A Golden Preservation Opportunity at Stones River

The Battle of Stones River, one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War, has suffered from a lack of battlefield integrity which has hampered efforts to properly interpret the engagement. To be sure, the National Battlefield today encompasses less than 700 acres of a field which stretched more than three miles in length.

The whole of the ground fought over by the Federal Right Wing and men from Hardee’s and Polk’s Corps on the morning of December 31, 1862, has been overrun with highways, rampant development, and has been thought all but lost. Gone forever. Until now.

The American Battlefield Trust is currently engaged in a campaign to secure 32 acres of core battlefield land located to the east of Gresham Lane just north of its intersection with Tennessee 96, which during the battle was the Franklin road. As shown on the map below, it is a tract surrounded by homes and businesses, but it presents a wonderful (and unique) opportunity to preserve a small portion of this crucial portion of the field.

And make no mistake- the soldiers in the Blue and Gray fought over this property in the early morning hours of December 31, 1862. As a matter of fact, some of the first shots of the battle were fired on this property as the Federal skirmishers from General Edward Kirk’s brigade discharged their pieces at General Evander McNair’s Arkansans that emerged from the early morning fog that day.

Skirmishers from the 77th Pennsylvania opened fire on the Arkansans but the Confederates “paid not the slightest attention to it,” one Pennsylvanian reported “but kept steadily on singing as they came. Enough words could be distinguished that the song was something about Southern rights,” he wrote. Captain William A. Robinson recalled that the Confederates charged past with “their hats pulled over their eyes as though afraid to look at what was before them. The enemy swept past us by thousands.”

Among those singing on the attack was Captain John O’Brien of the 30th Arkansas. “Our first dash at them had somewhat disarranged our line, some of it having come in contact with large fences the enemy had thrown together for a sort of breastwork,” O’Brien wrote. “The Yankees all this time were firing on us from the cedars and doing considerable harm. At this moment, General McNair came dashing along the lines and told us to charge the cedars. Our men again raised their fearful yell and charged headlong amidst a shower of shells, shot, and Minie balls.”

McNair’s attack shattered Kirk’s brigade but it came at a cost, among those wounded being Captain O’Brien. As he lay upon the ground near the wreckage of Kirk’s brigade waiting for the Confederate infirmary corps to carry him off to a field hospital, Colonel Peter Housum’s counterattacking 77th Pennsylvania appeared.

“I lay there in a state of stupor and bewilderment and all this time the infirmary corps never made their appearance,” he recalled. “Around me lay in all forms and attitudes the dead and wounded, the principal part of which were Yankees. I began to wonder how long I’d have to remain here when I thought I heard a bugle sound close behind me. I listened and, in an instant, I heard a discharge of musketry. With the aid of my saber, I got up from the ground and strove to hobble off. I hopped a few steps when again the fire was repeated behind me and I could distinctly see the leaves on the ground pop all around me as the bullets struck them.”

Adjutant Samuel Davis of the 77th remembered this wild charge. “With a yell, the regiment pitched forward on a full run shoulder to shoulder amidst a storm of shot, shell, grape, and canister,” he wrote. “When about two-thirds of the distance and while crossing a fence, the colors fell and with the color bearer Sergeant Scott Crawford pierced by several balls [Crawford was shot in both legs and died that day]. Scarcely had they touched the ground before willing, brave, and strong arms flaunted them to the breeze in the face of a defiant foe.”

|

| The target property is located on the east side of Gresham Lane just north of the intersection with the very busy Tennessee Highway 96. (American Battlefield Trust) |

Ahead lay the four guns of Captain James Douglas’s Texas battery, moving up in support of the Confederate assault. Colonel Housum’s counterattack caught the Texans in the open without immediate infantry support.

“When we got about halfway, we came to a lane with fences on both sides,” Charles Cope of the 77th wrote. “The battery was all ready and threw a lot of tin cans on the ground in front of us and they broke open and scattered cast-iron balls and knocked the fences down so could come over without climbing. Very accommodating!”

The Pennsylvanians charged to within yards of Douglas’ Texans. “On we rushed and when within a few yards our guns discharged a volley of leaden hail which almost completely annihilated the Rebels who were pouring missiles of death among us from our own guns,” Adjutant Davis continued. “Edgarton’s battery was again in our possession and a deafening cheer went up from every throat which was loud enough to be heard above the din of battle. No attention was paid to the captured guns, but straight on to the other battery flushed with what proved to be only an apparent victory. We continued to advance under a raking fire of grape and canister until we were suddenly confronted by a largely superior force concealed in the edge of the woods.” It was Bushrod Johnson’s and Lucius Polk’s brigades of Cleburne’s division.

