“To Fight All the Time” The 95th Ohio on A.J. Smith’s Mississippi Raid

In

the spring of 1864, the decision was made to concentrate Union forces at

various strategic points in the South to free up troops that would be added to

the primary armies of invasion in Virginia and Georgia. In western Tennessee

and northern Mississippi, this meant that the Union pulled out of Corinth,

Mississippi and allowed the area to be reclaimed by the Confederacy. Corinth’s

primary strategic value centered on the railroad junction of the Mobile &

Ohio and the Memphis & Charleston railroads. Since Federals controlled

Memphis at the western terminus and Chattanooga further east on the M&C,

Corinth was no longer deemed necessary and was abandoned. General Nathan

Bedford Forrest had been sent to Mississippi to raise forces that were tasked

with re-taking and holding this region; the area also served as a jumping off

point for Forrest to stage raids against Union supply lines in Tennessee. That

said, the primary function for the remaining Federal forces in western

Tennessee became a defensive one: to hold Memphis and keep Forrest out of

Tennessee.

To

accomplish that mission, General Samuel Sturgis led what became known as the

Guntown expedition in June 1864. His plan was to strike the Mobile & Ohio

Railroad, cut it, and draw Forrest into battle, which would serve to keep Forrest

away from Union supply lines in Tennessee that supported the Federal offensive

in Georgia. Sturgis’ subsequent mismanagement of this expedition led to his

court-martial. His army was drawn into battle piecemeal at Brice’s Crossroads

after being run for miles on the double-quick under a scorching heat; the

exhausted troops wilted under fire and were captured by the hundreds during

their retreat to Memphis. General Sturgis was loudly denounced as a drunk and a

coward and was removed from command upon his return to Memphis. The overall result

was mixed: abject failure at the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads at the cost of

nearly 3,000 casualties, but Sturgis’ raid did serve to keep Forrest engaged in

defending the Mississippi hinterlands and out of Tennessee. But the military

imperative to keep General Forrest’s forces tied up in Mississippi remained. General

William Tecumseh Sherman, commanding general of the western theater, wondered

that his troops seemed to cower before that “very devil” General Forrest, but

he had a solution in mind.

|

| Lieutenant Oscar D. Kelton, Co. A, 95th Ohio Killed in action at Brice's Crossroads (Ohio History Connection) |

In

stepped Major General Andrew Jackson Smith, an experienced and tough corps

commander from the Army of the Tennessee. Smith’s arrival in Memphis, along

with his troops who had participated in the Red River campaign, breathed fresh life

into the dispirited ranks of the Federal garrison, and Smith set out

reorganizing his forces for another go at Forrest. On July 5, 1864, as General

Grant’s army pounded away at the Petersburg defenses in Virginia and General

Sherman’s army licked its wounds after the bloody repulse at Kennesaw Mountain,

Georgia, a new expedition into northern Mississippi embarked from LaGrange, Tennessee.

Smith’s army was comprised of the remains of the Sturgis’ command and two

divisions of Smith’s newly arrived 16th Army Corps.

The

objective this time was the same as the Guntown raid: the Mobile & Ohio

railroad line that connected Columbus, Kentucky with Corinth, Mississippi and Mobile,

Alabama. General Smith planned to strike the line at some point, tear up the

railroad, provoke a response from Forrest, and then fight him on ground of

Smith’s choosing. Smith was confident that in a standup fight, his men would be

able to give the Confederates a sharp rap on the nose. Confederate forces in

the region were technically under the command of Lieutenant General Stephen D.

Lee, but it was Forrest who commanded the attention of his Federal opponents.

A

month before, the 95th Ohio had been roughly handled during General

Samuel Sturgis’s botched Guntown expedition, losing more than 200 men captured

at the Battle of Brice’s Crossroads and the ensuing disastrous retreat to

Memphis. The following accounts from Major William R. Warnock and Lawrence

Sheehan of the 95th Ohio describe their experiences under Smith’s

command at the battles of Harrisburg, Tupelo, and Old Town Creek and reflect confidence

in their new leaders. The heat was intense, water scarce, and the roads dusty,

but the Federal army went into this raid brimming with spirit. Men like A.J.

