Undone by the Mud: Vignettes of the Mud March

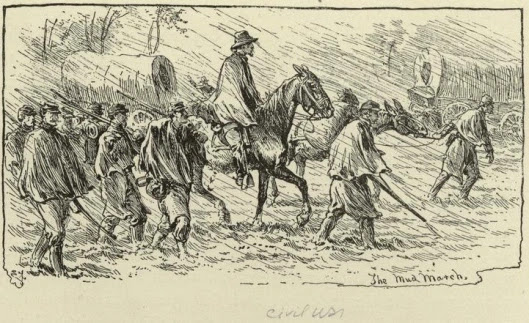

In mid-January 1863, General Ambrose Burnside directed what proved to be his final offensive move as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside’s aim was to steal a march on his opponent General Robert E. Lee, seize Banks’ Ford on the Rappahannock, and push into the rear of Fredericksburg. It was a bold move, but within two days of beginning, the drive was hopelessly mired down in the mud and the dejected Federals tramped back to their camps near Falmouth.

The offensive

became known as the Mud March, and it marked both the end of Burnside’s tenure

as commander of the Army of the Potomac and the nadir of the war for his army. Today’s

post will revisit the Mud March through the words of the men who were in the

thick of it, slogging through the Virginia mud in a downpour. It is the picture

of misery as our eyewitnesses will attest.

All of the

accounts comprising this post originated from Griff's incomparable

Spared & Shared website.

The march begins

The weather and roads had been in excellent condition since the late battle at Fredericksburg, and on the 19th of January, 1863 the columns were put in motion with such secrecy as could be observed. The Grand Divisions of Franklin and Hooker ascended the Rappahannock by parallel roads and at night encamped in the woods at a convenient distance from the fords. ~ William Swinton

We are now under marching orders and I think it must be over the river but I dread the consequence as the army is disheartened. Burnside is bound to cross the river at this place and to retrieve his loss but all the generals are opposed to it so you can judge of our prospects. It is heart sickening; I can assure you. But I shall do my duty regardless of others, or at least I think I will now, but no one can tell till after the fight is over. I feel for others as well as myself. I know if a fight comes off now, that the wounded must suffer greatly, but then I will not borrow trouble as it comes soon enough. ~ Colonel Clark Swett Edwards, 5th Maine Volunteer Infantry, 6th Army Corps, Franklin’s Grand Division

The 11th Army Corps is under orders to move any time at an hour’s notice so you see we may march again in a month just as the Rebs happen to work, I suppose. I don’t believe that they know all that is fixing for them but they will find out perhaps. The roads are awful muddy. It takes 20 horses to haul one siege gun and if it keeps on raining, I don’t believe they will be able to move at all. Don’t care of we do stop here about a week and get acquainted. We have got good quarters [and] are near the landing where we can get plenty of food. ~ Private Sylvester Rounds, Co. D, 17th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry, 11th Army Corps, Reserve Grand Division

As I said before, we left about noon with our knapsacks, three days rations & forty rounds of cartridges, and started off. We marched on until about dark when the Colonel ordered us to halt, & he then read an order from Burnside saying that we was about to meet the enemy again, and hoped we should “strike a fatal blow at the Rebellion.” After that was read, we marched on until about 9 o’clock, when we halted for the night in a very severe rain storm, and went to work putting up our shelter tents and turned in for the night on the cold wet ground. I soon went to sleep, for I was very tired, but we hadn’t been to sleep long, before I found that I was lying in the water—which wasn’t very pleasant—but I had to make the best of it until morning. ~Private Edgar E. Griggs, Co. E, 29th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry, 11th Army Corps, Reserve Grand Division

The storm breaks

During the night, a terrible storm came on and then each man felt the move was ended. It was a wild Walpurgis night, such as Goethe paints in the Faust. Yet there was brave work done during its hours, for the guns were hauled painfully up the heights and placed in the positions while the pontoons were drawn down nearer to the river. But it was already seen to be a hopeless task. ~ William Swinton

We started from camp day before

yesterday at about 4 o’clock p.m. and have only been able to proceed about six

miles. The first day we marched about three miles, when we flanked off into the

woods and bivouacked for the night. We had no more than got our shelter tents

up before it began to rain and continued all night and in the morning at 7

o’clock when the general sounded, it was still raining and the mud was a foot

deep, making it almost impossible for the artillery to move.

