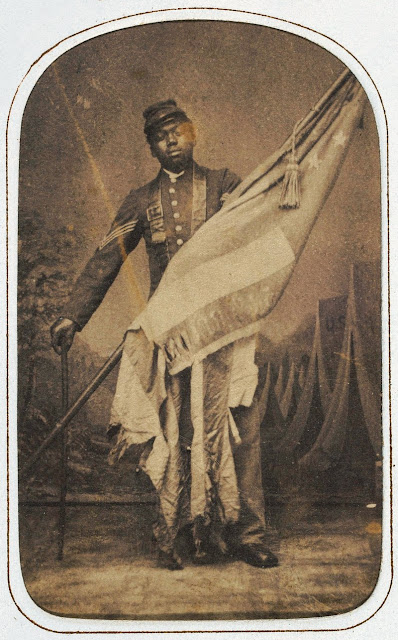

The Flag Never Touched The Ground: William Carney at Battery Wagner

The battle still raged at Battery Wagner as Captain Luis

Emilio, the ranking surviving officer of the 54th Massachusetts, rallied the battered survivors of the failed charge behind a sand

embankment. The regiment had suffered grievously: Colonel Shaw was missing and

presumed dead, hundreds of men were missing, at least 50 more had returned with

wounds ranging from the trivial to the ghastly, and the pride of the regiment,

its state and national colors were missing. One of the color guards had managed

to bring off the staff of the state colors, but the silk flag itself was

missing.

Out of the gloom, the men of the

regiment spied a man stumbling towards the line carrying a flag; to their

surprise, they found that it was Sergeant William H. Carney of Co. C bringing

back the national colors of the 54th through a hail of bullets and shells.

The Virginia-born sergeant had been wounded once in the left hip, once in the

right leg, once through the chest, once more through the right arm, and finally

a bullet grazed his head. His blue uniform was riddled with bullet holes and soaked with blood,

but he still grasped the colors firmly and his comrades broke into cheers once he

presented the colors to Captain Emilio. “Boys, I only did my duty,” he said

plainly. “The flag never touched the ground.”

In late 1892, Sergeant Carney wrote the following account to the National Tribune detailing his experiences at Fort Wagner in response to a prior article written by Sergeant Solomon C. Miller of Co. H of the 76th Pennsylvania, the Keystone Zouaves. Carney would be awarded the Medal of Honor on May 23, 1900 for his actions at Battery Wagner, the citation reading “when the color sergeant was shot down, this soldier grasped the flag, led the way to the parapet, and planted the colors thereon. When the troops fell back, he brought off the flag, under a fierce fire in which he was twice severely wounded.” Sergeant Carney was the first African American soldier to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

In an article speaking of the

charge on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863, Sergeant S.C. Miller of Co. H of the 76th

Pennsylvania [Keystone Zouaves] says he was there on July 11th and

on the 18th carrying the colors of his regiment which is all right.

Then he also says he does not want to rob Sergeant Carney of his honors. I

would like to ask the sergeant how near he got to the fort on the night of July

18 because I shall tell just how near I got.

While on the charge, he will

remember that we came to the rifle pits where the pickets were stationed

outside the fort and just after crossing the rifle pit, I found the national

colors of my regiment unguarded; that is to say that the color sergeant [John

Wall] had fallen into the rifle pit and as the regiment rushed on, he was

trampled over so far as I know. I must submit that there was no time for

investigation there at that time, and I did not attempt an investigation, but

seeing the colors, I grabbed them and rushed on with my regiment and although

the sergeant says no men reached the fort that night, I can describe the manner

in which the 54th with Colonel Shaw, Carney, and the rest actually

reached not near the slopes, but the ramparts of Fort Wagner. And I am sure

that if he did not reach the fort that night, he did not get a chance to

inspect it for three long months.

Now, on our charge we came to

the slope that he speaks of and descended into the ditch. We crossed the ditch

and ascended the upward slope and our men did actually reach the parapets of

Wagner and were killed on the parapets and fell inside the fort when killed as

did Colonel Shaw of which there is abundant proof, by both Federals and

Confederates. I crossed the ditch with the flag and ascended the rising slope

which was of sand until I came so near the top that I could reach it with my flag,

and at this time the shot, grape, canister, and hand grenades, came in showers

and the columns were leveled. I found myself the only man struggling and at

this instant I halted on the slope, still holding the flag erect in my hand.

In this position I remained

quite a while, thinking that there were more to come, and that we had captured

the fort. While in this position, I saw a company coming toward me on the

ramparts of the fort and I thought they were Federal troops and raised my flag

and shouted to them at the top of my voice, but before they saw me, I

discovered by the light of a discharged cannon their flag to be that of the

Confederates. Judge for yourselves how close I must have been to them on that

dark night. But they did not see me, and I rolled my flag around the staff,

remaining still in the position that I had held for quite a while and finding

myself to be the only struggling man, as all around me, under me, and beside me

were dead or dying and wounded. This was after the retreat for I did not hear

the order to retreat.

I thought then I would try to

get away as I saw no one standing erect but myself. I descended the slope in

the ditch over the dead and dying, and the ditch that was dry half an hour

before when I crossed it now comes up to my waist in water; but by the help of

the Good Father, I struggled and crossed the ditch and crawled up the slope on

my return. I still held the flag in my hand and reached the top of the slope

going back. I had not been shot until I reached the place where I received a

bullet in the left hip. I was not prostrated but continuing struggling to the

rear, seeing no living man but myself moving.

When a little farther on, I was

challenged by someone and upon answering he proved to be a man of the 100th

New York. This man came to me. The sergeant speaks of the words spoken that

night; I said many things that night that have never been printed, of them this.

“Are you wounded?” I was asked and told him I was. “What flag is that you carry?”

I told him the flag of the 54th Massachusetts. He said, “I am not

wounded. I will help you down the beach.” He came to me and got on my wounded

side and took me by the arm and said, “Let me carry the flag, you are pretty

badly wounded.” I told him I would not give that flag to any living man save a

member of the 54th Massachusetts.

So, on we went until we reached

the rear guard where we were halted and examined. The officer examined and

found me wounded, and the other man he sent back to his regiment. The officer

asked my number and regiment and passed me over to the Ambulance Corps with instructions

to find my regiment which was done.

As I reached the remnant of my

regiment, I tried to hurrah, in fact I did hurrah, and the boys hurrahed for

the flag that had been brought back to them and the man that brought it. I said

to them, “Let us go back to the fort.” And the officer in charge [Captain Luis

Emilio] said “Sergeant, you have done enough. You are badly wounded, you had

better keep quiet” or words to that effect when I replied, “I have only done my

duty; the old flag never touched the ground.” It did not to the best of my

knowledge while I had it, although I was struck twice after that.

This was on Saturday night

probably at midnight on Morris Island and I lost myself; did not regain consciousness

until Monday afternoon when I had been carried to the hospital at Beaufort,

South Carolina. Now regarding the medal. I received a medal and if I had time,

I would describe it fully. But suffice it to say this medal was lost at one

time and found in the city of Boston, and when I went to obtain it, I carried it

to a jeweler and had a patent fastener put on it. The deed I performed, the

medal I have, and though it was but lead, I prize it as a diamond.

Source:

Account of Sergeant William H. Carney, Co. C, 54th

Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, National Tribune, January 5, 1893, pg.

4

Comments

Post a Comment