On soil enriched with their blood: The aftermath of Gettysburg

Shortly after the conclusion of the Battle of Gettysburg, Ohio editor George G. Washburn traveled to the battlefield to render assistance to the wounded men of his local 8th Ohio Infantry. The scale of the horrors he witnessed in the coming days proved staggering.

South of the

copse of trees near the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge, he reported that “along this whole line the ground is covered

with muskets, knapsacks, clothing, broken caissons, and all the paraphernalia

of war while the stench arising from the shallow graves and dead horses utterly

baffles description,” he wrote. “An occasional farmhouse is seen riddled with

shells and deserted by its former occupants. The floors are clotted with blood

where the wounded were first borne in the heat of the action and in one chamber

I saw where a shot passed through near the floor and out on the opposite side;

the whitewashed wall was besmeared with the brains and blood of some poor soldier

who had been placed just in the range of that fatal shot.”

But the scenes of

the Valley of Death in Plum Run Valley proved too much for Washburn to endure. “So many days elapsed before

the wounded could all be picked up that when the burial corps reached the spot

the bodies of the dead we so decayed as to be immovable and there is no earth

among the rocks to cover them with.” he remembered. “Some have a few flat

stones thrown over them but most of them lay just where they fell or where they

crawled after falling. So revolting was the sight and so sickening the smell

that I retraced my steps after passing only part of the way down the ravine.”

George Washburn wrote a pair of accounts documenting the carnage of Gettysburg for his readers back in Ohio. They both ran in subsequent issues of his Elyria Independent Democrat in late July 1863.

4-1/2 miles from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

July 11, 1863

I arrived at

Gettysburg on Sunday morning at 8 o’clock and leaving my satchel at a private house,

without my breakfast for the hospital at this place on foot. I passed through

the country where the storm of shell raged with the greatest fury but as my

first purpose was to visit the wounded, it will be my first business to

describe faintly, I assure you, the horrors I have witnessed.

On entering

Gettysburg, I began to experience the effects of war in the almost sickening

effluvia which arose from the bloody field and all the way to this place the

stench was unbearable. On entering the field where the wounded of the 8th

Ohio lay, I proceeded to the tent occupied by Captain Azor Nickerson who was so

overjoyed at seeing me so unexpectedly that for some time he could not be

composed and I thought best to leave him for a time and look after others of

the 8th. Passing down the creek with Dr. Baker of Norwalk, I came to

a camp of Confederate wounded and such a sight may God in his mercy spare me

from ever witnessing again. Long before I came to the edge of the woods where

they lay, my ears were saluted with shrieks and groans such as no mortal ever

heard without melting his heart in sympathy.

Lying upon the

ground with no covering, most of them nearly naked, were 2,000 Rebels, wounded

in every part of the body, some with ghastly eyes peering upon my but cold in

death. As I passed in among them the living appealed to me in the most piteous

tones to come to their relief. One begged me to shoot him and end his misery. I

saw hundreds who had laid there a whole week wounded so severely that they were

unable to move and whom their own surgeons had entirely neglected thinking they

would soon die. Many of them were shot through the body and they were actually

rotting, huge worms crawling through the decayed flesh.

On ascending

the hill beyond, the suffering was even more terrible if possible. The men had

lain in their own filth and the heavy rain had beat upon them cooling their

fevered bodies, it is true, but covering them in all the filth that had

accumulated above and as they were unable to move, their condition was truly

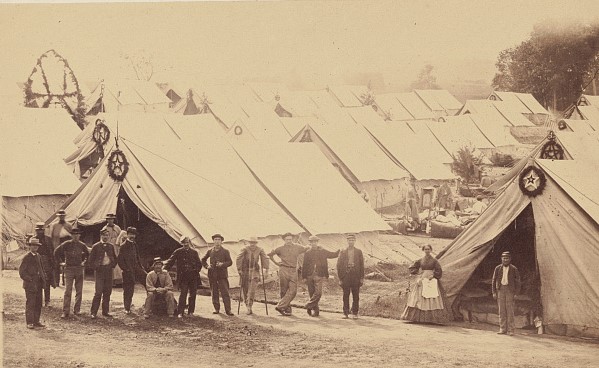

horrible. I went up to the top of the hill where our own wounded lay under

comfortable tents and were receiving every attention that could be bestowed.

