Hooping, Yelling, and Rushing Around Like Madmen: An Indianan Captured on Wheeler's Ride

The supply wagons of General Alexander McCook's corps had been sitting near LaVergne for hours on December 30, 1862 awaiting orders to move forward. Ten miles south on the Nashville Pike, the Federal army was closing in on Murfreesboro, but the long hours of waiting made the train guards and teamsters nervous. Shortly after 2 o'clock, things got beautifully worse as Ordnance Sergeant John J. Gallagher of the 81st Indiana later recalled.

"About 2 o'clock some of the boys went to the wagons to lay down and take a nap. As they were fixing to make themselves comfortable, they looked out from the back of the wagons toward the road and beheld a sight that caused their hearts to beat quickly, for as far as they could see there was nothing but the enemy's cavalry galloping about, dressed in the well-known butternut clothing, hooping, yelling and rushing around like madmen in every direction. The boys seized their guns and ran to the nearest house and breathlessly awaited further developments. No one seemed to have any command or authority over the men or train," he wrote.

Within minutes, Gallagher and most of the 150 supply wagons near town had been captured. Wheeler's men took particular delight in capturing McCook's headquarters wagon including a Christmas turkey and one of the General's oversizing frock coats, along with bundles of military papers including ordnance reports and personal correspondence. As for Gallagher, his captors ordered him to mount a mule and follow along, giving him the opportunity to witness the rest of Wheeler's raid.

Sergeant Gallagher's account of Wheeler's raid was originally published in George W. Morris' regimental history of the 81st Indiana published in 1901.

When the regiment was getting ready to leave Nashville there were some changes, as such a move made it necessary. Corporal John J. Gallagher, of Co. B, was appointed ordnance sergeant, and all the old guns, accouterments, etc., belonging to the regiment was turned over to him, as well as the regimental ammunition. Everything was loaded into wagons and ordered inside of the entrenchments at Nashville. There were several wagons in the detail, for they had all the regimental baggage along with the balance.

After remaining in Nashville until December 29th

they started out for the regiment. The

train of wagons numbered about three hundred.

When the train left Nashville, it was a beautiful morning and everything

looked bright and cheerful. They traveled all day until about two or three

o'clock, when they reached a little town about fifteen miles from Nashville

[LaVergne]. Here the train halted and

corralled for the night in the town, the inhabitants having left, the houses

being deserted. As there were two wagons from our regiment, they drove up

alongside of a one-story frame house and the drivers commenced unharnessing the

mules. While doing so, orders came to

send a wagon back on the road six miles for corn for forage, which was in a

camp lately held by the enemy. Sergeant

Gallagher was one of the detail to go back with the wagons. The order came from an unauthorized source,

but the boys did not refuse to go. When

they got out on the pike, they found several other wagons detailed for the same

purpose, each containing a guard. They went the six miles in a sweeping gallop

back toward Nashville, one of the hardest wagon rides they had ever

experienced, and they all felt as if every bone in their bodies were broken.

They arrived at the camp and drove into the

field, found the corn in large quantities posted their pickets at the proper

distance, and commenced loading as quickly as possible. In a few moments their wagons were loaded,

and they drove out on the pike and hurried back to camp. In a short time,

supper was ready, and, having a good appetite from their pleasant ride, they

did full justice to it. They soon

retired to rest, taking up their quarters in the wagons. Of course, they did not sleep much. They were

up early in the morning and found a drizzling rain falling, making everything

look miserable. It made the boys feel gloomy, but after breakfast everything

was gotten ready to move in case an order came to do so, but they laid there

hour after hour and no order came. Of

course, the boys could not account for it. They could hear of no fighting in

front, yet there was no order to move.

The dinner hour arrived, so they sat down to

dinner, and after dinner wandered around and smoked their pipes to help pass

away the time. Still no order came to

move. About 2 o'clock some of the boys

went to the wagons to lay down and take a nap.

