Sunbrowned and War-Worn Stalwarts: A Character Study of Western Federals

"They are tall, stalwart fellows, looking rather thin, sunbrowned, and war-worn. But there was something in the firm step, intelligent look, and resolute bearing of those tall, sinewy, iron-framed warriors that showed the thinking mind, and unfailing energy of the true soldier.” ~ New York Daily Herald, May 25, 1865

During the Civil War, observers noticed a distinct difference between eastern theater and western theater Federal soldiers. As the war progressed, the differences between the two grew more nuanced but stood in stark relief during the Grand Review of the armies in May 1865. As the Cleveland Morning Leader stated “though somewhat behind their brother Army of the Potomac in dress which could not be well-supplied on account of their long, incessant marches, in marching, physique, and soldierly bearing they favorably compared with them. They are tall, stalwart fellows, looking rather thin, sunbrowned, and war-worn. But there was something in the firm step, intelligent look, and resolute bearing of those sinewy, iron-framed warriors that showed the thinking mind and unfailing energy of the true soldier.”

D. Reid Ross

noted in his 2008 article on the Grand Review that “the spectators and

reporters who stayed over the second day consistently noted that Sherman’s “wolves”

were taller, they looked older and stronger, and their marching stride was

several inches longer. Even General Meade’s officers conceded that Sherman’s

men marched better, their faces were more intelligent, self-reliant, and

determined. Overall, Sherman’s slouch hats overtopped the easterners in their

physical appearance and soldierly bearing.”

This begs the

question: what made western Federals different from their eastern theater

comrades?

The very term “western Federals” denotes soldiers who fought anywhere

west of the primary eastern theater fighting in eastern Virginia. This broad

swathe of territory stretching west from the Appalachian Mountains to the

Rockies encapsulated thousands of square miles of territory, much of it only a generation

removed from the frontier. For the purposes of this review, I’d like to keep

the focus on the two primary Federal armies that fought the war between the

Appalachians and the Mississippi River: the Army of the Cumberland and the Army

of the Tennessee.

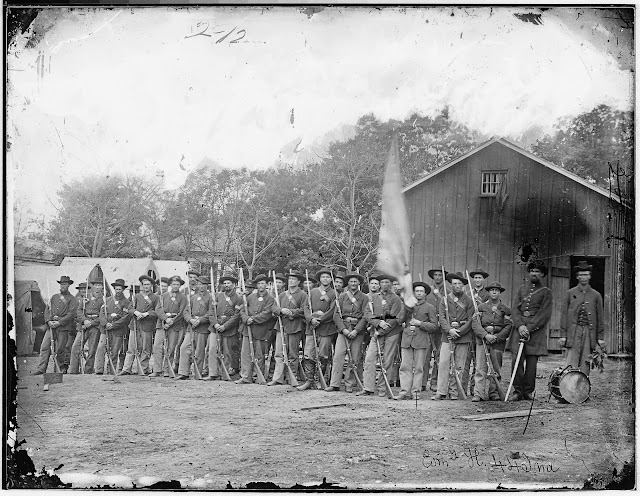

|

| Private James Cunningham 8th Missouri |

That there were distinct differences should come as little surprise. As the war progressed, these characteristics tended to become more nuances than stark black-and-white differences.

First let's look at leadership. The popular perception of the Army of the Potomac is that it was a spit-and-polish very Regulation Army outfit. That tone of pomp and circumstance was set early by General George McClellan who insisted on both a snappy appearance of his troops as well as strict adherence to the regulations in all respects. As the war progressed, the soldiers of McClellan’s army grew into veterans just like their western comrades which tended to erode some of the early spit-and-polish, but the differences remained throughout the war.

In contrast to the Army of the Potomac was the Army of the Tennessee which was led for much of its existence by both Generals Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman. Both Ohioans adopted a less formal style of both command and dress, and their subordinates followed their lead and adopted the same manner with the rank and file. In the Army of Ohio (which became the Army of the Cumberland in early 1863), General Don Carlos Buell struggled to get his freewheeling westerners to follow the regulations which led, in part, to Buell’s steadily worsening popularity with the men after Shiloh. Buell's injunctions and punishments against foraging (while his men suffered on half rations or less) rubbed against the grain and ruined Buell's reputation with his men. His replacement William S. Rosecrans was no softie on discipline but possessed a finer touch with his western volunteers and proved a far more popular commander.

