Fredericksburg on the Other Leg: A Blue and Gray View of Pickett's Charge Part II

Pickett's Charge has been traditionally presented as the high point of Confederate fortunes in the East; as a matter of fact, a monument denoting the High Water Mark of the Confederacy is located at the Copse of Trees to mark the furthest penetration of Union lines during the ill-fated attack of July 3, 1863. In this two-part series, we'll examine accounts from two officers who participated in the action: one who wore the blue, and one who wore the gray.

In the second part of the series, we'll examine the reminiscences of Captain Henry Thewat Owen who served in Co. C of the 18th Virginia. The 18th Virginia served in General Richard Garnett's all-Virginia brigade of General Pickett's division and anyone familiar with the film Gettysburg and it's depiction of Pickett's Charge will instantly recognize much of Captain Owen's story.

18th Virginia Infantry, Garnett’s

Brigade, Pickett’s Division, First Corps (Longstreet)

Our artillery

was stationed along the crest of Oak Ridge and Seminary Ridge, composed of

about 120 cannons, and stretching along the brow of these ridges for a mile.

The supporting detachments were placed about a hundred yards in the rear of

this line of batteries and lay down in the tall grass with a cloudless sky and

a bright July sun pouring its scorching rays almost vertically upon us. We listened

and watched in painful suspense for some sound or movement to break that

profound stillness which rested over the vast battlefield and depressed the

spirits like a dreadful nightmare.

At 1 o’clock

this awful stillness was suddenly broken and the men startled by the discharge

of a couple of signal guns fired in quick succession, followed by the silence

of half a minute, and then while their echo was yet rolling along the distant

defiles, an uproar began as wonderful as had been the previous silence. Our

guns opened at once with a crash and thundering sound that shook the hills for miles

from crest to base. They were instantly replied to by about 80 guns along the

front of Cemetery Ridge about a mile in front.

The air was

filled with clouds of dust and volumes of sulfurous, suffocating smoke which

rolled up white and bluish gray and hung like a pall over the field. No sound

ever equaled the tremendous uproar, the ceaseless din of thousands of shrieking

shots and shells falling thick and fast on every side and bursting with

tremendous explosions.

After two

hours, the firing suddenly ceased and silence again rested for half an hour

over the battlefield during which time we were rapidly forming our attacking

column just below the brow of Seminary Ridge. Long double lines of infantry

came pouring out to the woods and bottoms, across ravines and little valleys,

hurrying on to the positions assigned them in the column. Two separate lines of

double ranks were formed a hundred yards apart and in the center of the column

was placed General Pickett’s division, nearly 4,400 privates, 244 company

officers, 32 field officers, and four general officers, making 4,761 all told.

In the first line was placed Kemper’s and Garnett’s brigades side by side, covered

by Armistead’s brigade in the second line.

Riding out in

front, General Pickett gave a brief, animated address to the troops and closed

by saying to his own division, “Charge the enemy, and remember old Virginia!”

Then came the command in a strong clear voice, “Forward! Guide center! March!”

The column, with a front of more than half a mile, moved up the slope. Meade’s

guns opened upon us as they appeared above the crest of the ridge but we

neither paused nor faltered. Round shots, bounding along the plain, tore

through our ranks and ricocheted around them. Shells exploded incessantly in

blinding, dazzling flashes before, behind, overhead, and among us. Frightful gaps

were made from center to flank, yet on swept the column and as it advanced, the

men steadily closed up the wide rents made at every discharge of the batteries

in front.

A long line of

skirmishers, prostrate in the fall grass, fired at the column as it came into

view, rose up within 50 yards, fired another volley into its front, then trotted

on before it, turning and firing back as fast as they could reload. The column

moved on at a quick step with shouldered arms, and the fire of the skirmish

line was not returned. Halfway over the field an order ran down the line, “Left

oblique.” We promptly obeyed and the direction was changed 45 degrees from the

front to the left. Men looking off toward the left flank saw that the

supporting columns there were crumbling and melting rapidly away.

The command now came long the lines, “Front, forward!” and the columns resumed its direction straight down the center of the enemy’s position. Some men, now looking to the right, saw that the troops there had entirely disappeared, but how or when they left was not known. Guns hitherto employed in firing at the troops on the right and left sent a shower of shells after the fleeing fugitives and then trained upon the center where the storm burst with ten-fold fury as the converging batteries sent a concentrated fire of shots and shells into the column.

The destruction

of life in the ranks of that advancing hose was fearful beyond precedent,

officers going down terribly mangled, but Garnett still towered unhurt and rode

up and down the front line saying in a strong calm voice, “Faster men! Faster!

Close up and step out faster, but don’t double quick!” The column was

approaching the Emmitsburg road where a line of infantry, stationed behind a

stone fence, was pouring in a heavy fire of musketry. A scattering fire was opened

along the front of the division upon this line when Garnett galloped along the

line, calling out “Cease firing!” His command was promptly obeyed, showing the

wonderful discipline of the men who reloaded their guns, shouldered their arms,

and kept on without slackening their pace which was still a quick step.

The stone

fence was carried without a struggle, the infantry and the skirmish line swept

away before the division like trash before the broom. Two-thirds of the distance

was behind and the 100 cannons in the rear were dumb and did not reply to the

hotly worked guns in our front. We were now 400 yards from the foot of Cemetery

Hill when away off to the right, nearly half a mile, there appeared in the open

field a line of men at right angles with our own- a long, dark mass dressed in

blue and coming down at a double quick upon the unprotected right flank of

Pickett’s men. They marched with their muskets upon the right shoulder shift,

their battle flags dancing and fluttering in the breeze, their burnished

bayonets glistening above their heads.

