Beyond the Bounds of Our Days: Garland White and the Taking of Richmond in April 1865

Today’s post features an

extraordinary letter from Chaplain Garland H. White of the 28th U.S.

Colored Troops that describes his regiment’s entry into Richmond in April 1865.

Garland White was born a slave in

1829 in Hanover Co., Virginia; he was soon sold to Robert Toombs of Georgia and

was Toombs’ body servant while Toombs served in the U.S. Senate through the

1850s. White attempted to escape in 1850 while in Washington, D.C. but was

quickly caught by slave catchers. He escaped later in the 1850s and made his

way to Canada where he became a minister to the African Methodist Episcopal

church of London, Ontario. Following the outbreak of the Civil War and the

cessation of enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act, White returned to the U.S.

and took up residence in Toledo, Ohio. White devoted his efforts to his church

and to recruiting black soldiers for the Union war effort, canvassing the state

to raise men for the 54th and 55th Massachusetts

regiments. Governor Oliver Morton of Indiana took note of White’s efforts and

requested his help with raising what became the 28th U.S. Colored

Troops.

The 28th U.S. Colored

Troops served in the eastern theater while attached to the Army of the Potomac

and took part in the siege of Petersburg and the Battle of the Crater in July

1864. It was later assigned to duty at the army supply depot at City Point,

Virginia before being assigned to the newly formed 25th Army Corps

under the command of Major General Godfrey Weitzel. As the Confederate defenses

at Petersburg collapsed in late March and early April 1865, General Weitzel was

directed to take the city of Richmond. As related in White’s letter, the men

expected to have to make a desperate assault on the Confederate fortifications

but were surprised to find that the Confederates had retreated, leaving the city

open to occupation by the 25th Army Corps.

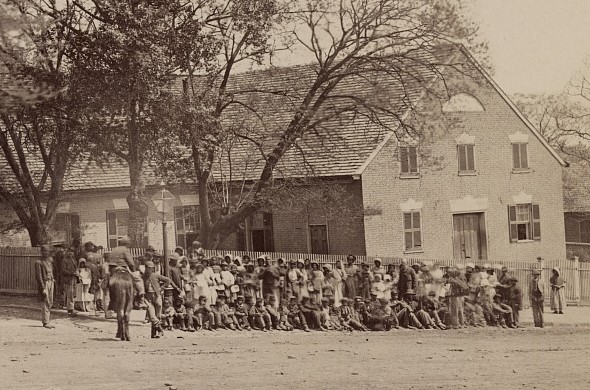

|

| White and black soldiers photographed in front of the U.S. Christian Commission in Richmond, Virginia in 1865 (Library of Congress) |

The occupation of Richmond was a

tremendous occasion for Chaplain White for a host of reasons as related in this

letter. It no doubt served as a bit of sweet justice as he had been sold in the

city of Richmond to Robert Toombs many years prior; to now return in Federal

uniform as a conqueror of the powers that once enslaved him must have been a

heady feeling. But perhaps most

poignantly was an event not described in this letter. As related in an account

to the Christian Recorder, Garland

was reunited with his mother who he had not seen for many years. “I cannot

express the joy I felt at this happy meeting of my mother and other friends,”

he wrote.

Chaplain White was a frequent

correspondent to the Christian Recorder

newspaper, but this account saw print in the April 21, 1865 edition of the Daily Toledo Blade.

City Point, Virginia

Mr.

J.C. Greiner,

April 15, 1865

It

is with great pleasure that I seat myself to write you a few lines to inform you

that the regiment is generally well.

If

there be one poor mortal in the world who should rejoice over the fall of

Richmond more than another, it is me; for by it I am satisfied to my heart’s

content. Never did I witness such a day in all my life. The Sunday night

previous to going into the city, we were called into line of battle and rested

upon our arms during the greater part of the night with the knowledge of having

to make a charge at 4 a.m. on Monday. Just before the awful hour arrived, we

heard a mighty convulsion beneath the earth and a great illumination of the

heavens above as though the last day of time’s existence had come. At this juncture,

the drum tapped, and 30,000 colored troops sprang to their feet, ready for the

awful contest.

We were for a while

unable to determine the real cause of what we had seen and heard, but before we

could definitely ascertain the true nature of the case, we received orders to

move toward the mighty works in our front and carry out the first order. Bear

in mind that in doing so we only had to advance about half a mile before discovering

that the enemy had preferred to fight white troops instead of black troops and

had removed all to Petersburg to oppose the Army of the Potomac.

On reaching their first

line of fortifications, it was plainly to be seen that they had left in great haste

and not carried off anything with them- tents, pots, kettles, cornmeal, old

clothes, guns, bayonets, everything that constituted the Rebel outfit, were

lying in great quantity all along the road to the city of Richmond. You could

not tell that they had evacuated by the appearance of anything in their lines,

and this was intended to make us believe that they were ready for battle. We

expected to have a fight at every point until we reached the city.

On approaching the city,

we saw dense columns of smoke and fire rising far above the buildings and

threatening to lay the whole place in ruins. We paid no attention to the

destroying element at this juncture for we were in search for the broken

fragments of Lee’s army which constituted a large proportion of the remaining inhabitants

and could not be detected until the colored people pointed them out to the

soldiers. It was a great sight to see a colored man arrest a white man in Richmond,

where slave pens and whipping stocks are looked upon as popular places.

The march of the colored

troops up Broad Street to Camp Lee, passing through the prominent parts of the

city all singing “John Brown’s body” was a proud one. It was a great and

glorious day to be remembered by all who witnessed it. We of the old 28th

colored regiment and other troops explained to the poorly-clad slaves who stood

in the streets in numbers that no man could number that we had left our homes

in the far distant North to come and break the chains that bound them, and to

open the doors of every slave pen and bid the inmates to come out and be

forever free under the flag they saw flying in the midst of the colored troops.

When I had been called

upon by the brave white and colored troops of the 25th Corps to make

this announcement, the boys rushed to all the slave pens (five in number) and

with the hands that caused Richmond to fall, opened the doors, never to be shut

upon one of our race. Out sprang 1,000, some being mothers with babes in their

arms who have never seen sunlight. The demonstrations of joy manifested upon

the part of the freed persons can never be described. I have been a slave and

read a great deal about slavery, but to hear those people tell what they

suffered during the war is enough to make me almost willing to deny ever having

lived in a country where such atrocious crimes were perpetrated upon a portion

of humanity.

|

| Soldiers and civilians in front of the African M.E. Church in Richmond, Virginia (Library of Congress) |

I am sorry to say that

the prejudice between the white and colored troops is greater than at any stage

of the rebellion. The former can’t bear to have it said that the colored troops

took Richmond, but I know it is so for I was there and saw myself and on the 3rd

of April 1865 delivered the first speech asserting the rights of colored people

that was ever heard in the streets of Richmond. There are many things connected

with this campaign which are of very great interest to all colored men, but I

cannot tell the fourth part. I will merely add that I believe the day has broke

and the sun begins to shine. I am glad in my heart that I joined the army. It

has been the most important schooling our people ever had, and its effects will

be seen and felt beyond the bounds of our days.

G.H. White,

Chaplain, 28th U.S.C.I.

Comments

Post a Comment