Each tent contained from eight to ten men, at least one-fifth of whom had lost

an arm or a leg. They seemed to be cheerful though suffering intense pain, and

kind friends were at their sides singing and praying with those who were near

their journey’s end and ministering to their every want.

Dr. Baker and myself resolved to spend the afternoon among the Rebel wounded and being provided at medical headquarters with a supply of lint bandages and other requisites for dressing wounds, we took each a portion of the field and proceeded on our errand of mercy. The poor fellows were overjoyed at our approach and during that afternoon we relieved the pain of many a poor Rebel who, without exception, showered blessings upon us for our care and attentions.

I asked every man where he was

from and whether he was a volunteer or a conscript. A very large majority were

conscripts and freely declared their opposition to the doctrines of secession

but were forced to fight against their wishes. The officers were rabid secesh

and declared their intention to fight it out to the last. Many of the privates

said they volunteered to avoid conscription thinking they would fare better.

Just before night a heavy shower came up and I sought shelter in the large tent

where the amputating tables were placed and in the course of an hour witnessed

a large number of operations, the patients being entirely insensible from the

use of chloroform. The legs and arms, as fast as cut off, are thrown in a heap

at the side of the tent and one would think he was in a slaughterhouse at the

extent of the pile.

During my stay here, the scene

was beyond any description. The rain was pouring down in torrents, the thunder

was rolling incessantly, and from the poor Rebels on the side of the hill there

came a constant moan, distinctly heard above the noise of the raging elements,

and mingling with the chorus of many voices, singing, and praying in the

adjacent tents, no language can portray the horrors of the scene. At the same

time the surgeons were plying their knives and saw in almost unbroken silence

for scarcely a loud word was spoken while I remained in the tent. As soon as

one man was finished another was brought in on a stretcher and placed on a table,

and the other carried away to his quarters, many of them to linger a few hours

and die. May God in his infinite mercy spare me from ever again beholding such

an aggregation of human misery.

I write this on my knee by the

side of Captain Nickerson’s couch. He is sleeping under the effects of the opiates

I have administered and I fear will soon fight his last great battle. He says

he is ready to due and has every attention he needs. In the next tent are eight

Union soldiers with only eight legs; they are doing well but the moans even now

at midnight that come up from them are truly distressing. Just in front, lying

under a shelter of canvas is a Rebel officer near his end. He told me he was a

tutor in one of the law colleges in North Carolina and is certainly a man of

ability. But here he lies, shot through the lungs, so hopeless that few have

noticed him and in a few hours he will pass away.

I cannot write more tonight. You may think this picture imaginary but I assure you that no pen can portray the horrors I have witnessed. It must be seen to be appreciated. I arrived just in time to witness the most horrible part of war’s terrible results. When first wounded, men suffer no pain. It is when they become putrid with decay and when death calls them hence that the most misery is endured. I will give an account of the scene presented on the battlefield in my next.

Second Corps hospital, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

July 18, 1863

In my last

letter I promised to describe the appearance of the battlefield but after

passing over nearly every portion where the hostile armies fought, I shrink

from the task of attempting to describe it in detail.

The field

remains just as it was when the morning sun on the glorious Fourth dawned upon

the scene except that the wounded have been removed to the various hospitals on

distant fields and the dead have been mostly buried on the soil they have

enriched with their blood. The area devastated by the tread of the two armies

is about ten miles square or 100 square miles. Within this area, only a small

portion of the outer circle escaped the most complete devastation. Hundreds of

fields are seen on which it is impossible to tell what kind of crop was growing

only a few days ago. Many of the fields were enclosed with stone walls but they

have been thrown down to facilitate the march or removed to more commanding

localities to form breastworks for infantry.

Gettysburg

which in all coming time will be visited as a place of historic interest

contains about 3,500 inhabitants and is situated on the south side of the

valley, extending up the slope of the ridge which formed Meade’s line of battle

and of which Cemetery Hill is the center. I did not see a house or fence in the

southwestern part of town that was not perforated with bullets. The fighting

here was mostly done on the first day of July and nearly all the streets bear

marks of the conflict. The citizens remained in their cellars and only one was

killed, a young lady who was shot through the heart [Jennie Wade] and a few

were slightly wounded.