Going up some of the hills, they had to put twelve horses onto the cannon to draw them up. We was only able to march about three miles this day when we again flanked down into the woods where we now lay, unable to proceed any further until it clears off and the roads get into condition. Jack, this is going to be a tough campaign and will kill more men than the Rebel bullets. ~ Second Lieutenant Anthony G. Graves, Co. G, 44th New York Volunteer Infantry, 5th Army Corps, Hooker’s Grand Division

Soon after we got our tent

pitched and our coffee made, it began to rain and continued all night. So far

as I have seen, there is but very little gravelly or stony land in this state,

so the roads cut up quite easily when wet. As a consequence, on Wednesday

morning, the mud was getting bad. The artillery horses having stood out in the

rain without any protection were pretty well chilled. This together with the

heavy roads made it very difficult getting the trains in motion.

We breakfasted at daylight,

packed up our things — wet tents and all — and “fell in.” It was 10 o’clock

before we got off and then our course was very slow. At 1 p.m., having marched

about four miles, we turned off into a fine oak wood and were ordered to

bivouac. Soon our tents were up and our fires burning. The drizzling rain still

continued, but being favorably situated, we got things in comfortable shape for

the night.

Yesterday we remained quiet and made ourselves as contented as possible. Today we have been out building corduroy roads through the mud holes in order that the artillery and wagons may get back to their camps. ~ Second Albert Nathaniel Husted, Co. E, 44th New York Volunteer Infantry, 5th Army Corps, Hooker’s Grand Division

On the 20th we left camp about noon & marched about 8 miles farther up the river and camped for the night. That night at about bedtime, it commenced to rain & the wind to blow very cold.

21st—Woke up—or rather was awake most all night—had wet blankets but on the whole was in very good shape. We broke camp this morning and marched on two or three miles, it is raining all the time. At first, we were ordered out to build fires but soon it was countermanded and were ordered to pitch tents and night found us with our tents up, good fires, wet blankets, overcoats, and wet, cold ground to sleep on. In fact, there was but a small part of us but what was wet all over.

22nd—It rained all night & the wind blew cold. Our things were about ringing wet. It has rained most all day today but it would not be so bad if the wind did not blow so cold. We struck tents this morning but were ordered to put them up again. We look like a lot of drowned rats. Some of the boys swear some at one thing and some at another. Some joke and laugh. The latter, I think, is for the best. ~ Sergeant Charles E. Bradley, Co. I, 32nd New York Volunteer Infantry, 6th Army Corps, Franklin’s Grand Division

Bogged down in the mud

The clayey roads and fields under the influence of the rain became bad beyond all former experience. By daylight, when the boats should all have been on the banks ready to slide down into the water, but 15 had gone up, not enough for one bridge. ~ William Swinton

We was to try a flank movement but Burnsides got stuck in the mud. Our brigade and others left our guns and went to work and cut trees and logged the road all the way so as to get our artillery back for they was stuck. They had to have 12 horses on a piece. We carried all the fences that the farmers had to make roads of. You would laugh to see them march a brigade up to a fence, then charge on every man with a rail on his back. I tell you, they take down the fences. It ain’t no use to tell about moving for they can’t. ~ Private Andrew J. Lane, Co. D, 32nd Massachusetts, 5th Army Corps, Hooker’s Grand Division

We left camp on the 20th inst. with the intention to cross the [Rappahannock] river above Falmouth and flank the Rebel works and make them retreat to save their communication. Their works would not be of any account then for they all point on Fredericksburg. We attack them left flank, the works are not worth anything. But God seems to be on their side for it was [a] clear, nice morning when we started and before night the rain poured down in torrents and made the roads impassable for artillery or wagons so we could not move any farther. It rained the next two days most as hard as the first night. Mud was knee deep in the road on the level and in the ravines, the mules and horses would go in all over. I saw 6 mules fast in the mud hitched to a wagon and all dead. In another place I could just see the backs of the mules. They had the cavalry carrying grain and hard bread on their horses.~ Corporal Mair Pointon, Co. A, 6th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry, 1st Army Corps, Hooker’s Grand Division

