Gunned Down at Guntown

I am proud to present the Brice’s Crossroads campaign diary

of First Lieutenant Thomas A. Carter of Co. E of the 20th Tennessee

Cavalry. Lieutenant Carter’s diary appeared in serial form from March 10-15,

1935, in the pages of the Paris News of Paris, Texas. A.W. Neville wrote

that the diary was copied from “an old scrapbook owned in Detroit [Texas] and

covers several months of his life in service from 1863-1864 east of the

Mississippi River. The diary was kept in a small pocket memorandum book.”

It took some digging

to determine the author of this diary; the newspaper articles in which it

appeared mentioned the soldier as being Lieutenant Carter. The first diary

entry mentions his enlistment in Captain W.D. Hallum’s company of the 15th

Tennessee Cavalry on September 17, 1863, at Paris, Henry Co., Tennessee, but I

could find neither Captain Hallum nor a Lieutenant Carter in the 15th

Tennessee. Additionally, the 15th Tennessee didn’t fight at Brice’s

Crossroads and his diary clearly describes his wounding in that fight. I

eventually found Captain W.D. Hallum as commanding Co. E of the 20th

Tennessee Cavalry (Russell’s) and this proved the match. On the rolls of the which

I found a First Lieutenant T.A. Carter; a search of Find-A-Grave led to Thomas

Alexander Carter who was indeed the author of this diary.

Thomas was

born November 19, 1834, in Henry County, Tennessee to John Calvin Carter and

his wife Mary Ann Dinwiddie Carter. The family moved to Texas in 1843 but by

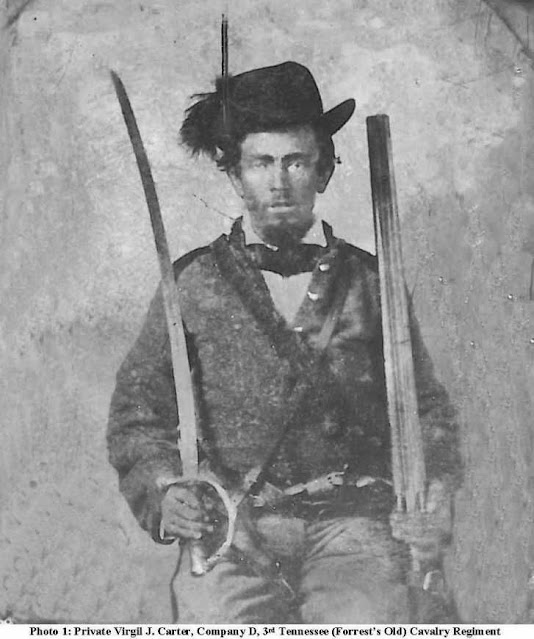

1860 Thomas was back in Tennessee. Both Thomas’ father and his younger brother

Virgil (pictured below) served in the Confederate Army; as a matter of fact,

Virgil served in Nathan Bedford Forrest’s 3rd Tennessee Cavalry,

enlisting in October 1861.

As noted in

the history of the 20th Tennessee, Thomas Carter enlisted in Hallum’s

company as noted above, bringing a sorrel horse valued at $1,000 into the army

with him. He was elected first lieutenant of the company on October 19, 1863. “I

ran against Bill Foust and was elected first lieutenant; received commission and

entered on duty. We have 71 men in our company,” he wrote in his diary.

Lieutenant Carter was wounded at Brice’s Crossroads as he describes below and sent to the hospital; eventually he was captured by the Federals and spent the rest of the war as a prisoner. He survived the experience and after the war moved to Texas, later being elected mayor of Clarksville, Texas. He died June 16, 1891, at the age of 56 and is buried at Clarksville Cemetery.

June 1, 1864: Preparations were made and General Forrest with

most of the command went or started for Alabama. General Tyree H. Bell, our

brigade commander went with him. Colonel Robert M. Russell, being the senior

officer, was left in command of the brigade with captain Hallum in command of

the regiment and the writer in command of our company.

June 3, 1864: I was ordered to take the company horses and go

to Pontotoc and have them shod.

June 5, 1864: Arrived at Pontotoc and put the blacksmith to work. About midnight a courier arrived with orders directing me to gather every available man and scout in the direction Ripley as the enemy was moving on our reserve. I took 16 men and sent the rest back to camp at Tupelo. Commenced raining and we had a hard time. Bought a pair of rawhide boots at the moderate price of $150 cash and glad to get them at that. Sergeant Joe Palmer’s horse was taken sick and he had to go back after several days.

June 9, 1864: While near Ripley an old man came running out

to the road making a great many signs and when I inquired what the matter was,

he said the town for full of Federal troops and the picket was only a few hundred

yards from his house and we would all be captured directly. I halted the squad

and advanced a short distance off to the right with the intention of getting nearer,

if possible, without being discovered. We crossed through a skirt of woods and

were nearing the main road from Rienzi when the rattle of sabers and the thud of

horses’ feet met our ears, apparently only a few yards distant.

Captured was my first thought. Right about march was the order that came from the commander. Halt! Right into line, march was my order for I could not think of retreating until we knew something more. Just at this moment one of our boys sang out, “They are our own men, lieutenant.” Sure enough, it was the advance guard of our own command. Lieutenant Armstrong was commanding and we laughed over our mutual surprise for he thought we were the Yankees and vice versa. We then joined our squads and went on to Ripley but the Yankees had passed through the night before. I received orders then to rejoin the regiment and you may be sure we were all glad to be relieved. But the worst was yet to come.

The Brice's Crossroads monument.

June 10, 1864: On this morning General Forrest, with the forces he had started to Alabama, returned and we engaged the federals near Guntown on Tishomingo Creek and fought all day. The Yankees had about 9,000 men including Negro infantry and cavalry. Our men were what is called mounted infantry, taught to fight either on foot or horseback as occasion might require. About the middle of the morning, the writer fell badly wounded in the back of the neck and right shoulder.

After I fell, the first thought was that we were whipped and that the Negro troops would mutilate my body as we had understood that they had sworn to show Forrest and his men no quarter. I saw our men retreating but I could not get up. Oh, what a horrible feeling! I cannot describe it.

To my surprise, however, the enemy did not advance. In a few moments our own boys were around me again and the kind voice of Captain Hallum greeted me with “Hello, Carter, are you badly wounded?” I replied that I did not know how bad for I had no feelings, perfectly dead except a slight tingling sensation like a foot asleep. He ordered John Smith to assist me to the rear; Dave Young volunteered his services to assist me and let John, brave boy that he was, go into the fight and from all accounts many poor Feds were made to bite the dust by that boy.

After an hour of walking and stopping to rest under the continuous volleys of musketry and grapeshot, my friend Young succeeded in getting me to the field hospital. I was almost famished for water. What I saw during the rest of the evening is too sickening to describe, even if my pen was able. Two ladies, God bless them, whose residences were appropriated as the hospitals and they waited upon the wounded and dying with heroic devotion. The houses were full, the passages full, and they were lying over the road.

In about two hours, I suppose, my own captain was brought in

with a pistol ball in his arm, very painful though not dangerous. Shortly

afterwards John Hurt came in, also wounded in the arm, The place was so crowded

that Captain Hallum decided to try and find a better place for me and himself.

He was able to ride and with his arm dressed and, in a sling, he struck out for

better accommodation which he found about a mile away at the residence of a Mr.

Bryson.

Source:

Diary of First Lieutenant Thomas Alexander Carter, Co. E, 20th

Tennessee Cavalry, Paris News (Texas), March 14, 1935, pg. 6; March 15,

1935, pg. 4

Comments

Post a Comment