Carrying Jackson off the Field at Chancellorsville

Five Days at Chancellorsville

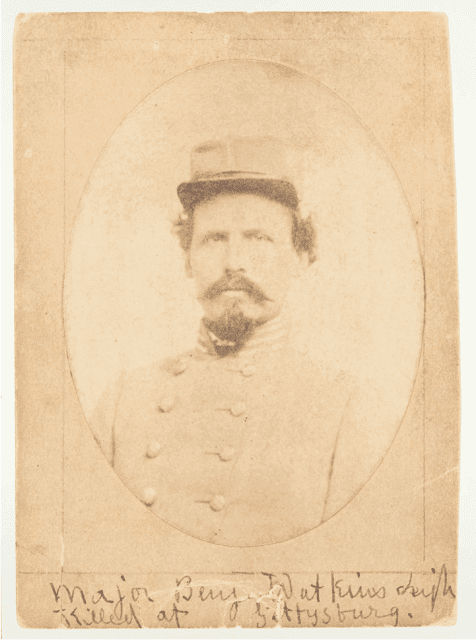

In this extraordinary account published in Volume 6 of the Southern Historical Society Papers in 1878, Major Benjamin Watkins Leigh, serving on the staff of General A.P. Hill, describes how he helped to transport General Stonewall Jackson off the battlefield at Chancellorsville after he was wounded on the night of May 2, 1863. It proved a ticklish and dangerous task.

"We had been with the General but a short time when the enemy’s battery again commenced to fire upon us," wrote Leigh. "General Jackson rose and walked a few yards leaning on my arm. His left arm had been broken above the elbow and a ball had passed through his right hand. We had not gone far when he laid down on the litter and we took it up and were carrying him along when the cannonade became so terrific that the two litter carriers abandoned the litter, leaving no one with General Jackson but Captain Smith and myself. We laid Jackson down in the middle of the road and ourselves beside him. The road was perfectly swept by grape and canister."

Leigh's letter, written only ten days after the event, is one of the earliest descriptions of the aftermath of Jackson's wounding, an event which many felt marked as the beginning of the end for the Confederacy.

Camp near Hamilton’s Crossing, Spotsylvania Courthouse, Virginia

May 12, 1863

On Friday May

1st, D.H. Hill’s, Trimble’s, and A.P. Hill’s divisions, that is to

say, all of Jackson’s corps except Early’s division, marched from the vicinity

of Hamilton’s Crossing to a point on the Plant Road about eight miles westwards

of Fredericksburg. Early’s division was left to watch a body of the enemy who

had crossed the Rappahannock at a point opposite Hamilton’s Crossing, whilst

the rest of the corps marched towards Chancellorsville, where the enemy’s main

force had been concentrated. The greater part of Anderson’s and McLaws’

divisions had been driven from their positions near Chancellorsville by the advance

of the enemy and we were marching to the support of those divisions.

Saturday May

2, 1863, found General A.P. Hill with his staff at a point about three-fourths

of a mile from Chancellorsville. General Lee, General Richard H. Anderson, General

William D. Pender, and a number of general officers were here. There was some

skirmishing going on in our front and several Minie balls from the enemy’s

skirmishers passed near us. Jackson’s corps had already started the flank

movement.

D.H. Hill’s

division under Brigadier General Robert Rodes had gotten out of our way and had

been followed by Trimble’s division under Brigadier General Raleigh Colston.

A.P. Hill’s division came last. We left the Plank Road at a point so near the

enemy that his balls whistled over our heads and marching from 9 o’clock in the

morning till 3 in the evening, a distance of 10 or 12 miles through a dense

wilderness. We found ourselves at the other end of our detour on the right

flank of the enemy and not more than three or four miles from the point at

which we had left the Plank Road.

A part of our march was

alongside of a road in plain view of the enemy and under fire from one of his

batteries. Why he did not attack us I could hardly conjecture. I have understood

that they believed we were in full retreat to the southward. It is certain they

never guessed our real design, for their right flank was assailed by us when

they so little expected an attack that many of their troops were cooking their

suppers.

