Following Glory: Two New Yorkers Recall the Charge on Battery Wagner

Much historical attention has been focused on the efforts of the 54th Massachusetts in being the initial regiment of the assault upon Battery Wagner on July 18, 1863; however, today’s post dives into the story of the Federal regiments that followed the 54th in the assault column. A total of two brigades took part in the assault- the leading brigade under General George C. Strong was led by the 54th Massachusetts, followed by the 6th Connecticut, then the 48th New York, all of which managed to climb the ramparts, but the remainder of Strong’s brigade (the 9th Maine, 3rd New Hampshire, and 76th Pennsylvania) became pinned down by Confederate artillery fire and did not get into the fort.

The ‘second wave’

of the assault column was Colonel Haldimand Putnam’s four-regiment brigade consisting of his own 7th New Hampshire, the 100th

New York, and two Buckeye regiments, the 62nd Ohio and 67th Ohio both of whose stories at Battery Wagner have been previously covered on the

blog. Putnam’s men had no better success than General Strong’s men

and suffered heavy casualties trying to push the assault over the hump. Shortly

after midnight, the exhausted Federals fell back leaving hundreds of their dead

and wounded strewn along the ramparts.

Today’s post will feature accounts from a pair of New Yorkers who took part in the ill-fated assault: William W. Watkins of the 48th New York and William H. Mason on Co. C of the 100th New York. Watkins, wounded and captured during the assault, called it simply “a short work of death.” Both letters originally saw publication in New York state newspapers and appear courtesy of the New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center.

Private William W. Watkins, Co. B, 48th New York:

This morning,

the 48th New York came into camp, wet through, and completely used

up after all these days and nights of excitement and hard work. They had one

ration of whiskey and received a few hours sleep when the regiment was ordered

to move to the front in line of battle. The batteries and naval ships had

already opened fire and were directing their fire on Fort Wagner when suddenly

Fort Sumter and other well-known Rebel strongholds were all speaking by the

cannon’s loud voice.

It was a grand

sight for us to witness. About 5 or 6 p.m., we received a ration of whiskey

having had but little to eat during the day; all around us as far as we could

see was one swarm of shells flying and exploding. As evening grew near, the sea

breeze fanned us a little then we started double quick up the beach for Fort

Wagner. Cheers were given to the 48th by other regiments, General

Strong riding along without hat or cap, noticing us as if it might be for the

last time, but it was a brave and honest expression of hope for victory. We

heartily cheered the general and on we went, under severe shelling from Sumter

from which place we could be seen and our motive understood.

When within a

few yards of Fort Wagner, volley followed volley, and the Minie balls took down

our men while in turned we aimed at the heads of the Secesh. A steady battle was

not on the work, the shades of night overtook us and the fight grew more

desperate. Our men fell but gained steadily, crossing the moat and over the

first ditch, and on to the parapet with our colors. Colonel Barton was wounded;

Lieutenant Colonel James Green of Troy, N.Y. was killed while driving his knife into

a Secesh gunner. General Strong was wounded, too, but on they came to the slaughter.

|

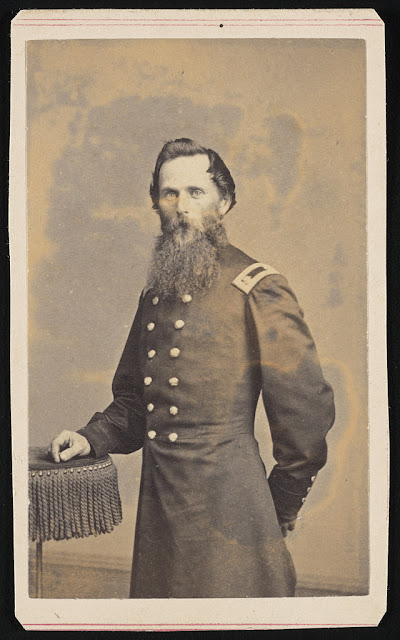

| Lieutenant (later major) James A. Barrett Co. H, 48th, N.Y. Wounded at Fort Wagner |

Our men are in

close action and two bayonets were run through a Rebel colonel who boldly came

out in the night endeavoring to rally his men “to glory” as he remarked.

