; not only so on the battlefield,

but all over the Southern states. The Rebel soldiers treated us far better than

the citizens all throughout our trip through the South, but there were some exceptions.

When we got to Murfreesboro in going up the street to the courthouse, I saw

four or five women standing on a portico. When we got opposite to them, an old

Jezebel of iniquity who had no teeth mumbled out in the peculiar manner of

toothless people, ‘I would sooner have see them all left on the battlefield,”

then the rest of them joined in the same cry. One of the Rebel soldiers riding

alongside of me said, “You would not say that you damned old bitch if you had

to go and fight,” but not loud enough, of course, for her to hear.”

“When we got to Tullahoma, a large crowd assembled to see us and many of them provided corncakes which they distributed among us. I got a piece from a soldier that had just got home from the North, having been a prisoner, he procured all he could for us, stating that he had been well-used when a prisoner with the Federals. In marching through the streets of Chattanooga, several of the citizens indulged their spite by calling us nicknames, laughing, and insulting us. Their officers and soldiers felt ashamed of them and said “twas like fighting a Negro who durst not fight you.” We stopped three hours at a place called Ringgold, Georgia and the people here were very social and some conscripts we talked to wished very much to be in our situation, prisoners of war. All along through Georgia, Alabama, and eastern Tennessee, they people are heartily tired of the war.” Wilson’s contingent of prisoners were sent south from Chattanooga to Atlanta and had made it into southern Alabama when the train received orders to bring the Federals back north and to send them through eastern Tennessee for exchange at Richmond, Virginia.[3]

The

warm welcome the Federal prisoners received throughout the South didn’t sit

well with some, particularly the editor of the Athens Post. “Several

thousand Federal prisoners have passed this place recently going in the

direction of Richmond. The prisoners were mostly western-born, with a heavy

sprinkle of the foreign element. On Sunday, a train loaded with that sort of

livestock was detained at the depot an hour or two and the rush to see the

captured elephant was great. It is said the sight of the prisoners made some of

the Secesh, who have stuck pretty close to home since the war commenced, as mad

as Dutchy’s cow and that they cussed the dreadful Yankees and wanted to fight.

The Lincolnites or Union men as they prefer to be called, were out in force and

it is reported that the billing and cooing between them and such of the

prisoners as we condescend to notice them was marked enough to be disgusting. It

is stated that several females had the bad taste to wave with their

handkerchiefs an affectionate adieu to the departing prisoners as the train

moved off. The last report would seem almost incredible and we hope there is no

foundation for it,” it opined.[4]

This

phenomenon of Unionist support in the deep South was also something Private

Wilson commented upon. “At Greenville, Alabama, they talked nothing but the

most rabid secession. One would think they were the bitterest enemies we had.

There was quite a gathering of young women on the platform, one of whom waved a

Secesh flag when we started from the depot. Next day, when we returned, I saw

the young lady at the depot again. I asked her to let me see the flag she was

waving yesterday. She said it was at home but if I would take it North and show

it to the young ladies there, she would give it to me and ordered a young Negro

to go for it. I told her I expected to capture one on the battlefield to show

both old and young ladies at the North. ‘Well,” says he, ‘I suppose I may speak

my real sentiments to you. I am for the old Union and so are many here. I only

waved the flag yesterday because my family are suspicioned of being traitors to

the Southern Confederacy.’ A Secesh captain coming up in the platform at this

moment, she was afraid to be seen talking to a Union soldier,” Wilson remembered.[5]

[1] Corporal Henry N. Rankin, “Midwinter Battle of Stones

River,” National Tribune, July 22, 1926

[2] Private Noah W. Downs, Howard Tribune (Indiana),

February 12, 1863, pg. 1

[3] Private John Wilson, Howard Tribune (Indiana),

February 5, 1863, pg. 1

[4] “Federal Prisoners,” Athens Post (Tennessee),

January 16, 1863, pg. 2

[5] Wilson, op. cit.

Comments

Post a Comment