A Buckeye Surgeon Recalls the Dark Passage Through Spring Hill

Safely in camp in Nashville, Tennessee on December 6, 1864, Surgeon William Morrow Beach of the 118th Ohio Volunteer Infantry penned this lengthy account of the Tennessee campaign through which he had just passed. The trials and dangers of the overnight march from Columbia through to Franklin still filled him with horror and relief that somehow the army had gotten through.

Dr. Beach had served as assistant surgeon with the 78th Ohio for two years, taking part in the aftermath of Shiloh, Holly Springs, and the Vicksburg campaign, later becoming a member of the Society of the Army of the Tennessee. In June of 1864, he was commissioned surgeon of the 118th Ohio and served with that regiment for a year, mustering out June 24, 1865. After the war, he returned to his farm in Madison County, Ohio and continued to practice medicine, also serving as a state senator from 1869-1873. Surgeon Beach died of paralysis May 5, 1887 and is buried at Deer Creek Township Cemetery in Lafayette, Madison Co., Ohio.

|

| 118th Ohio Letterhead |

Surgeon Morrow's letter was published in the December 22, 1864 issue of the Madison County Union and is presented in two parts. Part I covers the march from Columbia through Spring Hill, while Part II covers the Battle of Franklin and the retreat to Nashville.

Nashville, Tennessee

December 6, 1864

My brigade left Johnsonville, [Tennessee] on the morning of the 23rd ultimo. We took the cars and arrived at Nashville about dark. We did not disembark, but took the track for Columbia, 45 miles south of this city. We arrived at Columbia about three o’clock in the morning of the 24th. Leaving the cars, we marched a mile from town and took position on a hill. About 7 o’clock in the morning, we fell hastily into line and pushed out to drive away a body of cavalry that had overpowered ours and had driven them back pell-mell. Arriving upon the grounds only a mile from the town, we met the Third Division of our corps (23rd) that had marched ten miles that morning, arriving at the point of the attack just in time to check the Rebel advance and frighten them most terribly. We took position on the west side of town about a mile out. Our position was on the right and [General Jacob] Cox’s Division was on our left. Nothing of interest transpired through the day. General John Schofield was there and with Cox’s division, two brigades of my division, and an indefinite force of cavalry; we put on a decidedly military aspect. The cavalry that threatened us was Forrest’s. It was Hood’s advance.

|

| General Jacob D. Cox |

On the 25th, the 4th

Corps commenced coming in. Cox had been at Pulaski. By night on the 25th,

we had all got into position and were rapidly fortifying. Columbia is situated

on Duck River. The river runs, as a general direction, westwardly. It makes a

short bend around to the north and Columbia is built on this peninsula about a

mile from the stream. Our lines were semicircular with our right and our left

resting on the river. The position of my division was on the rocky cliffs of

Bigby Creek. Immediately in our front across the creek was the residence of

O.A.P. Nicholson, the same to whom the historical “Nicholson Letter” of General

Cass was written. He has been dead several years. About 2 o’clock on the

morning of the 26th, my brigade was quietly drawn in and thrown

across the river to guard the railroad bridge. Hood’s main infantry force had

all come up by this time and the situation was getting somewhat critical. The 4th

Corps was on the left of the 23rd Corps, and the Rebel lines were

tightening around us. Our trains were all on their way to Nashville and we were

holding Hood only to give them time to get safely out of the way. Hood was

getting more and more pugilistic. About 9 o’clock in the evening, we reached the river

again to help hold our inner line, while the whole of our outer line was

abandoned, the troops drawn in, and the 4th Corps had commenced

crossing the river. My division was the last to come over, which it did just

before daylight on the morning of the 27th.

At daylight our skirmish lines were called in and in less than an hour, the opposite bank of the river was lined with Rebel sharpshooters. They ran a 20-pound Parrott gun into one of our abandoned forts just on the opposite side of the river and succeeded in firing about a dozen rounds before we could drive them away. This was about 9 o’clock in the morning. I had been sitting reading the “Sorrows of Wertes” all the morning just to the rear of our batteries. One of my men had been wounded by a sharpshooter; and after dressing his wound, I left him with my hospital steward till I stepped over the hill for the stretcher bearers. Just after I left, the rebel battery opened and the wounded man was lying almost in their direct range. I thought it a matter of humanity, however, to bring him off if possible. Just as we were on top of the ridge, a solid shot hit the ground and bounding up it took my stretcher bearer just above the shoulders and dashed his blood and brains all over the ground. Two of his double teeth are all still sticking in the bark of a cottonwood tree where they were lodged. The shot lifted his body six or eight feet, with a thumb-worn testament in his breast pocket.