The once

beautiful cemetery which contains many elegant monuments is now a picture of

desolation. It was here that a portion of our batteries were placed and against

them the Rebels directed their heaviest fire from the ridge they occupied

across the valley. Shells lay scattered around amid the broken tombstones and

iron enclosures, shade trees are torn down, and fragments of caissons and

broken wheels show how fearful was the iron hail hurled against our veteran

troops.

From the

cemetery, I followed the line of breastworks to the left a third of a mile to

the spot where Ricketts’ battery made such terrible havoc in the Rebel ranks

when they attempted to break through the center. It was a little to the right

and nearly in front of this battery that the glorious 8th Ohio met

the Rebel legions and won a name that will ever remain imperishable in the

history of this war. On this spot 104 of the 207 men were killed or wounded but

they flinched not a hair amid the leaden hail. The small grove of oaks in which

Ricketts’ battery was placed is literally shelled to splinters. I counted 13

spots on one tree where cannon balls had struck, some of passed entirely

through the center a distance of 20 inches and one tree two feet in diameter by

actual measure was pierced through twice and the tree was still standing. I counted

35 dead horses within a few yards of where the battery stood and the long rows

of graves nearby show what numbers fell defending these guns when the enemy

attempted to capture them.

On the left of

this battery, the line of battle extends along a ridge of cultivated fields for

nearly two miles. Three lines of breastworks extended nearly the whole distance

with every commanding point occupied by a battery. Along this whole line the

ground is covered with muskets, knapsacks, clothing, broken caissons, and all

the paraphernalia of war while the stench arising from the shallow graves and

dead horses utterly baffles description. An occasional farmhouse is seen

riddled with shells and deserted by its former occupants. The floors are

clotted with blood where the wounded were first borne in the heat of the action

and in one chamber I saw where a shot passed through near the floor and out on

the opposite side; the whitewashed wall was besmeared with the brains and blood

of some poor soldier who had been placed just in the range of that fatal shot.

This range of

hills is connected on the left with a rocky elevation which was covered with

our batteries and which is perfectly inaccessible from the front. On the left

across a wooded valley is Round Top which rises 500 feet above the plain. A

stone breastwork extends from this rocky eminence to the summit of Round Top

and it was here that the enemy made their last attempt to break through our

lines or turn our left wing. In front of this battery on the rocks and within

easy rifle shot is a rocky ravine entirely destitute of vegetation and at least

100 feet below the guns. The Rebels held this ravine and from behind the craggy

rocks poured a destructive fire upon the gunners. A column was ordered to pass

to the right and left of the battery and charge upon them. This was done in the

most gallant style and those who were not killed were driven back over the

slope of the hill nearly a mile and the position was held by our troops.

In this ravine

the most horrid effects of the battle are to be seen. So many days elapsed

before the wounded could all be picked up that when the burial corps reached

the spot the bodies of the dead were so decayed as to be immovable and as there is

no earth among the rocks to cover them with. Some have a few flat stones thrown

over them but most of them lay just where they fell or where they crawled after

falling. So revolting was the sight and so sickening the smell that I retraced

my steps after passing only part of the way down the ravine. All those who

remain unburied are rebels.

In the rear of

the Rebel line, they buried their own dead before retreating by piling up large

numbers of bodies and covering them with earth. Scores of these mounds are seen

just below the ridge and on approaching them the earth was found washed away by

the heavy rains and heads, feet, and arms were exposed to view. The woods in

the rear of their batteries are literally mowed down by our shells, fragments

of which lie scattered over the ground which is everywhere furrowed by these

death dealing missiles.

The level valley between the hostile armies varies from three-fourths to a mile in width. Every foot of this ground was fought over and over again by the contending legions and every fence rail is perforated with bullets. On every part of the battleground men and women are met, some there to gratify an idle curiosity, and other seeking the graves of friends who fell on that terrible day. I cannot find space to describe the field on the right wing but as the hottest battle raged on the left, a description of this must suffice. Long after the present generation has passed away the husbandman will plow up relics of this deadly strife which will be laid aside as a memento of the great rebellion.

Source:

Letters from George G. Washburn, editor of the Elyria

Democrat, Elyria Democrat (Ohio), July 22, 1863, pg. 2, also, July 29,

1863, pg. 2

Comments

Post a Comment