As they were fixing to make themselves comfortable, they looked out from

the back of the wagons toward the road and beheld a sight that caused their

hearts to beat quickly, for as far as they could see there was nothing but the

enemy's cavalry galloping about, dressed in the well-known butternut clothing,

hooping, yelling and rushing around like madmen in every direction. The boys seized their guns and ran to the

nearest house and breathlessly awaited further developments. No one seemed to

have any command or authority over the men or train.

In the midst of the excitement some of the boys

found they had no caps on their guns, although when they started, they had

their pouches full. They were soon furnished with plenty of caps. They were

huddled together on the porch of the house, having full view of the enemy, who

were yelling and going in every direction and firing at the wagons of the train. Someone in the party counseled prudence and

not to fire, as we were so largely outnumbered, and it would go hard with us if

we did so. Before we could decide what

to do, a company of the enemy's cavalry came dashing down upon us with pistols

and carbines in both hands, pointing at us and yelling like fiends, ordering us

with curses to surrender and march out from where we were posted, and do so as

quickly as possible. All this took place

in less time than it takes to write it.

We were ordered, in no very polite manner, to march quickly up to a hill

a few hundred yards in our front.

|

| 81st Indiana monument at Chickamauga |

Our men could be seen running in all directions,

and we could see the enemy in every direction galloping about, showing plainly

that we were surrounded before the charge was made upon us. While we were hurrying toward the hill, we

were stopped by several Rebs, who demanded to know if we had any pistols about

us, as they were anxious to get them. They did not make much off of us in that

line. When we were first taken prisoners

we were ordered to throw down our arms, but some of the boys did not hear the

order at the time, and were carrying them with them toward the hill when they

were stopped by the Rebs, who informed them, in their usual polite style, that

if they did not drop their guns they would soon hear from them in another

manner not pleasant to our feelings, and of course the boys, not wishing to put

them to any trouble on their account, threw the guns down, and their

accouterments also.

On arriving at the top of the hill we came upon a

line of our men drawn up in two ranks.

We were ordered to fall in with them, and a Rebel harangue was made to

us by Colonel [William S.] Hawkins, C. S. A. The

speech was made in a quick, excited manner and we were ordered to hold up our

right hands and swear that we would not take up arms against the Southern

Confederacy until honorably exchanged.

As soon as this was done the men broke ranks and scattered in every

direction. Everything was done in the midst of excitement. Rebel horsemen kept

yelling and riding in every direction.

By this time all of our trains were fired and burning rapidly. We asked permission from a Confederate

officer if we could go down to our wagons and secure some of our things. Our request was granted, and we flew, not

having time to run, but found them all in a blaze. One of our wagons contained our headquarters,

baggage and equipment, together with the adjutant's desk containing the books and papers of the regiment, as well as

the regimental state colors. All of

which were destroyed. We endeavored to

save our knapsacks but found them laying by the side of the wagons torn open

and the contents confiscated by some lucky Reb, leaving behind only some

blankets, and other little notions they did not want.

While we were picking at these a Reb came along

and was going to deprive us of them on the supposition, we supposed, that to

the victor belongs the spoils, but with some little persuasion we were

permitted to keep them but it was very little benefit we derived from them

after all. While packing them up we were

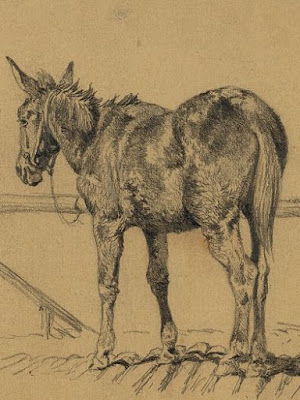

ordered by a petty, saucy-looking Reb to go and catch a mule, and be quick

about it, too. As some of the boys did

not wish to misunderstand him, they asked him what he wanted, when he informed

us in a style not to be misunderstood, with a volley of words not necessary to

mention here, that we had better hurry, or we should hear something (the enemy

had a very polite way of speaking to prisoners during that time).