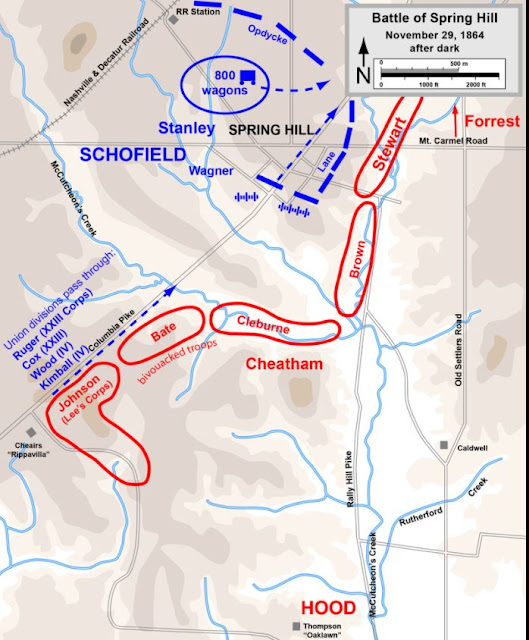

On the north side of the river, our army retained the same position as when on the south side. Skirmishing was brisk, and our artillery must have played havoc among them. About 10 o’clock on the morning of the 29th the whole army commenced falling back. We left the line of skirmishers to cover our retreat, and a small force of the 4th Corps to cover their retreat. Striking the macadamized road about six miles from the river (my division took the advance, Cox’s division followed, and then the three divisions of the 4th Corps), we arrived at Spring Hill about 9 o’clock in the evening.

|

| The situation at Spring Hill, Tennessee November 29-30, 1864 (Map courtesy of Hal Jespersen, www.cwmaps.com) |

Our cavalry and a part of the Second Division of the 4th Corps had been fighting there nearly all the afternoon and Hood’s advance of infantry had arrived two hours before us and were already going into camp only a mile from town. Two miles from town we had met their picket posts and quite a skirmish ensued in driving them away. But we did drive them away and by daylight on the morning of the 30th, our rear guard was just passing out of town. And yet within two miles of town Hood’s whole army had bivouacked for the night! We were completely flanked! We were headed off and 1,000 good troops could have destroyed our whole train and thrown the whole army into a panic. We don’t pretend to try to account for Hood’s turpitude. It is inexplicable. The only solution we can arrive at was his supposition that our main army was still at Duck Creek, or else that he expected to be astir in the morning in time to take us all in. He had crossed Duck Creek, you understand, about Columbia and had us flanked and at his mercy, only he let the golden moment slip. In the skirmish in the forepart of the night, I got lost from my brigade, so I stopped just at the limits of the town and had a cup of coffee prepared. I did not leave until 1 o’clock. The 23rd Corps was in the advance, then the long and lumbering wagon train, and the 4th Corps last. At the time I left Spring Hill, the Rebel camp looked to be two miles long. I should think there were fires enough for 40,000 troops. These were all within two miles of town and no barrier but a weak line of skirmishers.

Leaving town, I pushed rapidly along past

the wagon train. We had all the lanes and byroads leading to the pike picketed;

but there was scarcely a rod of the whole way that I did not hear the “ziz” of

the bushwhacker’s bullet. Occasionally one would get quite a volley. The

cowards would fire and then run away, when any dozen of them might easily have

cut our train and created a panic. They did succeed at one point in burning

five or six wagons and scaring the teamsters away from about a dozen more. Our

entire loss was probably 20 wagons. I arrived at Franklin just at sunrise. The

morning broke clear and bright and glorious! My heart is full on such mornings

as these. Could morning be everlasting, how faultless and pure mankind might

be! There is something in the purity and peacefulness and stillness of the

newborn day; and the still increasing crimson and gold of breaking dawn and

vanishing night shadows which is impressively suggestive of the majesty,

beauty, purity, and glory of the eternal. But enough digressing.

Comments

Post a Comment