Arrived at the point of our

destination and having driven in the enemy’s pickets, General Jackson made his

dispositions for the attack. It consisted simply in deploying D.H. Hill’s and

Colston’s divisions and all but two brigades of A.P. Hill’s division on each

side of the old turnpike leading to Chancellorsville, with one brigade I

believe of D.H. Hill’s division deployed across the Plank Road down the old

turnpike.

|

| General Ambrose Powell Hill |

General A.P. Hill rode down

along the road, occasionally dashing off to the right or left to see what some

particular brigade was doing and, of course, his staff accompanied him. This

state of things continued from 6 o’clock in the evening, when the attack

commenced, until 9:30. In the meantime, our troops had driven the enemy about

three or four miles towards Chancellorsville.

They had run like sheep on our

approach, throwing away their arms, knapsacks, and everything of which they

could divest themselves. They had been completely surprised. They had thrown up

entrenchments to meet an attack from the front, but as we assailed their right

flank, their entrenchments had been useless to them and they abandoned them.

They had, it is true, barricaded the roads, and some of their entrenchments were

in the right direction to meet our attack, but neither barricades nor

entrenchments enabled them to even delay our progress.

Our troops marched in line of

battle through the woods filled with thick undergrowth and across ravines at a

rapid pace for several hours. The thick woods, the combat, and the coming on of

darkness had deranged our lines and brigades, even divisions, had gotten mixed

together. In this state of things, we nevertheless pressed forward until we had

reached the brow of the declivity opposite that on which the tavern known as

Chancellorsville is situated. Here we were met by the fire of a heavy battery,

posted so as to enfilade the road. The troops halted, and Generals Jackson and

Hill rode forward, for the purpose I suppose, of making arrangements to take

the position occupied by the enemy’s battery.

At one point, we were subjected

to a severe fire from the battery, but it slackened after awhile and we pursued

our course. We soon passed our most advanced line, and were still riding down

the road, when suddenly a musketry fire opened to our right in the woods. From

whom this fire proceeded, I have never learned, but it seemed to serve as a

signal for the enemy’s battery to resume its fire. In an instant, the road was

swept by a storm of grape and canister. The shells burst above us, around us,

and amongst us.

General Hill and staff turned back towards our lines, and as we approached them, we abandoned the road which was enfiladed by the enemy’s battery. We turned off to our right in the woods. Whether it was that our troops mistook us for a body of Federal cavalry, or for some other reason, I do not know. But as we approached within 15 or 20 paces of our line, we were received with a blaze of fire. This alone, without the fire of the enemy’s battery, which still continued, would have rendered our situation a most perilous one. As it was, it seemed as if we were all doomed to destruction.

“To our great surprise our little party was fired upon by about a battalion of our troops a little to our right and to the right of the pike, the balls passing diagonally across the pike and apparently aimed at us. There seemed to be first one musketry discharged which was followed almost instantly by a volley. The single musket may have been discharged accidentally, but it seems to have been taken by the troops as a signal to announce the approach of the enemy.” ~ Captain Richard E. Wilbourn, chief signal officer on Jackson’s staff

General Hill’s

staff disappeared as if stricken by lightning. I perceived that my only hope of

escape was in getting to the ground and lying down that I might expose as

little of myself as possible to the fire of our men. I accordingly endeavored

to dismount, but my horse was rearing and plunging so violently that I could

not do so. Just at this time, he was shot, as I judged from his frantic leap,

and whether he threw men or managed to get off myself I am unable to say.

I found myself lying on the ground. I received a smart blow on the side of my head and put up my hand to see if I was wounded, but soon found I was unhurt. I laid on the ground for a short time, until our troops discounted their fire, and then arose. I saw a number of dead and dying men and horses around me, and a horse standing near me. I immediately mounted him and rode about in the woods to see if I could find General Hill. I soon found and rejoined him. We came out into the road together at that point at which we had left it, and he informed me, or I heard someone say, that he was going forward to see General Jackson who had been wounded. I perceived that almost all his staff had disappeared.

“General Hill rode up with his staff and dismounting beside Jackson, he expressed his great regret at the accident. To the question whether his wound was painful, Jackson replied “very painful” and added that his “arm was broken.” General Hill pulled off his gauntlets which were full of blood, and his saber and belt were also removed. He then seemed easier, and having swallowed a mouthful of whiskey which was held to his lips, appeared much refreshed.” ~ Captain Richard E. Wilbourn, chief signal officer on Jackson’s staff

We soon came up to where General

Jackson was and found him lying by the side of the road under a little pine

tree. General Hill directed me to go for a surgeon and an ambulance for the

general, and I hastened off for the purpose. I had not gone more than a hundred

yards when I met General Pender marching up the road with his brigade. I told

him that General Hill had sent me for a surgeon and an ambulance for General

Jackson, and he said he had his assistant surgeon Dr. Barr with his command. He

called for Dr. Barr and that gentleman speedily appeared. Dr. Barr said there

was no ambulance within a mile of the place, but that he had a litter with him.

