Yankee Preacher, Rebel Lawyer: The Intersecting Lives of Granville and George Moody

In a war defined by the theme of brother against brother, the amazing tale of Granville and George Moody and their journey through the Civil War highlights the interconnected nature of family and social life in the 19th century. It's a story that starts in Maine, weaves through the histories of both the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Cumberland, twists in and out of prisoner of war camps, and ultimately involves President Jefferson Davis in the final days of the Civil War and President Andrew Johnson in its immediate aftermath.

Granville

Moody was born January 2, 1812, in Portland, Maine to William and Harriet

Brooks Moody while his younger brother George Vernon Moody was born there in

February 1816. One technically could say that the brothers were born in Portland,

Massachusetts, as Maine did not become a state until 1820.

Regardless, the Moody family

moved to the state of Maryland in 1817 and there in 1830 the paths of the brothers parted.

Granville followed an older brother to Ohio to enter the mercantile trade and

eventually became a widely respected Methodist preacher. George attended Harvard

Law School, and upon graduation in 1842, set out with another brother to make

his fortune at the Mississippi River town of Port Gibson, Mississippi.

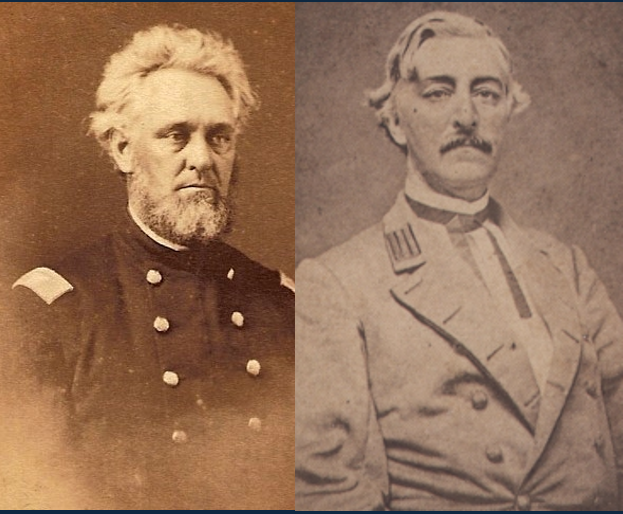

Both men exhibited strong

personalities. Granville made a name for himself within clerical circles for

his outspoken opposition to “Calvinism, Universalism, Socinianism, Radicalism,

intemperance, and disloyalty.” High-browed with deep set, fiery eyes, a

scraggly, silver beard, and wiry, unkempt hair to match, Granville possessed a

commanding appearance and pious manner that solidified his reputation as a

spiritual leader.

George Moody was no wallflower,

either. Setting up practice across the street from the Claiborne County

Courthouse shortly after his arrival, George gained the reputation as a fiery

and effective attorney, so much so that on several occasions he had to go into

hiding to foil assassination attempts. Like his older brother, George Moody possessed the same fiery eyes and white hair, but wore a mustache instead of a beard and effected a neater, more trim appearance as expected of an attorney. A Whig in politics, George fought

against secession when the crisis came after the 1860 election but to no avail.

When his state seceded in January 1861, he followed its fortunes out of the

Union.

The outbreak of the war found in

the brothers in opposing sections of the country and soon found them wearing

opposing uniforms. Granville was leading the Greene Street Methodist Episcopal

Church in Xenia, Ohio while George worked as an attorney in Port Gibson,

Mississippi. Despite lacking any military qualifications whatsoever, Granville

was commissioned as colonel of the 74th Ohio Volunteer Infantry in

late 1861 while in June 1861, George raised a company of hard-fighting Irishmen

from the stevedores and boatmen of Port Gibson and nearby Richmond, Louisiana. They started as infantry but by the time they arrived in Virginia, it was decided to form the company into what became known as the Madison Light Artillery.

Despite serving in opposing

armies, the two brothers never met one another in combat. Captain George Moody’s

battery was assigned to the Army of Northern Virginia where he earned a reputation

as a crack artillerist. Colonel E. Porter Alexander remembered George as “a

magnificent specimen of physical manhood, over six feet in height and weighing

about 200 pounds with a large, strong face, blue eyes, and no colored hair. He

always dressed well and I think rather prided himself in carriage and general

appearance not unlike General Robert E. Lee’s.”

|

| An 1847 advertisement for George Moody's law services in Port Gibson, Mississippi. |

The Madison Light Artillery

fought in the battles around Richmond and at Sharpsburg where Moody’s

leadership caught the attention of his commanders. General William N.

Pendleton, Lee’s chief of artillery, on April 10, 1863, complimented Moody on

his “intelligence, force of character, experience in governing men, and

well-proved resolution.” Major General Stephen D. Lee weighed in on April 19,

1863, from Vicksburg calling Moody a “gallant and competent light artillery

officer. He was under my command about one year in Virginia and behaved with

distinguished gallantry in the battles around Richmond and at Sharpsburg where

he led his battery with skill, doing great injury to the enemy.”