So looking around, we saw several of the men

catching mules and mounting them, and not wishing to trouble the gentleman any

more we ran to where some mules were tied and unloosed them, threw our blankets

on them, and, after several attempts, mounted them. It being the first time some of us had the

honor of appearing on a mule, some of the mules having nothing but halters

around their necks, we had quite a time to manage them, as we had no chance to

get a bridle. After we were mounted it

took some time to get his muleship to start, but after sundry and repeated

kicks, vigorously applied with our heels to his sides, given under the greatest

excitement of mind at the time, we got them to move out toward the pike, where

we found a number of our men halted under guard and all on mules, waiting for further

orders.

A gloomy feeling crept over us by this time, for

we saw, a fair prospect of a long ride with the Rebs and perhaps prison in the

end, which was under the circumstances, calculated to make us feel gloomy. Some of the boys never having rode a mile on

horseback in their lives, they could not help feeling that it would go hard

with them galloping through woods and fields on the back of a mule without

saddle or bridle, surrounded with rough men, and enemies at that. Shortly after we joined the prisoners we were

ordered forward under guard toward the head of the column. As far as we could see there were enemies in

every direction. They were at halt while we were moving forward. Some of them were in crowds in the woods,

around boxes of plunder taken from our trains.

Clothing was being distributed among some of them, and in every

direction could be seen broken trunks, valises, etc., that belonged to our

officers, laying scattered over the ground as we rode along. We ran across some pretty rough Rebs. We were cursed every once in a while, and

what little things we had were taken from us.

There was no help for it; it was useless to appeal to their officers. Every few minutes the officer of the guard

would shout out, "Close up prisoners!" when we would all start off in

a gallop for a short distance, and then dwindle down to a slow trot. At last, we arrived at the head of the

column, when we were ordered to halt.

We could not help but smile at some of

our crowd, for they looked so ridiculous. Sergeant Lahne, of our regiment, was

a very tall man -- over six feet and very lean.

He had unfortunately mounted a very small mule and the consequence was

his feet nearly touched the ground, and his whole attention seemed to be

engaged in steering clear of stumps and trees.

While we were halted some of the Rebs talked with us and asked us what

we came down there for, and if we thought they had horns growing out of their

heads. They said we were being whipped

all around, that we could never subdue the South, and a lot of other

stuff. We answered several of their

questions, but as several more of their companions joined in, we thought it

best to dry, up and say nothing. One of them wanted to buy Neil McClellan's

boots, but he said he did not want to sell, for if he had he would have been

compelled to take pay in Confederate script.

A great many of them were dressed in citizens'

clothes, which caused us to, suppose that a number of the citizens in the

immediate vicinity of Nashville had purposely joined this gang to war upon our

trains in the rear, of our army men who no doubt bore a good loyal name on the

books of the provost marshal at Nashville.

Our supposition proved to be true in some respects, because the next

day, whenever we passed a home, the men in citizens' clothes would drop from

the ranks, ride up and dismount and that was the last we would see of, them.

There was no honor among them; they were a perfect set of cutthroats; nothing

was disgraceful with them as long as it benefited their cause.

When we halted, we were placed in the

center of the column. There were about 46

prisoners altogether, mostly teamsters.

For a while we moved pretty rapidly through the woods. After we had ridden about two hours our legs

became very painful. We came across one

man from northern Alabama who said that he held out for the Union as long as

possible, but when his state seceded he went with her, and now he felt sure the

South would succeed. He seemed to be a Christian man, and from his conversation

we thought a kindhearted man, and, although we were enemies, we could not help

but respect him.

Most of the time we rode very fast, but just a

little before dark we came to a halt.

