Salvation Close at Hand: Federal POWs Exchanged at Wilmington

Captured on the second day of the Battle of Chickamauga,

Sergeant Samuel S. Boggs of the 21st Illinois had survived 18 months

imprisonment in some of the worst camps throughout the South: Libby, Belle

Isle, Danville, Andersonville, and now at Florence, South Carolina. Attached to

the hospital squad, he remained at Florence when many of the haggard survivors

moved off to another camp at Goldsborough.

“We of the

hospital squad stayed with the sick and gathered from in the prison all the

sick we could put under our sheds and arranged the balance so we could give

them water,” he wrote. “They were decreasing rapidly by death. The Rebels told

us if we would take an oath not to go beyond the stockade, they would take off

the guards. We consented, glad to get rid of those murderers and then swore not

to hold conversation with the Negroes or slaves and not go beyond the limits of

the stockade. The nurses counseled together and agreed to stay with the sick as

it would not be long until our troops would release us.”

Boggs was right as within a few days;

he would find himself back in Union lines. His account of deliverance comes

from his 1887 book Eighteen Months a Prisoner Under the Rebel Flag which

is reproduced below.

One morning

about the last of February, a Rebel officer came in and ordered us to get every

man over to the railroad about a quarter of a mile away and they would take us

to our lines. Some of the sick were taken in wagons, some crawled most of the

distance. We took all but those thought to be dying; those were left without

help of any kind and there were perhaps 30-40 men in this condition. We finally

loaded the sick in freight cars and started running all that day and night, and

about the middle of the second day our train stopped in the rear of a Rebel line

of battle.

The Rebels

were all excitement and soon ran our train back as fast as it could go. We

would have jumped and taken to the woods if it hadn’t been for our sick boys.

In time, the train stopped and we were ordered off the cars and camped in the

woods; this was a picnic for us, but the Rebels acted like they expected an

attack. Some Rebel cavalry helped them guard us that night and the next day we

were sent back to our old quarters at Florence. This discouraged our sick, but

we cheered them up and told them that the “salvation of the Lord was close at

hand and the Confederacy was bursted.”

We found some

of those who were dying when we left still alive four days later. We wet their

lips with water and fixed them as comfortably as we could. Some whom we took with

us died and we left them near the railroad for the section men to bury. About

the 1st of March we were ordered to the road again and worked our

sick aboard the cars and started over the same road. We knew now that our forces

had captured Wilmington. We ran along without adventure. Sometimes when the

train would make a short stop, we would take out our dead and lay them beside

the tracks.

We were going

in the direction of Wilmington, our engine flying a white flag. We were in suspense

to know what was going to be done with us. After awhile some of the boys said, “Hello,

there’s a blue coat!” We looked and sure enough, there were several blue coats

out foraging. Peeping out the door, we saw bright guns flashing in the sunlight

and soon made out that it was a line of Union pickets.

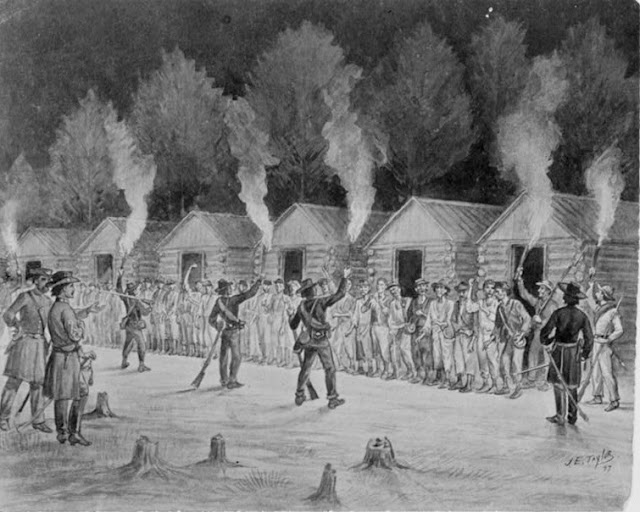

The sick men

crawled to the door and looked out. Our guards offered no objection but looked

badly scared. Our train moves up with the engine through the line of pickets.

The Rebel officer in charge of us salutes a Union major. They talk a moment and

the major signals a Union officer at the picket line who advances with about 30

unarmed men and several surgeons. The Rebel guards now moved a few yards away

and looked ashamed and sneaking. There is not a word exchanged between them and

our men; our Union friends now come up to the cars and kindly help the sick

out. These Union soldiers helping are wiping their eyes; others are setting

their teeth hard and casting wicked glances at the Rebels, but there is a flag

of truce that must be respected and they cannot express their thoughts.

A Union

soldier comes up and asks if there is a man with us by the name of Wilcox. A

sick man recognizes the speaker and says, “That’s your brother,” pointing to

one of the unfortunates whose mind is gone. He does not know his own name when

called by his brother. All this does not affect us; we have seen nothing but

misery for a year and a half and it seems strange to see people weep when we

are so full of joy. We try to sing “Home at last from a foreign shore,” but the

voices are weak and break down.

“The condition of these prisoners as they arrived here as they are now is beyond the power of the English language to describe. All the descriptions of the barbarous and inhuman treatment these poor fellows have suffered, the misery, pain, and privations they have endured, are but the faint glimmering of the reality as they presented themselves to our view at this place. When they were landed here from the cars, a large number of them were unable to walk to the pen or prison and fell down by the way, or were left on the ground when they were unloaded from the cars. Reduced as many of them were to mere skeletons, a living mass of filth, disease, and vermin, suffering the last agonies of death by starvation, lying nearly naked in the streets and by the waysides as well as in the pen they were driven to.” ~ Surgeon Lyman A. Brewer, 111th Ohio

We went

through the line of guards to the edge of the woods where the kind soldiers

built up big fires and did everything in their power to make us comfortable.

They divided their clothing, giving us shirts, stockings, everything they could

possibly spare. Wilmington was more than a mile away and these troops on picket

were part of General John Schofield’s 23rd Army Corps. Theye were as

noble-hearted and fine-looking soldiers as I ever saw. Our forces had been in

possession of Wilmington but a short time and they were not prepared to receive

in clothe us.

Some wagons

came over from Wilmington loaded with rations. Camp kettles were put on the

fire and coffee made, boxes burst open, and crackers given out along with

vinegar and onions, all of which many of us hadn’t tasted for 18 months. Our

surgeons looked after those who did not seem to have judgment and warned them

not to eat too much; they said we could drink all the coffee we wanted and some

drank until they seemed intoxicated. The surgeons took charge of the sick whose

numbers were being rapidly reduced by death.

Next morning, we got some soap from the soldiers and a number of us went to a little creek nearby and washed off as much prison filth as we could scour loose. We ate a hearty breakfast and all who were able to walk marched over to Wilmington, our boys yelling themselves hoarse when we sighted the old stars and stripes floating from a steeple over in Wilmington. We felt that we were in God’s country at last. It seemed as if we had been gone from it for 20 years or more and it seems now, looking back, that it cannot be possible that we did pass through those awful hells.

Eventually, about 9,000 Union soldiers were exchanged at Burgaw Station near Wilmington in the first week of March 1865.

Sources:

Boggs, Samuel S. Eighteen Months a Prisoner Under the Rebel Flag. Lovington: S.S. Boggs, 1887, pgs. 55-58

Letter from Surgeon Lyman A. Brewer, 111th Ohio Volunteer

Infantry, Hillsdale Standard (Michigan), April 4, 1865, pg. 1

Comments

Post a Comment