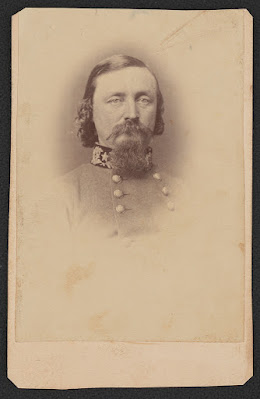

|

| This fine print from Don Troiani depicts General Richard Garnett leading his brigade towards The Angle with the 18th Virginia at left leading the charge. (Don Troiani) |

Garnett galloped

along the line saying, “Faster men, faster!” but when the front line broke

forward into a double quick when Garnett called out, “Steady men, steady! Don’t

double quick. Save your wind and ammunition for the final charge!” Then he went

down among the dead and his clarion voice was heard no more above the roar of

battle. The enemy was now seen strengthening his lines where the blow was

expected to strike by hurrying up reserves from the right and left. The

distance had again shortened and officers in the enemy’s lines could be

distinguished by their uniforms from the privates. Then was heard behind that

heavy thud a muffled tread of armed men, that roar and rush of tramping feet,

as Armistead’s column from the rear closed up behind the front line. Armistead,

taking command, stepped out in front with his hat uprighted on the point of his

sword and led the division, now four ranks deep, rapidly, and grandly across

the valley of death.

Then again,

the sound of grape and canister filling the air. The column broke forward into

a double quick and rushed toward the stone wall where 40 cannons were belching

forth grape and canister twice and thrice a minute. A hundred yards from the stonewall,

a flanking party on the right halted suddenly within 50 yards and poured a

deadly storm of musket balls into our line, and under this terrible crossfire

the men reeled and staggered between falling comrades, the right coming in

pressing upon the center and crowding the companies into confusion. But all

knew the purpose to carry the heights in front and the mingled mass from 15 to

30 men deep, rushed toward the stonewall while a few hundred men without orders

faced to the right and engaged the flanking party. Muskets were seen crossed as

some men fired to the right and others to the front and the fighting was

terrific, far beyond the experience of our men who for once raised no cheer

when the welkin rang around them with the Union huzzah. The old veterans saw

the fearful odds against them and other hosts gathering darker and deeper

still.

Time was too

precious and too serious for a cheer. The men buckled down to the heavy task in

silence and fought with a feeling like despair. The enemy were falling back in

front while officers were seen among their breaking lines striving to maintain

their ground. We were within a few feet of the stonewall when the artillery

delivered their last fire from guns shotted to the muzzle. A blaze 50 feet long

went through the charging, surging host with the gaping rent to the rear, but

the survivors mounted the wall, then over and onward rushed up the hill close

after the gunners who waved their rammers and sent up cheer after cheer as they

felt admiration for the gallant charge.

On swept the

column over ground covered with the dead and dying men where the earth seemed

to be on fire, the smoke dense, and suffocating, then sun shut out, flames

blazing on every side, where friend could hardly be distinguished from foe. Pickett’s

division, in the form of an inverted V with the point flattened, pushed forward

fighting, falling, and melting away till halfway up the gill they were met by a

powerful body of fresh troops charging down upon them. This remnant of about a

thousand men was hurled back out into the clover field. Armistead was down

among the enemy’s guns mortally wounded and was last seen leaning upon one

elbow, slashing at the gunners to prevent them from firing at his retreating

men.

|

| General George Pickett |

Out in front

of the breastworks, the men showed a disposition to reform for another charge,

and an officer looking at the frowning heights with blood trickling down the

side of his face inquired of another, “What shall we do?” The answer was “if we

get reinforcements soon, we can take that hill yet.” But no reinforcements

came, none were in sight, and about a thousand men fled to the rear over dead

and wounded, mangled and groaning dying men scattered thick far and wide while

shot and shell tore up the earth and Minie balls flew around them.

At a ravine a

few hundred yards behind the Confederate batteries, the fugitives passed through

a narrow pass without distinction of rank, pushing, pouring, and rushing in a

continuous stream, throwing away guns, blankets, and haversacks, as they

hurried on in confusion toward the rear. An effort was made to rally the broken

troops and all sorts of appeals and threats were made to the officers and men,

but they turned a deaf ear and hurried on, some of the officers even jerking

loose with an oath from the hand laid on their shoulders to attract attention.

At last, a few privates hearkened to the appeals and halted, forming a nucleus

around which about 30 others soon rallied and with these a picket was formed

across the road as a barrier to retreat and this stream of stragglers dammed up

several hundred strong.

General

Pickett came down from the direction of the battlefield weeping bitterly and

said to the officers commanding the pickets, “Don’t stop any of my men. Tell

them to come to the camp we occupied last night,” and passed on himself alone

to the rear. Other officers passed by, but the picket was retained at this

point until Major Charles Marshall (Lee’s staff) came galloping up from the

rear and inquired, “What is this guard and who placed it here?” Finding the

officer without orders, he moved the picket back a few hundred yards and

extended the line along the stream found there. Here the guards did duty until

sundown, arresting all stragglers from the battlefield. Colonel Marshall took them

back to General Lee.

Source:

“General Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg,” Captain Henry

Thweatt Owen, Co. C, 18th Virginia Infantry. Joel, Joseph A., and

Lewis R. Stegman. Rifle Shots and Bugle Notes, or the National Military

Album. New York: Grand Army Gazette Publishing Co., 1884, pgs. 350-354

Comments

Post a Comment