However, Colonel Alexander also

recalled that Captain Moody “was not an easy man to get along with and was

often in more or less hot water with his brother captains.” As a matter of

fact, Captain Moody got into a disagreement with fellow artillery commander Captain

Pichegru Woolfolk on the march to Gettysburg and on July 1, 1863, as Longstreet’s

Corps was approaching town, challenged Woolfolk to a duel which was to occur

the following day. The duel never came off: Captain Woolfolk was wounded the

next day and within a few months, Captain Moody and his battery would find

themselves sent to the western theater along with Longstreet’s corps.

It was there that George came

closest to meeting his brother in combat. The Madison Light Artillery arrived

on the Chickamauga battlefield in late September 1863, too late to take part in

the action. The 74th Ohio had fought at Chickamauga, but was long gone by the time Captain Moody arrived on the field with his battery. But he met someone who knew his brother Granville quite

well: Assistant Surgeon Abraham H. Landis of the 35th Ohio. As

Landis related in a letter sent home to Colonel Moody, “I saw your brother Captain

Moody who commanded a Louisiana Battery in the Rebel army. He asked a great

many questions about you and asked me to write to you when I got through the

lines and tell you for God’s sake to quit fighting and go to praying for

peace.”

|

| Assistant Surgeon Abraham H. Landis 35th O.V.I. |

As Surgeon Landis and Captain

Moody exchanged news, Landis no doubt filled him in on his older brother’s

active services with the Army of the Cumberland. The 74th Ohio

mustered into service in early 1862 and initially guarded Camp Chase in

Columbus, Ohio; Colonel Moody served as the camp commandant for several months

before the regiment transferred to Tennessee where it joined General Don Carlos

Buell’s Army of Ohio.

Whereas Captain George Moody

fought engagement after engagement with the Army of Northern Virginia, Colonel

Granville Moody was destined to fight just one battle with his regiment: Stones River. It was at Stones River that Granville Moody gained the

sobriquet the “Fighting Parson.” As he led his regiment into action on the

morning of December 31, 1862, he wheeled his regiment into line after a session

of prayer and exhorted them, “Now men, resume your praying, fight for your God,

your country, your kind, aim low and give them Hail Columbia!” His two center

companies opened fire and drowned out the end of his speech; his men later

claimed he said, “give them hell,” much to the pious colonel’s chagrin.

The 74th Ohio was

unable to hold its position in the cedars and commenced falling back. Colonel

Moody attempted to rally the men once within the cedars, sometimes at gunpoint

but with little success. “I rode on in search of further squads and as I neared

a wooded region, nine or ten graybacks sprang out of the woods and opened fire

on me. My horse was soon crippled, stopped short, and stood still. I applied

the spurs; he trembled and shrunk, and fell in agony on the ground, dead.”

Pulling himself from under the animal, Moody grabbed his two pistols and ran

towards the Nashville Pike. While hobbling along, a mounted officer tendered

his horse, but Moody’s lame leg failed him and he sent the man along. A few

minutes later, an Irish private from his regiment rode up to the colonel on a

captured Rebel horse. “Divil a bit; try again Colonel. Try again, man or the

devils will get ye, sure!” I tried again and the Patty almost lifted me into

the saddle, and amidst the zipping bullets, which came thick and fast, I strode

the saddle, and without waiting to find the stirrups, started for our lines.”

Colonel Moody’s heroics gained wide

comment within the Army of the Cumberland making him a beloved figure with not

just his regiment, but within the army as a whole. Citing declining health,

Colonel Moody resigned his commission in May 1863 and returned to his

ministerial duties in Xenia, Ohio. He would later be awarded a brevet promotion

to brigadier general for his services at Stones River.

|

| Colonel Granville Moody 74th O.V.I. |

Even with Granville out of the Federal army, the paths of the two men would intersect again. Captain George Moody,

after joining Longstreet’s command in Georgia, followed it in its eastern

Tennessee campaign in the fall of 1863 but became sick and was left behind at Knoxville

where he was captured by Federal forces in December 1863. Captain Moody would

spend the next 15 months in Federal prisoner of war camps, even spending time at Camp Chase

where his older brother once held command.

Exchanged on March 15, 1865, Captain

Moody returned to Richmond, Virginia where he learned that he was receiving a

promotion to colonel (this never happened officially) and soon was caught up in

the retreat of the Confederate government from Richmond.

As described in his amnesty

petition, Captain Moody received verbal orders to return home to Mississippi

after learning of Lee’s surrender. At Washington,

Georgia, he met Varina Davis (First Lady of the Confederacy) who had with her

four young children and a young sister. Captain Moody traveled with them as a

protector and within a few days President Jefferson Davis joined the party,

intending to travel westward to the Trans-Mississippi Department. The party

split, Moody with Mrs. Davis and company heading south for Florida while Davis

went west. President Davis rejoined their party on May 8, 1865, stating that he

intended to “protect her from Confederate deserters and paroled soldiers who

were taking by force all the horses and mules they saw anywhere from anyone.”