We expected to go across the

river that day, but it was so muddy that we couldn’t hardly walk, but we

marched on towards Warrenton until about 1 o’clock, when we couldn’t get any

farther, and the Gen. marched us into a thick pine woods and then put up our

tents, and built up our fires, and dried our blankets for our bed. We cut some

pine brush and laid on the ground. We went to bed about 6 o’clock and slept

very good through the night. It rained very hard through the night, but we

didn’t get much wet. That day we hadn’t much to eat, for the wagons couldn’t

get to us with provisions. It didn’t rain much that day, so at night we had a

very good night to rest.

The next day (Friday), we received orders to go back to our old camp, for we couldn’t go any farther on account of the mud. So about 8 o’clock we packed up and started back for our old camp. The whole Army was on the move and it was a great sight. We marched until about noon, and then halted for to get something to eat, but we didn’t have much for we was eat out. In the afternoon, the clouds cleared away and it was quite pleasant, but there wasn’t much of the regiment together for they were scattered along the road for three miles. ~Private Edgar E. Griggs, Co. E, 29th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry, 11th Army Corps, Reserve Grand Division

We marched away up the river intending to cross and attack the Rebels. Well, we got up where we intended to cross the river from the next morning when Lo! what a relief to us, we found that it had rained there all night and that the splendid roads were almost converted into impassable mud. All of a sudden the pontoons and artillery were all stuck fast. How we had to go on and pull them out going up to the knees in the mud and water. We soon perceived that this advance movement was checked for the present by the sudden change of the weather. There we were in mud and the boys believe that the Lord sent the rain on purpose to prevent our crossing over the river. ~ Private Thomas H. Capern, Co. E, 4th New Jersey Volunteer Infantry, 6th Army Corps, Franklin’s Grand Division

The day after I sent my last letter we were set at work drawing out Pontoon boats with a drag rope. It took about 100 men to a boat. It was so bad that the horses could not draw them out so they hitched up us soldiers and we had to draw them about two miles. The mud was very deep. We got through about 3 o’clock & started for home but did not go but a few miles and stopped for the night. It rained that night and we had orders to be ready to march at half past seven but did not go until about noon and then started for camp which we reached about dark. ~ Sergeant Charles E. Bradley, Co. I, 32nd New York Volunteer Infantry, 6th Army Corps, Franklin’s Grand Division

|

| Banks' Ford on the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, Virginia |

Undone at Banks’ Ford

The night operations had not escaped the notice of the wary enemy and by morning Lee had massed his army to meet the menaced crossing. In this state of facts, when all the conditions on which it was expected to make a successful passage had been balked, it would have been judicious in General Burnside to have promptly abandoned an operations that was now hopeless. But it was a characteristic of that general's mind never to turn back when he had once put his hand to the plough. ~ William Swinton

We were told that the move was

secret—not known by the enemy—but as soon as we got to the river, and when our

pontoons were still in the rear, the Rebels cried across the river to us and

asked us if we wanted any help in getting our pontoons in position. If so, they

would come over and help us. So much for our secret move, known to the enemy

before to ourselves, and so it always has and always will be. We can make no

move while in an enemy’s country without the enemy getting wind of it about as

soon as it is known to ourselves.

I must say I was glad that the rain prevented our crossing the river for the prospect ahead was anything but encouraging for our Division (Birney’s) was to take the lead to cross in open boats before the bridge was put down and our regiment the first to land on the other side of the river. As soon as on the opposite bank, we were to deploy as skirmishers to be supported by the 28th and 40th New York and I guess that by the time we had advanced many rods, the 3rd Maine would of been most beautifully less for we only numbered about 180 men and these soon would of bit the dust for the Rebels were prepared for us. ~ Sergeant Hannibal Augustus Johnson, Co. B, 3rd Maine Volunteer Infantry, 3rd Army Corps, Hooker’s Grand Division

