Breaking the Clouds of Gloom: The 83rd Ohio at Arkansas Post

It was the afternoon of January 11, 1863, and after an

initial repulse from Fort Hindman, General A.J. Smith rode amongst his troops

steeling them for the task ahead.

“There was no

panic, nobody was scared, all wondering why we fell back,” recalled Orderly Sergeant

Thomas B. Marshall of the 83rd Ohio. “General A.J. Smith and his

staff rode to and fro, pistols in hand, to realign the troops and start them in

again and oh how he swore! For artistic and effective profanity, General A.J.

Smith had no superior and coming from him, it never sounded wicked. His every

word hit the nail on the head while all the air was blue. We soon reformed and

moved forward in good order, going to the edge of the slashing and to the top

of the little rise. The fort was now in plain sight and the bullets were

singing their songs as they flew both ways. We dropped to the ground, loaded,

and fired as fast as we could, or when we could see something to shoot at, all

the time edging towards the fort. Most of the artillery had been silenced so

that we had only musketry to face.”

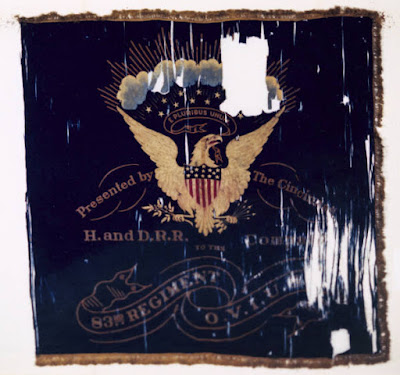

The 83rd Ohio, later called the Greyhound Regiment, along with the other regiments of General Stephen G. Burbridge’s brigade of A.J. Smith’s division, reformed under the barrage of Smith’s profanity, eventually took Fort Hindman later that afternoon. As Sergeant Marshall recalled, the victory at Arkansas Post was the “first break in the great cloud of gloom which had settled over the land since the preceding summer.” Sergeant Marshall’s detailed account of the Battle of Arkansas Post is culled from his regimental history of the 83rd Ohio published in Cincinnati by the regimental association in 1912.

Sergeant Marshall starts the story of the capture of Arkansas Post on the morning of January 2, 1863, aboard a steamer in the Yazoo River. His regiment had pulled out the night before from Chickasaw Bayou near Vicksburg and now, safely aboard the steamboat, morale plummeted as the men pondered the army’s next move.

We steamed out of the Yazoo and

turned up stream for some destination unknown to us. Fuel for the boilers was

very scarce and it was part of our duty to bring to the riverbank rail fences,

parts of trees, anything, and chop them into convenient lengths and pile them

on board for the furnaces. It was not always wood that demanded our care, for

sometimes when we steamed away a mound or two of fresh earth was seen, silent

witnesses of grief in some home. It was during these days, from the time of leaving

the Yazoo until we arrived at White River, that the army became very much

discouraged. It got to be a general thing for men of all companies to go

foraging, to allow themselves to be captured and paroled, so as to have a

chance to get home. Sometimes the parole would be accepted from a woman, at

least it was so reported. For several days, we kept this up so as to get a

surplus of wood in time of need. While we were busily engaged one day in the

rail business, Archie Young said, “I don’t mind the work, but it is the sin of

it. Think of it! If it was only night, I would not care so much, but in broad

daylight when everybody is looking, it makes me blush.”

|

| First Sergeant Thomas B. Marshall, Co. K, 83rd O.V.I. |

Early on the 9th

of January we were told we must have 20 cords of wood on board before

breakfast. Well, we did it and started up White River, which my diary says was “the

crookedest stream in seven states.” At 5 o’clock, we reached the “cut off”

which was a safe passage into the Arkansas River. This river empties into the

Mississippi River some 25 or 30 miles below the mouth of the White River. It

was far easier to steam up the broad Mississippi and use this cut off than to

attempt the crooked Arkansas, especially when there was a large sand bar at its

mouth. All this time, our destination was well known to our general officers,

and it was Fort Hindman, but always called by us Arkansas Post. Being in the

Arkansas River we would have threatened Little Rock had it not been for the

above-named fort.

|

| Lieutenant Colonel William H. Baldwin, 83rd O.V.I. |

A little after

noon on January 10th, we disembarked and marched about three miles

and halted in front of a deserted Rebel stockade and prepared to pass the night.

We were not allowed to stay long, however, and after dark were quietly moved

forward and laid down in line of battle. It was a very cold night, and many

were far from comfortable to say the least. We were called up early of the 11th,

moved forward, and ordered to lie down.

We were now getting very close to the fort, and they began to hunt for

us with their artillery. Balls came screeching through the woods occasionally

with limbs falling in profusion. We were in range all night if the enemy had

only known it.

