We Generals Must Take Our Chances With the Boys: With General Hurlbut at Shiloh

Before the battle of Shiloh, General Stephen A. Hurlbut of Illinois earned the reputation among his volunteers as a heavy drinker, someone not to be relied upon in action. His conduct during the first day of Shiloh changed all that as relayed by Captain Smith D. Atkins of Hurlbut’s staff.

“General Hurlbut, mounted on his gray horse with

shabrack, sash, uniform, and trappings, a prominent mark for the enemy’s fire,

rode backward and forward along the line, entirely heedless of the storm of

bullets that he was drawing about himself, encouraging his men and directing their

movements,” Atkins noted. “When cautioned that his prominent appearance was

drawing the enemy’s fire, he only remarked, “Oh well, we generals must take our

chances with the boys.” Hurlbut’s courage inspired the troops, and even those

who disliked the native South Carolinian conceded he had won them over. “General

Hurlbut did his duty and stood by us like a man,” one soldier from the 3rd

Iowa commented while another said “it is due to Hurlbut to say that for once he

was not drunk and that he performed his part well.”

The three brigades of Hurlbut’s division, the First under Colonel Nelson G. Williams, the Second under Colonel James C. Veatch, and the Third under Brigadier General Jacob G. Lauman saw intense action near the Peach Orchard and the Bell Cotton Field on the afternoon of the 6th, with General Hurlbut right up front in the mix with the troops. The following account, written by Captain Atkins who was serving as Hurlbut’s acting assistant adjutant general, was written a week after the battle as Atkins was returning home on leave to recuperate his health. Directed to Hurlbut’s wife Sophronia in Belvidere, Illinois, Atkins assured her that her husband conducted himself heroically and passed through the battle unscathed. The letter first saw publication in the April 22, 1862, edition of the Belvidere Standard.

Cairo, Illinois

Sunday, April 13, 1862

Mrs. S.A. Hurlbut,

As I was an

aide to General Hurlbut in the fierce battle of Pittsburg, I doubt not a few

lines from me stating the part taken by him and his division in that battle

will be interesting to you and that you will excuse the liberty I have taken of

addressing you on that subject. Mail facilities are not the best at Pittsburg

and the General is too busily engaged to write particulars, even to you, at the

present time.

On Sunday

morning the 6th instant at about 8:30, it was first known at General

Hurlbut’s headquarters that there were any signs of an attack by the enemy upon

our lines and in five minutes more a courier came post haste stating that

General Prentiss was engaging 300 of the enemy. General Hurlbut immediately

ordered the long roll beat in his division and within 10 minutes the whole

division was under arms, the General and his staff mounted, and an order to

send one brigade to the support of General McClernand. The other two brigades

were led in person by General Hurlbut with six companies of cavalry and two

batteries to the support of General Prentiss.

The column had not advanced

above half a mile on the march out before it met the entire division of General

Prentiss drifting in upon us in full retreat. His division, being in the

advance and composed almost entirely of new troops, was completely surprised by

the enemy while at breakfast and were driven by the enemy almost without

resistance. No appeal to these troops was sufficient to cause them to stop and

again face the enemy. One battery of General Prentiss’s artillery was turned

about by General Hurlbut and given a splendid position to play upon the

advancing columns of the enemy, but after one fire the whole battery, cannoneers

and postillions, left guns and horses and fled in the wildest confusion. The boys

of Mann’s battery in our division [Battery C, 1st Missouri Light

Artillery] left their battery and spiked the guns so deserted, cut the horses

loose, and broke the coupling to the gun carriages.

Here we met General Prentiss, a

brave and good officer who, at the request of General Hurlbut, led up one of

his brigades and General Hurlbut the other, forming a line of battle to stop

the advancing foe while the staff of General Prentiss tried with only partial

success to rally his division in a line behind ours and in our support. Our

batteries were soon playing upon the enemy and theirs upon us. Shot and shell

flew thick and fast, the enemy playing from superior rifled guns and their

cannoneers evidently understanding their business well. Mann’s battery was

served with superior skill and did most terrible execution.

Their columns were soon close

enough for musket range and the enemy boldly advancing, a terrible fire of

small arms was opened along the whole line while the artillery poured grape and

canister into their ranks, the enemy stoutly resisting, emboldened by their

previous success in driving the division of General Prentiss. General Hurlbut,

mounted on his gray horse with shabrack, sash, uniform, and trappings, a

prominent mark for the enemy’s fire, rode backward and forward along the line,

entirely heedless of the storm of bullets that he was drawing about himself,

encouraging his men and directing their movements. When cautioned that his

prominent appearance was drawing the enemy’s fire, he only remarked, “Oh well,

we generals must take our chances with the boys.”

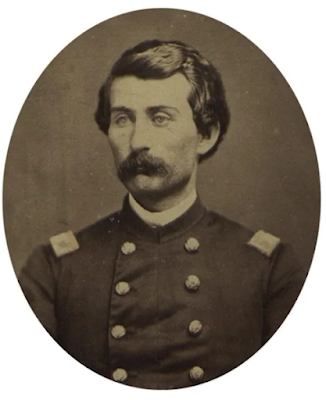

|

| General Benjamin M. Prentiss |

The enemy soon found they had

new troops to encounter and, falling back, planned their attack more

skillfully, bringing to their assistance more batteries of artillery. Wherever

a new battery opened, there rode General Hurlbut, directing the planting of a

new battery to meet its fire. Occasionally under the fire of some battery, a

terrible assault with musketry would come from the enemy upon some supposed

weak point of our lines, to be met by the steady, stern resistance of the brave

troops under his command.