Dejection and Defeat

General Burnside fancied that he discovered another and deeper cause [for the failure], that aside from the interference of the weather, would have balked his projected campaign. This cause was a lack of confidence in him which he believed to be entertained by the leading officers of the army. Among these were officers were Generals William B. Franklin and Joseph Hooker, respectively commanders of Grand Divisions, and his first act on the return of the expedition was to prepare an order dismissing from the service Generals Hooker, Brooks, Cochrane and Newton, and relieving from their commands Generals Franklin, William F. Smith, Sturgis, Ferrero, and Colonel Taylor. Burnside took this order to Lincoln and demanded its approval or acceptance of his resignation. Lincoln chose the latter course and promptly put Joe Hooker in command of the army. ~ William Swinton

Wasn’t this last move we made a

big thing? How much did the move advance our cause—not much I think, and if

curses would put a man underground, Burnside and the War Department would of

been by this time in the neighborhood of China for to move at such a time as we

did was the height of folly and the simplest private in the ranks knew as much

and that nothing but disaster would attend the move.

When we were ordered to move, I

like many other very foolish persons burnt up our chimneys thinking if we

crossed the river, we should be either killed or taken prisoner and so of

course should not want our chimneys anymore. And if we were driven back, we did

not expect to stop until we reached Washington. So, we placed the incendiary

torch to our supposedly worthless houses and soon had the satisfaction of

seeing them a heap of smoldering ruins.

But after our three days sticking in mud, we were ordered back to our old campgrounds. You can imagine how I felt when I saw the ashes of my house in place of the house itself. And I well knew that I had work before me for another house I must have. And to make matters worse, my chum—who always did his part of the work—was sick for the tramp through three day’s mud had fixed him up for a while and anyone but what was made of iron it would have served in a like manner. ~ Sergeant Hannibal Augustus Johnson, Co. B, 3rd Maine Volunteer Infantry, 3rd Army Corps, Hooker’s Grand Division

Sources:

Swinton, William. Campaigns of the Army of the Potomac. Secaucus: The Blue & Grey Press, 1988, pgs. 258-262

Civil War Letters of Hannibal Augustus Johnson, Co. B, 3rd Maine Volunteer Infantry, Spared & Shared: https://sparedshared22.wordpress.com/2020/07/22/civil-war-letters-of-hannibal-augustus-johnson/

Anthony Gardner Graves, Jr. Letters, 1862-1865, 44th

New York Volunteer Infantry, Spared & Shared

https://sparedshared22.wordpress.com/2021/07/09/1862-65-anthony-graves-letters/

Letter from Second Albert Nathaniel

Husted, Co. E, 44th New York Volunteer Infantry, Spared &

Shared

Civil War Letters of Andrew J. Lane, Co. D, 32nd

Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, Spared & Shared

https://sparedshared23.com/2023/04/01/civil-war-letters-of-andrew-j-lane-32nd-massachusetts/

Letters of Thomas H. Capern, Co. E, 4th New Jersey

Infantry, Spared & Shared,

https://sparedshared23.com/2024/01/12/letters-of-thomas-h-capern-co-e-4th-new-jersey-infantry/

Clark Swett Edwards to Maria Antoinette Edwards, 5th

Maine Volunteer Infantry, Spared & Shared

The Civil War Letters of Sgt. Charles E. Bradley, Co. I, 32nd

New York Volunteers, Spared & Shared

https://chasbradley.home.blog/

Edgar E. Griggs, Co. E, 29th New Jersey Volunteer

Infantry to Maria Louise Nock, Spared & Shared,

https://sparedandshared19.wordpress.com/2019/09/06/1863-edgar-e-griggs-to-maria-louise-nock/

Letters from Sylvester Rounds, Co. D, 17th

Connecticut Volunteer Infantry to Martha Rounds, Spared & Shared

https://sparedshared22.wordpress.com/2022/01/29/1862-64-sylvester-rounds-to-martha-rounds/

Letter of Mair Pointon, Co. A, 6th Wisconsin

Volunteer Infantry, to brother and sister, Spared & Shared,

https://sparedshared13.wordpress.com/2017/07/04/1863-mair-pointon-to-brother-sister/

Comments

Post a Comment