Our companions told us to look through the timber and we would see

something, as they were about to make a charge. We did so and could see a small

town (which we afterward learned was Nolensville), and near it were five or six

United States army wagons. We could see

the boys in blue walking about, and some of them appeared to be getting

supper. Presently a long yell was given

and a long line of Rebel cavalry charged down upon them and their wagons. They

ran in every direction, but it was in vain, for what was a handful of men

against thousands of the enemy. No doubt

the enemy felt glorious over such a charge as that, and some of them did, too,

because shortly afterward we saw several of them under the influence of whiskey

taken from a sutler's wagon that was captured with the rest. These wagons were all burnt the same as were

ours; and with a small addition of fresh prisoners, we took the road

again.

When we got on the pike, we started off on a

regular gallop, which continued for some time, then we wheeled into the woods

again and rode some distance, it being by this time nearly dark. Just about dark we arrived at the camp they

had picked out for the night. The night was very cold and quite a number of

fires were burning in every direction. In a few moments we were told to march

up into a field a short distance and dismount and build fires. A guard was detailed to watch us for the

night. Some of the men got rails, and

our fires were soon burning. All the mules were tied to a fence close at

hand. Most of the boys were nearly

famished for water. This was certainly the most exciting day we had spent in

the army so far; we felt so stiff and sore from riding that we could hardly

move about. We had eaten nothing since

dinner and our present surroundings did not give us any appetite. We did not

have much for supper; a few crackers and a little piece of bacon, that was

captured from us, was all we had.

Some of the enemies that were dressed in our

clothes came and talked with us to see what they could find out, thinking that

they could deceive us because they were dressed in blue, but they were

mistaken. General Rosecrans soon

afterward put a stop to it by issuing an order that all Rebs caught in our

uniform would be hung, which was, a good thing at the time. We laid down by the fire and tried to sleep,

the night being very cold, and, having no blankets, we felt chilly. About the time we began to doze, an order

came to jump up and be ready to March; so, we got up, feeling so stiff we could

hardly move. It was about 2 o'clock in

the morning, and the last day of the year 1862.

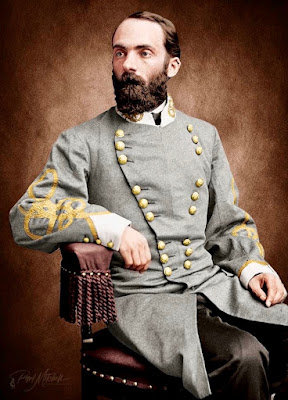

|

| Colonel John Timberlake 81st Indiana Infantry |

There was continued firing of guns all

night on their outposts, for what reason we could not find out. We began to feel interested in what they were

going to do with us. Some said we would

be paroled and others said they would send us to Richmond, Va. We were kept in a state of suspense until the

order came to mount a mule and march out.

When we got out on the road we halted and stayed there several hours.

Finally, the order came to move forward.

Some of the boys were so sore and stiff they could not ride on the sharp

backs of mules. When daylight came,

Sergeant Gallagher asked an officer, who seemed to be in command, if he could

not get a saddle as he was notable to ride in his present condition. He said he would not. After riding for several miles, he got off of

his mule and tried to walk, but as soon as he got on the ground, he was

ordered, with curses, to mount again, and as his mule was gone, he could not do

so, but just then Mell Bruner came along and took him up on his mule behind

him. That relieved him some, and of

course, being with one of his own company, and from the same town, he felt more

like he was at home, or, at least, among friends; but they did not fare so

well.

Bruner had to get off and walk, so that left him on

the mule by himself. In a short time, he

felt so badly that he had to get off of that mule, but no sooner was he off

than he was cursed and given orders to mount again, and that quickly. Not having any mule to mount, one was brought

to him. He got on it and soon caught up, but in a short time he was feeling so

badly that he could not stay on him. He got off again, another mule was brought

and one of the toughest Rebs in the gang took charge of him. After cursing him

for some time, he ordered him to mount.

He told him he could not, as felt too weak. They came to a house and he ordered one of

his men to get a bridle and saddle.