For five hours, General Hurlbut

with those two light brigades and without support not only stopped the enemy

who was flushed with victory, but successfully held him in check, checkmating

his generalship, and driving him back wherever he chose to assault our lines. We

only fell back at last when the enemy by his superior numbers was enabled to

outflank him on either side and place him within the range of three fires, and

even in the falling back, he gave him as good as he sent, forming new lines of battle

on every position that the ground made favorable and contesting his advance

inch by inch.

General Hurlbut formed his last

line about 4 p.m. flanking the siege guns which were planted about a half mile

from the riverbank and planting his light artillery and all he could pick up in

three different positions so as to open a crossfire from three ways upon the

enemy. He determined to stand by those as his last hope. Scarcely were his

preparations ready when the enemy appeared above the brow of the hill, but was

quickly driven back by the concentrated fire of those screaming batteries and

each time he advanced, it was only to retire again under that murderous storm

of iron missiles. The gunboats getting the range of the enemy’s lines, chimed in with their heavy booming, a music that was joy to our boys and

with their massive shells sent havoc into the enemy’s lines.

Night soon closed in upon the

scene and by the order of General Grant, General Hurlbut moved forward his line

of battle about 300 feet into the ravine in front of the batteries where the

order was given to lay upon their arms all night, sending out skirmishers

prepared at any moment to resist an attack by the enemy. The gunboats kept up

their fire with their heavy guns, throwing shells alternately with 12- and

20-second fuses up the ravine and in front of our lines, effectually keeping

the enemy from making any advance. Too much credit cannot be given to these

ironclad monsters of the river that sent terror into the ranks of the secesh

wherever their heavy voices are heard.

During the night General Lew Wallace

with his entire division reinforced us from Crump’s Landing and General Buell

crossed over to our assistance. These new troops took the advance in the

morning, General Wallace on the right and General Buell on the left, and

steadily drove the enemy before them with the assistance of the troops yet

left. General Hurlbut got his division in fighting trim early after breakfast

and I rode along in front of the lines with him. Many familiar faces had gone

since the morning before: Colonel Ellis and Major Goddard of the 15th

Illinois killed dead upon the field and that gallant regiment, led

by Captain Kelly, only about 200 strong. The 3rd Iowa had

all of its field officers killed or wounded, and all of its captains killed,

wounded, or missing, and less than 200 strong were in command a first

lieutenant as ranking officer. An order soon came to General Hurlbut to support

McClernand’s right and General Hurlbut put his division in motion, himself at

its head, and pushing forward was met by an aide of General McClernand and

directed to his left where the enemy was flanking McClernand’s division. We

arrived just in time to save his left flank from being turned. [McClernand and

Hurlbut had a nasty feud develop during the movement to Pittsburg Landing in

mid-March.]

The writer was in the engagement

at Fort Donelson and supposing that he had passed through as terrible a fire as

it was possible to do and escape, but I must confess that the assault of the

Rebels upon our lines was the most recklessly desperate of which the

imagination can conceive. It seemed as if the inspiration of devils was infused

into the ranks of both armies. Some of the ground in this vicinity was fought

over as often as six times, so desperately determined were each to maintain it.

General Hurlbut, as well as General McClernand, was always to be found where

the fire was hottest directing the movements and lending encouragement by his

presence. About this time General Hurlbut’s gray horse was shot and he mounted

a bay, and the writer confesses he was glad of it for the General’s sake for

the gray seemed to be a special mark.

The enemy’s effort seemed specially

directed to flanking us, and he was ever attempting it under the cover of the

many hills and ravines; and at one time, within one hour, our line of battle

changed front three times. So confident were the enemy of victory on the night

previous that when in possession of our tents that they did not destroy them,

being certain to keep them for his own use and it is a well-ascertained fact

that General Beauregard had his headquarters that night in the large office

tent of General Hurlbut’s, but save the holes torn by the bullets, it was

uninjured and occupied by General Hurlbut on the following night.

Although the enemy stoutly

resisted, he was all the time driven back on Monday and 4 p.m. his fire had

entirely ceased along our whole line, and our cavalry and artillery pursuing

him in his flight. I left Pittsburg Landing on the 11th and

everything was then quiet. The reports had not all come in from General Hurlbut’s

division, but his estimated loss was over 500 killed and 1,800 wounded and

missing. General Hurlbut was struck by a spent musket ball on his left arm but

save that received no injury. He had many narrow escapes. The writer saw a

rifle shot strike a tree within a few feet of his head, eliciting the remark

from him, “They have got our range pretty well.” At another time a shell burst

within 10 feet of him but he was not scratched by it. His courage and coolness

under fire, and his entire disregard for his personal safety were remarked by

all under him, and by his bravery and skill in this engagement he was won the

love and confidence of the brave troops he has the honor to command.

I have only to add that this letter

is a poor apology and that the health of General Hurlbut on the 11th

instant was good. Long may he live to serve his country and add honor to its

victories.

I am madam, very respectfully,

Smith D. Atkins

Captain Atkins would serve throughout the war

with great distinction. Appointed colonel of the 92nd Illinois in

the summer of 1862, the regiment would go on to great renown as a member of

Wilder’s Lightning Brigade in the Army of the Cumberland. Atkins would

eventually earn a brevet promotion to major general.

Source:

Letter from Captain Smith Dykins Atkins, acting assistant

adjutant general of the staff of Brigadier General Stephen A. Hurlbut, Belvidere

Standard (Illinois), April 22, 1862, pg. 2

Comments

Post a Comment