But the 4th Michigan

Cavalry caught up with Davis and Moody at Irwinsville, Georgia on

the morning of May 10, 1865, and Captain Moody soon found himself a prisoner yet

again. This time he was sent to Fort McHenry, Maryland where a note from his prison

record states that Moody was “confined at this post by order of Rear Admiral

William Radford. These men were captured by B.D. Prichard, 4th

Michigan Cavalry and comprised a part of the party traveling with Jeff Davis

and family. Are to be allowed no communication by order of E.M. Stanton,

Secretary of War.”

|

| General Don Carlos Buell and staff |

This is where Granville Moody

comes back into the story. During the war, Colonel Moody and his 74th

Ohio where stationed at Nashville, Tennessee and while there, Moody became close friends with Tennessee’s war governor Andrew Johnson. As a matter of fact, Colonel Moody

was with Governor Johnson when he had his dramatic meeting with General Don

Carlos Buell in September 1862. General Braxton Bragg was moving into Kentucky

and as Buell started to follow him with the bulk of his army, Johnson feared

that Buell would leave Nashville undefended.

In alarm, the governor summoned

General Buell to the capital and the meeting occurred on September 5th.

In response to Governor Johnson’s question as to whether he intended to defend

Nashville, General Buell replied that he did not think that General Bragg’s

objective was Nashville, but “when the purpose of his crossing the Tennessee is

developed, I will be prepared to meet and fight him.”

This curt answer ruffled the

hot-tempered Tennessean. Once out of earshot, Johnson turned to Colonel Moody and

grumped, “Moody, we are sold. Buell has resolved to evacuate the city and

called upon me this morning requesting me to leave also. He has given me three

hours in which to decide. I have remonstrated against the act. I still believe

we can hold the city. What do you think Moody?” Moody replied that he would

stay with Johnson and “have faith in God that he will deliver us from falling

into the hands of the enemy.” Buell still rankled Johnson. “That man’s a

traitor; his heart is not in the cause. The government should be warned,” he

whispered. Colonel Moody offered to pray, Johnson accepted, but the irascible

governor sent a despondent letter to President Lincoln in case the prayer

misfired.

Now in July 1865 with his

brother languishing in Federal prison, Colonel Moody traveled to Washington,

D.C. to visit with his old wartime friend who was now President of the United

States. Meeting with President Johnson, Colonel Moody received a pass to visit

his brother on July 10, 1865, and within three days prevailed upon President

Johnson to release his brother from Federal custody.

“The petitioner sincerely

desires and intends to be a truly loyal citizen of the United States and has

taken the amnesty oath,” wrote Captain George Moody to President Johnson in

early August after returning to Mississippi. Colonel Moody added his voice to

his brother’s amnesty petition. “My brother stayed in my house one week on his

return to Mississippi and repeatedly assured me of his unqualified

determination to be loyal to the government of the United States," Granville stated. "I have no

doubt that my brother will fulfill his obligations in the letter and spirit of

them. I most respectfully request his pardon at as early a date as may suit

your convenience and sense of propriety.” President Johnson accepted the two

brother’s pleas and granted Captain Moody a pardon and full release.

George Moody proved

was a good as his word, working towards reconciliation with the North and

lending his support to the National Union Convention held in the summer of 1866. But he did not have long to live. On the night of Saturday, September 8, 1866,

Captain Moody was gunned down in his office by someone he had recently angered

in court. “It appears that he was sitting in his office alone about 10 o’clock

at night when he was fired upon from a window,” reported the Jackson Clarion.

“Nineteen buckshot entered his head and neck, killing him instantly. Captain

Moody was an able lawyer and a courteous gentleman. He was a brave officer,

having served with distinction through the whole of the late war. He escaped

death on the battlefield to meet it at the hands of a cowardly assassin.”

As for Colonel Granville Moody, he became a popular figure on the speaking circuit in Ohio, his lectures, and speeches on the war and Republican politics widening his fame. He retired from active ministry in 1883, wrote his memoirs entitled A Life’s Retrospect, and passed away peacefully on June 4, 1887, in Jefferson, Iowa.

Confederate Amnesty Papers for George V. Moody, M1003, National Archives & Records Administration

Civil War Service Records- Confederate-Louisiana- Captain George V. Moody, Roll 0058, National Archives & Records Administration

Moody, Granville. A Life’s Retrospect: Autobiography of Rev. Granville Moody, D.D. Cincinnati: Cranston and Stowe, 1890, pgs. 264-267

“Assassination of a Delegate to the National Union

Convention,” Daily National Intelligencer (Washington, D.C.), September

22, 1866, pg. 1

Comments

Post a Comment