After it was put on the mule he was ordered to mount, telling him if he

got off again, he would give him the contents of his gun. He did not ride over five hundred yards

before he felt so badly that he fell off of the mule on the side of the road.

One of the officers came back and asked what was the matter; they told him that

a prisoner was keeping them behind. The officer proved to be General Wheeler,

their commander. Just then another mule

came along, and he mounted him and managed to catch up with the other

prisoners. They were all glad to see

him, especially Bruner. They all rode on

until about 11 a. m., when they came to a large farmhouse. A halt was made and they were brought into a

large yard and ordered to dismount and bring corn for the mules.

While they were there, an officer came

to some of the boys and took them into the house, where they found a lot of Rebel

officers and some of our men. An officer

asked if any of them could write, and they told him they could. So, he gave them a copy of a parole and told

them to write some copies off for the men, and he would sign them. After they had written about a dozen they

took them to the officer, whose name was Hawkins. While the paroles were being signed, some of

the boys both Union and Rebel, were in the cook house, where a Negro woman was

cooking some corn dodgers for them. On

each side of the stove were Union and Rebel soldiers watching closely the cakes

and before they were hardly done, either one or the other would grab them and

run off. The old cook would sometimes

slap their knuckles with her ladle for being so smart; the Union boys thought

that she generally favored them.

An officer came out and told them that

General Wheeler's orders were that they should give up their overcoats and

blankets. They did not like that order

very much, so some of them played off sick and got to keep them. They were then

ordered to fall into line, and a speech was made to them, informing them they

were regular prisoners of war and that they must respect their paroles or

suffer the consequences, and that they had better remain at home than to come down

there burning and pillaging; that they could never conquer the South. They were

then told that they had better march back to Nashville and that they had better

have a white flag ahead of them, as the road was full of guerrillas, who, if

they did not see the flag, might fire on them.

|

| Orderly Sergeant Edmund T. Bower Co. I, 81st Indiana |

While all this was taking place the Battle

of Stones River was going on, for they could hear firing in front. Several Rebel

horsemen rode up, their horses covered with foam, and said the Confederate Army

was driving Rosecrans, that Cheatham was driving his right wing back, and

before night the whole Yankee Army would be in Nashville. Our men were ordered

to move out on the road Nashville. When

they started, a drummer boy fixed a white handkerchief to a pole and marched

ahead of them, and they bade a glad farewell to the Rebel cause. Before they left, they noticed quite a

commotion among them, which they supposed was caused by some news they had

gotten from the battlefield. Our men had

been with them about 24 hours, and they said there was more misery and

suffering crammed into that short space of time than they ever endured in all

their lives.

The Federals were taken prisoners about 3 p. m.,

December 30, 1862, and up to the time they were paroled had ridden 60 miles. After

getting out on the pike they found there were 46 of them, all told privates,

teamsters, wagon masters, drummer boys, non-commissioned officers and a

captain. They formed themselves in

company order, and, with the white flag flying before them, took up their march

to Nashville, some 30 miles away. They

could still hear the sound of the battle that was going on at that time. Toward night they stopped at a log house on

the road and stayed all night, some of the boys going to a neighboring straw

stack and getting straw, which made comfortable beds. The night was pretty cold, but they had a

good fire in the fireplace,

The next morning, New Year's Day, they

were on the road again, and arrived on the outskirts of the city in due time

but were stopped by the pickets. They

stated to the guard who they were, and were ordered to report to the provost

marshal, who ordered them to report to the barracks, which was a large brick

building, known as the Zollicoffer House.

While they were in Nashville they had a visit from two members of the

regiment-James LeClare and Peter Bohart -- who were, wounded at Stone River,

and shortly afterward Lieutenant Colonel Timberlake called on them.

Source:

Morris,

George W. History of the 81st

Regiment of Indiana Volunteer Infantry in the Great War of the Rebellion, l86l

to l865...A Regimental Roster, Prison Life, Adventures, Etc. Louisville: Franklin, 1901

Comments

Post a Comment