Smith and Joe Mower may have lacked Sturgis’ flair, but they more than made up

for their lack of flair in sheer competence and, as Sherman wrote, the

willingness “to fight all the time.”

|

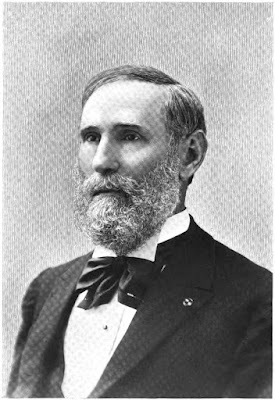

| Major William R. Warnock, 95th Ohio Infantry |

Headquarters,

95th Ohio Infantry Vols., 1st Brigade, 1st

Division, 16th Army Corps

Memphis,

Tennessee

July

22, 1864 [1]

My Dear Father: We have fought another

battle, or rather a succession of battles, and have each time gained a victory.

The effect of the Guntown disaster has been entirely removed and Lee and

Forrest have been so badly cut up that it will take them several weeks to

recruit their forces.

Our expedition left LaGrange,

Tennessee as I last wrote you on the 5th of this month and marched

by way of Ripley, Mississippi to Pontotoc meeting with little opposition. We

reached Pontotoc on the 11th and remained there until the morning of

the 13th when we started for Tupelo. During the forenoon of this

day, the Rebels made a dash on our train but were repulsed by the 4th

Brigade of our division. In the afternoon, as our brigade was marching through

a thick woods, we were fired into by a Rebel regiment which had ambushed us in

true Indian style.

[Private

Lawrence Sheehan of Co. B wrote that the regiment was marching in “close order

through a dark swamp when all at once of column of gray coats, which had been

concealed in the bushes, rose up and poured in one of the most dreadful volleys

of musketry among our ranks I ever heard. We were surprised and panic-stricken,

so much so that every man not wounded ran into the woods in confusion. Our

officers rushed into the woods entreating the men to form a line, which was

done under the heavy fire of the enemy. We then poured volley after volley into

them until all our pieces were discharged. The order was given to charge

bayonets which was done, every man hallooing to the utmost of his power. The

Rebels broke their line and ran in confusion. I had my gun shot out of my hands

while loading and the stock was broken.”][2]

The

Rebel regiment was the 2nd Tennessee Cavalry and numbered 400 men.

The 72nd Ohio and 95th Ohio, each numbering about 150

men, were ordered to charge. We drove the Rebels back through the woods about

200 yards when they were reinforced by an entire brigade and we were compelled

to fall back about 50 yards before such overwhelming numbers. By this time, the

114th Illinois Infantry, numbering about 200 men, formed in line on

our left and we were again ordered to charge. The men went into them with a

yell, and we soon had the satisfaction of seeing the Rebel brigade, which

numbered three times as many men as we had engaged, running in a manner that

somewhat consoled us for Guntown, especially as it was Bell’s brigade that had

flanked us in the Guntown fight.

|

| Major General Andrew J. Smith (Library of Congress) |

As

we were advanced on the last charge, I was on the right of our regiment and we

were about 25 yards from the Rebels where we had quite a sharp fight before

they retreated. As it was so close, I commenced firing at them with my

revolver. I had fired once and had just cocked my revolver to fire a second

time when the Rebel shot my horse. He became so unmanageable that I was obliged

to dismount and send him back to the road where he died in about half an hour.

The Rebels couldn’t stand the hot fire

we were pouring into them and in a few minutes retreated, leaving their killed

and wounded in our possession. From some of the prisoners we took, we learn

that the Rebels had made a detail to work a battery (which was following our

regiment) after they had captured it, but the battery got into so quickly and

threw the grape and canister into their ranks so fast and thick that they were

glad to get out of range. The Rebels lost a good many men and didn’t gain a

single point. The adjutant of our regiment was wounded in the jaw but not

dangerously. Lieutenant Colonel Jefferson Brumback had his horse shot under him

about 10 minutes before mine was shot. The 95th Ohio had eight men

wounded and two will probably die. We then marched to a point near Tupelo and

bivouacked for the night.