The forenoon passed

in making preparation and getting into position for the assault. As soon as the

land forces were ready, the gunboats moved up in range and opened fire on the

water side while the land batteries limbered up and added their powers. Soon

the Rebel artillery was practically silenced and the infantry moving forward

began with musketry. The 83rd Ohio was placed on the left of the

first line of Smith’s Division, and we were ordered forward with instructions

to keep in line with the 16th and 67th Indiana regiments

on our right. The woods were thick with underbrush and with a small stream

flowing toward the river, the line was badly broken. We finally reached a fence

at the edge of the woods and climbing over it, moved forward, and opened fire.

From some cause, the Indiana regiments on our right broke and fell back and we

followed as we had been ordered. There was no panic, nobody was scared, all

wondering why we fell back.

|

| General Andrew Jackson Smith "For artistic and effective profanity, General A.J. Smith had no superior." |

General A.J.

Smith and his staff rode to and fro, pistols in hand, to realign the troops and

start them in again and oh how he swore! For artistic and effective profanity,

General A.J. Smith had no superior and coming from him, it never sounded

wicked. His every word hit the nail on the head while all the air was blue. We

soon reformed and moved forward in good order, going to the edge of the

slashing and to the top of the little rise. The fort was now in plain sight and

the bullets were singing their songs as they flew both ways. We dropped to the

ground, loaded, and fired as fast as we could, or when we could see something to

shoot at, all the time edging towards the fort. Most of the artillery had been

silenced so that we had only musketry to face.

|

| First Lieutenant Gershom L. Tomlinson, Co. D, 83rd O.V.I. |

A force also came up on the south side of the river and with their artillery knocked about two feet off the muzzle of a large pivot gun in the southwest corner of the fort. We were reinforced by the other brigade and allowed to be quiet for a while. We did not lie idle very long but moved forward and taking the front of the line, kept up a steady fire so that the enemy could not even look over the parapet. At one time there was a lull, and all rose up to see the cause, but when the bees began to hum again, we dropped down and kept up our steady fire.

“I never heard such cannonading in my life. The ground fairly shook, the air was filled with smoke. The Rebels replied vigorously and the shells fell thick and fast. After a while the fire from the fort almost ceased and musketry commenced on our right. Soon the word came to advance, and we moved into the open field on double quick. We were then in the rear of the 83rd Ohio; they faltered and partially broke, we passed by them and were in the advance then dropped down, the balls falling like hail. Some of our regiment came up behind us and fired so wildly that we were placed between two fires.” ~ unknown member of 96th Ohio

The enemy

seemed determined to hold the fort and fought like so many tigers. We kept our

lines formed as well as we could. We were about out of ammunition, and none

could be gotten to us. The 96th Ohio and the 77th

Illinois came to relieve us, but the three regiments were so badly mixed up

that no one could tell one from the other, and no commands could bring order

out of chaos. This may not be understood by those who never saw a real battle

but have formed ideas from pictures which put the soldiers all in line. In

modern warfare, such a line would be cut down like grass before a scythe. When

the real battle is on, while all try to keep together, everyone looks out for

himself. A stump or tree is always made use of, and under a heavy fire one of

the best points about a good soldier is to be able to save himself while he

fights and kills the enemy. The regiment was never under a heavier fire than

for the few hours on that day.

This terrible

fighting did not cease until 5 o’clock in the afternoon when, without warning,

white flags were hoisted above the works of the enemy. All firing instantly

ceased. Cheer upon cheer followed, while all order being cast aside, every

effort was made by everyone to be the first in the fort. The flag of the 83rd

Ohio was the first one planted on the rampart. For two hours and 50 minutes we

had been under fire and having received this baptism, we were full-fledged

soldiers. The regiment went into the engagement with about 400 men and lost ten

killed and 80 wounded, over 20%. The regiment was honorably mentioned in official

reports, while the Ohio legislature showed its appreciation by a unanimous vote

of thanks. This victory was the first break in the great cloud of gloom which

had settled over the land since the preceding summer.

It would be scarcely possible to give an accurate description of the inside of the fort. The shot and shell had torn it all to pieces. Dead and wounded were everywhere. The casemate with its large gun was rendered utterly useless; headquarters buildings were totally wrecked, field artillery dismounted. The loss in the fort was 50 killed, 300 wounded, and 6,000 prisoners, 1,000 mules, and large amount of commissary stores. The regiment remained on the ground during the 12th and 13th, burying the dead, caring for the wounded, leveling the earthworks, and transferring the captured property to the boats.

Marshall, Thomas B. History of the 83rd Ohio

Volunteer Infantry, The Greyhound Regiment. Cincinnati: The 83rd

Ohio Volunteer Infantry Association, 1912, pgs. 54-59

Letter from unknown member of 96th Ohio Volunteer

Infantry, Delaware Gazette (Ohio), January 30, 1863, pg. 3

Comments

Post a Comment