I hastened with Dr. Barr and the litter bearers back to where I had left

General Jackson, and I also carried with me Captain James Power Smith, General

Jackson’s aide-de-camp, who had ridden up inquiring for the General. We had

been with the General but a short time when the enemy’s battery again commenced

to fire upon us.

General Jackson rose and walked

a few yards leaning on my arm. His left arm had been broken above the elbow and

a ball had passed through his right hand. We had not gone far when he laid down

on the litter and we took it up and were carrying him along when the cannonade

became so terrific that the two litter carriers abandoned the litter, leaving

no one with General Jackson but Captain Smith and myself. We laid Jackson down

in the middle of the road and ourselves beside him. The road was perfectly

swept by grape and canister. A few minutes before, it had been crowded with men

and horses and now I could see no man, beast, or thing upon it but ourselves.

After a little, General Jackson

again rose and walked a short distance to the rear, turning aside off the road,

partly because the enemy’s fire was mainly aimed at the road and partly because

the road was again becoming encumbered with infantry and artillery, and it was

easier to go through the woods. But he soon became faint, and we again put him

on the litter. I could not induce any of the men we met to act as litter

bearers until I told them it was General Jackson whom we wished to carry; I had

myself brought the litter on after the General undertook to walk a second time.

This I was reluctant to do, as we wished to conceal from the troops as long as

possible the fact of his having been wounded.

As soon, however, as I mentioned

his name, I found everyone willing to aid us. We proceeded in this way for, I

think, about half a mile. As we were going through the woods, one of the men

got his foot tangled in a grapevine and fell, letting General Jackson fall on

his broken arm. For the first time, he groaned piteously; he must have suffered

agonies. He soon recovered his composure, however, and we again took the road

to avoid a repetition of such an accident. It was a long time before we got out

of the space on which the fire of the battery seemed to be concentrated; as long

as we were in it, the shells burst around us so thick and fast that they seemed

like falling stars.

At length, I met Dr. Whitehead who, as I have since learned, had been summoned when General Jackson was found to be wounded. Dr. Whitehead had procured an ambulance in which we placed General Jackson. It was already occupied in part by a person whom I did not then recognize, but afterwards found to be Colonel Crutchfield of the artillery who had his leg broken. General Jackson at this time complained of great pain in the palm of his left hand, and repeatedly asked for spirits, of which we were unable to find any for a long time. Dr. Whitehead at length procured a bottle of whiskey. After we had gone a short distance with the General in the ambulance, we stopped at the hose of Melzei Chancellor to get some water for Jackson and Crutchfield. At Melzei Chancellor’s, Dr. Hunter McGuire, chief surgeon of Jackson’s corps, joined us and took charge of the general. Arriving at the hospital, I found Drs. Coleman, Taylor, and Fleming. They told me that General Jackson had already arrived and they also told me that it would be necessary to amputate his arm. No one at that time seemed to think that his life was in danger.

To learn more about Jackson's flank attack upon the 11th Corps, please check out these posts:

My God, what a scene it was! On the Right at Chancellorsville

Memorial Day for a Soldier: Captain Franklin J. Sauter of the 55th Ohio

Not German Poltroons: The 61st Ohio Explains Chancellorsville

All That a Soldier Can Give: Stowel Burnham at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg

Dearest Anna: A Buckeye Surgeon's Last Words to His Wife

The Greatest Move of the War: A Virginian Remembers Chancellorsville

Sources:

Letter from Major Benjamin Watkins Leigh, acting assistant adjutant general on General A.P. Hill’s staff, Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 6 (1878), pgs. 230-234

Letter from Captain Richard E. Eggleston, chief signal officer, General Thomas J. Jackson’s staff, Southern Historical Society Papers, Vol. 6 (1878), pgs. 266-269

Masters, Daniel. Army Life According to Arbaw.

Perrysburg: Columbian Arsenal Press, 2019, pg. 155 [Brand quote]

Comments

Post a Comment