|

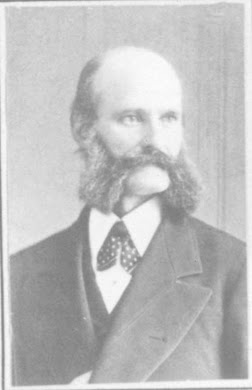

| Captain William Robinson 77th Pennsylvania |

To be sure, the Pennsylvanians were surprised to find themselves out in the field alone. “We found ourselves suddenly faced by a heavy force of infantry close upon us and sure of capturing us,” Captain William Robinson wrote. “Turning our eyes to the rear for the first time, we found we had no support at all and were nearly half a mile in advance of any of our forces!” Colonel Housum had the regimental bugler sound retreat, and the Pennsylvanians ran back pummeled by repeated rounds of canister.

The 2,016 men of Bushrod Johnson’s Tennessee brigade deployed into battle line, then turned north to pursue the Pennsylvanians. In the process, the right flank regiments of Johnson’s line (37th and 44th Tennessee) marched right over the target property before they found themselves squarely facing Colonel P. Sidney Post’s line with a cornfield between them; the still standing cornstalks permitted line of sight for both sides to eye their opponents 300 yards away.

Captain Oscar Pinney’s 5th Wisconsin Battery at the center of Post’s line opened fire “with all his guns and when they came within range of his canister and the fire of the supporting regiments, the execution was so great that the entire line recoiled before it, but after temporary confusion, they were rallied and lay down,” Colonel Post recalled. Lieutenant Chesley Mosman of the 59th Illinois stood watching the approaching Rebels so intently that it wasn’t until the first volley was fired that he remembered to lie down. “We fired like thunder and stopped the Rebel advance and made them lay down, too,” he wrote. “The Rebels on our left came, not stopping until within a hundred yards when they came to a halt.” A veteran of the 74th Illinois stated that “the enemy commenced firing at long range, but heedful of the good advice we were given, the regiment reserved its fire until they were close open us and then opened with volley after volley which made the solid lines recoil. With undaunted courage the Rebels came on and we could plainly hear the commands ‘forward and close up’ amid all the din of shot and shell.”

The 37th Tennessee arrived at the southern edge of the cornfield facing the 74th and 75th Illinois already rattled from having their two commanding officers knocked out of action during the march into position, shot down by riflemen from the 77th Pennsylvania. Major Joseph T. McReynolds took command and after sending out skirmishers to prevent a repeat of the kind of surprise the regiment just experienced when orders arrived to move forward. The Tennesseans held the brigade’s right flank and had to march through the cedar thicket that had previously concealed Kirk’s men.

“The enemy retreated back to a cedar glade where they had several pieces of artillery planted,” Captain Charles G. Jarnagin reported. “Owing to the advantageous position the enemy held, we did not pursue them immediately but moved by the left flank into a skirt of woods and there formed a line of battle and moved forward. We charged across to a cedar thicket and met with a warm reception.” The Tennesseans started taking flanking fire from the 75th Illinois to their right as they approached the Federal line, and McReynolds ordered the 37th to fall back. McReynolds was mortally wounded while retreating which made Captain Jarnagin the regiment’s fourth commander that morning.

The fight between Johnson and Post’s brigade, with a good portion of Johnson’s line stretching across the target property, turned into a slugfest. Johnson described it as some of the toughest of the battle and reported that he suffered his heaviest loss of the day right here. And now we have an opportunity to secure this property to help tell this incredible story of the Battle of Stones River.

David Duncan of the American Battlefield Trust states in a recent letter that “now we have the chance to save this hallowed ground. It’s one of the single largest undeveloped tracts remaining on the battlefield! The land was recently listed for sale as prime commercial property, and the surrounding area is overrun with commercial, industrial, and residential development. Murfreesboro is one of the fastest growing cities in the United States and there is a huge and growing demand in this exact area. If we don’t win it now, it could be gone forever.”

Gone forever is a story that is all too familiar with Stones River. Over the years, nearly all of the land on the south side of the battlefield has been lost to development. But today we have a chance to make a difference and secure an important property that will finally allow proper interpretation of the opening of the Battle of Stones River.

The ABT is currently campaigning to raise the $421,000 needed to secure both this 32-acre tract and 152 acres at Shiloh. More than $8 million of funding in the form of government grants and pledged gifts has already been raised to secure these properties- it’s up to us to get the effort over the hump.

I will be donating on Monday. I humbly ask that you please consider donating to this effort, the link to which is below. Online donations given through Tuesday November 28th will be matched dollar for dollar by a generous fellow supporter of saving this sacred ground.

Save 184 Tennessee Western Theater Acres at Shiloh and Stones River.

Comments

Post a Comment