Private Burnett of Co. K took the Rebel’s sword and brought it from the

battleground. Now came the tug of war. The 9th Maine played on us

the same trick they had previously done on the same ground with the 76th

Pennsylvania; it seems hard to go back on any regiment that has anything to do

in this war, but so very important to us was the capture of Fort Wagner that

any regiment which failed to support the storming party already grasping the

prize should receive the worst of censure.

We found the

fort was arched with caves and holes in the earth, entrenchments and ditches

all filled with the enemy waiting for us. There were sand heaps of great

thickness, palmetto logs, cotton bales, iron, and being regularly casemated it will

take much naval power to reduce it.

Our men were

being taken prisoners and we in turn took some Rebels prisoners. It was a

hand-to-hand fight. I was taken prisoner but escaped the same night. On my way

back to our lines, a shell from Sumter exploded within two or three feet of my

face and from that instant I have not been able to write until today (July 29th).

I didn’t know anything until the next day at about 11 o’clock when I was

brought off the battlefield by two privates of another regiment who, in the

excitement of the hour, took me to be a Rebel.

The 100th

New York, by some mistake, fired into our regiment and did much injury to the

48th. Glass bottles, nails, hand grenades, buckshot, and small

pigeon shot were used against us; and it can be proved that chain shot was used

as a piece was brought off by our men. It was a short work of death. But few of

the old 48th volunteers are now left. But the Rebels say the 48th

did not fight like men but like tigers and also that no short contest since the

war started has equaled the desperate charge on the night of the 18th

at Fort Wagner.

Could the regiments but have had light to see and work harmoniously, the fort would have been ours but as strong a place as it is, and dark as it was that night, it is no wonder that large a number were killed and wounded.

Private William H. Mason, Co. C, 100th New York:

On July 18th

at daylight, we fell back from the picket line to the rifle pits. The Rebs

commenced shelling us as soon as they could see to which our gunboats answered

rapidly. Around the middle of the forenoon, our batteries opened and the ironclads

commenced moving up and at 11:55 the first shot was fired from the iron fleet,

the wooden blockaders keeping up a smart fire at long range. Moultrie kept almost perfect silence during

the day. The bombardment continued from land and water until about 5 o’clock

when it appeared that the fort had been silenced.

The columns then

commenced moving to take it by storm. Fort Sumter shelled our troops as they

advanced until we got to within close range of Fort Wagner then the Rebs poured

in a murderous fire of grape, canister, and musketry, besides throwing hand

grenades. Regiment after regiment charged on the fort, each one retreating in

good order in their turn except the 9th Maine which broke and ran in

a confused mass through the lines of the 6th Connecticut, 7th

New Hampshire, and the 100th New York. The 54th

Massachusetts led the charge and did well with the exception of a few

panic-stricken men.

Not more than

half of any regiment in the charge came out unhurt. We had almost 4,000 men in

the field with no artillery against 1,500 men behind breastworks, pits, and

bomb-proofs. It was dark when the fight commenced and it lasted about three

hours. Our retreating, battle-worn, and wounded troops were fired into and cut

down by our own drunken artillerymen of the 1st U.S. and 5th

Rhode Island who answered the groans of the wounded with “Go to the front you

cowardly dogs, or we will blow your brains out!”

Our regiment went in with 15 officers and 509 enlisted men; the next morning the assembly was beat to ascertain our loss. All we could muster was five officers and 225 men.

Letter from Private William W. Watkins, Co. B, 48th New York, Brooklyn City News (New York), August 1863

Letter from Private William H. Mason, Co. C, 100th

New York Volunteer Infantry, Buffalo Morning Express (New York), July

29, 1863, pg. 2

Comments

Post a Comment