Secondly, the very nature of the campaigns in the west added their own flavor

to both the appearance and conduct of the western federals. From the beginning, the westerners were an army on the move, their campaigns marked by

lengthy marches traveling vast distances far removed from bases of supply. The men grew hardier under

the strain or broke down completely and eventually left the army. The long

marches and time away from camp tended to impact not only discipline (generally

looser in the west) but appearance as well. The western preference for slouch

hats and other wide-brimmed hats stemmed from the fact that a forage cap or

kepi provided little if any protection from the sun; the men simply needed

better cover while on the march.

|

| Private Horace H. Smith, 16th Wisconsin |

The need for comfort on the

march also led to western Federals preferring sack coats versus frock coats;

the men tended to gravitate more towards utilitarian garments versus ones that

provided a fine appearance. Westerners typically wore less hat brass than their

eastern comrades, and the idea of wearing corps badges didn’t really catch on

in the west until after the battles for Chattanooga when the westerners were

introduced to corps badges by their new comrades in the 11th and 12th

Corps from the Army of the Potomac. However, many western Federals posed to get

their “likeness” taken wearing frock coats complete with regulation Hardee hats,

much like their eastern comrades. Once again, leadership at the regimental,

brigade, and divisional level generally set the tone as far as standards of

dress.

The roving nature of their campaigns squared with the pre-war experiences of many of these western troops. Everyone in the western army was one or at most two generations removed from the frontier; many of the soldiers from places like Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, Missouri, and Kansas were actively living a frontier lifestyle when they joined the army. That said, these men tended to adopt a more pioneering and adventurous spirit, were less settled in outlook, rather restless, tended to be freewheeling, independent in thought and action with a devil-may-care attitude. Educational opportunities lagged in the western U.S. at this time, so the men tended to be a bit less educated in the aggregate than their eastern comrades.

In general, the composition of

the armies in the west tended to feature less trades and businessmen and more

farmers than in the east. These farmers were used to not only hard work but also

were used to being their own boss which made them more apt to question their

superiors, and consequently less apt to conform to discipline. In many ways, western Federal attitudes and outlooks tended to

coincide with their western Confederate opponents more so than their eastern

Federal comrades.

Captain Benjamin Stone from the 73rd Ohio of the 11th Army Corps of the Army of the Potomac observed when he arrived in Tennessee in October 1863 that the Army of the Cumberland was “very brave. It fights well but is very loose, unsystematic, undisciplined, and confused. Its business departments are loosely managed and its whole method of working is slovenly. It takes something besides courage to make an army.” Stone’s observation touches on the freewheeling nature that became a hallmark of the western Federals; the men tended to fight on their own hook once the shooting started and the independent nature of the men made them a little more willing to take initiative lower down in the ranks. The nature of their wide-ranging campaigns tended to drive the men to forage more heavily upon the countryside and the men subsequently adopted a hard-war posture earlier than their eastern comrades.

Rank and file western Federals

often felt like second-class citizens compared to their comrades back east. The

western troops usually had to utilize older weapons and had a lower priority on

equipment than the Army of the Potomac. Despite this apparent handicap, the men felt that they were better

fighters than their eastern comrades and pointed to their successful war record

with a great deal of pride. Repeated victories over the Confederate armies in Tennessee, Mississippi, and Georgia stood in stark contrast to the repeated defeats suffered by the Army of the Potomac. Over time, the westerners developed something of a chip on

their shoulders as they forged their own identity as rough and tumble soldiers

who never got the credit they deserved from both the press and the public. That focus on the eastern theater carried on well into the late 20th century and it is only in the past 30-40 years that this "eastern theater bias" as begun to shift.

Regardless, as time went on, the western Federals earned grudging respect from their Confederate opponents who clearly could tell the differences between western and eastern Federals. One Confederate from the 47th Georgia recalled telling an eastern comrade at Chickamauga that “you ain’t fighting Dutch and Downeasters like you’ve been used to in Virginny.” Robert Anderson of the 2nd Kentucky likewise told one of Longstreet’s men “them fellers out thar you are goin’ up against ain’t none of the blue-bellied, white-livered Yanks and sassidge-eatin’ forin’ hirelins’ you have in Virginny that run at the snap of a cap. They’re western fellers and they’ll mighty quick give you a bellyful o’ fightin’.” I think most western Federals would have smiled at that last comment and taken it as a hard-earned compliment.

Sources:

“The Grand Review,” Cleveland Morning Leader (Ohio),

May 25, 1865, pg. 1

“The Review: Sherman’s Veterans on Parade,” New York Daily

Herald (New York), May 25, 1865, pg. 1

Comments

Post a Comment