Early on the night of the 14th

our pickets commenced skirmishing and our generals prepared for a fight. The

men soon saw, by the way they were handled, that A.J. Smith and Joe Mower were

equal to Forrest and his generals, and consequently went into the fight with a

hearty good will and felt confident of success. Before 7 a.m., the engagement

became general and lasted only three hours. The Rebels made charge after charge

on our position but were repulsed with terrible slaughter. We had an excellent

position and one which protected our men and as the Rebels seemed very anxious

to attack us, Generals Smith and Mower let the men lie down in position and

shot down the Rebels as they advanced across the open fields. Our artillery was

posted in excellent position and as the enemy made their repeated charges did

great execution.

[Lawrence

Sheehan related that “the long line of graybacks came out of the woods through

an open field, their officers waving their swords and all yelling their best.

General Mower let them come until within about 20 steps of our line when we

rose up and poured the cold lead into their ranks, our artillery opening at the

same time. It was a fearful sight. Their ranks were cut to pieces and what was

left retreated perfectly panic-stricken and demoralized. Where their lines had

formed was covered with dead and mangled bodies, some with their legs off, some

yet alive with their bowels hanging out, some with their arms torn off at their

shoulders, and in some places the blood was shoe-mouth deep. The Rebel General

Faulkner was left dead on the field; I saw him and got a button off his coat.”]

A little before 10 a.m., the Rebels

abandoned their attempts to drive us from position and retreated, leaving their

killed and wounded in our possession. We advanced the lines about half a mile

but the Rebels were too severely punished to continue the attack. I went over the

battle grounds, and I must say I never saw as many dead Rebels in as small a

space of ground as there was there. We learned from our Rebel prisoners that

their officers had told them that we were all 100-days’ men and would run at

the first fire if they would only put on a bold front and charge, which is no

doubt the reason of their attacking us so boldly in our position. The Rebels

admit a loss of 2,400 killed and wounded but I should not be surprised that it

is even greater. [Official Confederate losses came in at roughly 1,250 killed

and wounded with another 50 missing with Forrest lamenting that the effort to drive Smith from Mississippi "cost the best blood of the South."]

|

| Lieutenant Henry Warren Phelps, Co. H, 95th Ohio. A devoted historian, Phelps wrote extensively of his regiment's wartime service throughout his lengthy career. |

On the 15th, we were busily

engaged in caring for the wounded and burying the dead. On the morning of the

16th, as we had but three days’ half rations for our army and were four

days’ march from our base of supplies, we commenced our march to LaGrange. Our

division, General Mower’s, was in the rear and our brigade in the rear of the

division. One half of our army had marched out on the road and nearly all of

our train had started. The Rebels saw this and, thinking we had only a cavalry

rear guard, charged across the same fields in which they had been so badly

repulsed on the 14th. Our artillery opened on them with grape and

canister and our infantry poured a deadly volley into them. They fell back just

as they had on the day of the battle. The Second Brigade then made a charge and

drove the Rebels entirely back from their position.

We then marched about five miles and

went into camp near a creek. Just as our brigade, which was in the rear, had

crossed the creek, the Rebels commenced to shell our camp. We were immediately

formed in line of battle and Colonel McMillen ordered an advance. After

recrossing the creek, our brigade charged on the Rebels and drove them back in

great confusion. The lost quite heavily in this engagement and if our men had

not been so much exhausted, we would have captured the Rebel battery. After

this we were not molested by any demonstrations of the enemy. They were wary of

being led into the some trap and captured as some men we captured in the last

fight thought our brigade must have been formed in line of battle in the woods

waiting for them to come up as we advanced so quickly after they had shelled

the camp.

We then marched by easy stages to

LaGrange where we arrived on the 21st and came by railroad to

Memphis today. Our force consisted of about 12,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry,

the whole commanded by Major General Andrew J. Smith assisted by Generals

Mower, Grierson, and Colonel Moore. Our total loss in killed, wounded, and

missing does not exceed 500 and will probably be not more than 400. The Rebels

were commanded by Generals Stephen D. Lee, Nathan B. Forrest, Abraham Buford,

and others. It was a terrible punishment to the Rebels and if we had only been

able to supply ourselves with rations, we could have marched to Mobile.

[1]

Letter from Major William R. Warnock, 95th Ohio Infantry, Urbana Citizen & Gazette (Ohio),

August 4, 1864, pg. 2

[2]

Letter from Private Lawrence Sheehan, Co. B, 95th Ohio, Springfield Republic (Ohio), August 10,

1864, pg. 1

Comments

Post a Comment