Victims of an Inglorious Disaster: A Yankee’s Vivid Account of Brice’s Crossroads- Part 1

Looking back on the events of Sturgis's campaign in northern Mississippi 25 years later, Ira F. Collins of the 114th Illinois was struck by the complete change of fortunes wrought upon the battlefield by incompetent generalship. And he laid it at the feet of General Sturgis's affinity with the bottle.

"No force ever marched forward with more confidence than did the one under General Sturgis on that bright June morning," he wrote. After double quicking for five miles to arrive on the battlefield, Collins noted that General Sturgis had taken over the Brice House at the crossroads as his headquarters. "I afterward saw it stated in a Mobile paper upon the authority of Mrs. Brice that Sturgis was drunk during the fight and indulged frequently during his brief stay. This being from a Rebel source might be somewhat exaggerated, yet there is no one who was in the battle of Guntown but believes that Sturgis was drunk and utterly unfit and incompetent to command during the battle. The only strange and remarkable thing about it is that he escaped the exasperation and wrath of his own men that day."

With this introduction, Collins, then senior vice commander of the Kansas Department of the Grand Army of the Republic, penned a fine memoir of his subsequent experiences at the Battle of Brice's Crossroads which included not only being wounded in the head during the battle, but captured the following day during the retreat. His vivid account of personal experiences during Sturgis’s June 1864 expedition into northern Mississippi was originally published in subsequent issues of the Western Veteran newspaper in July 1889.

Due to the length of Collins' account, this is a two part post. To read part 2 "My Last Shot at the Confederacy: A Yankee's Vivid Account of Brice's Crossroads," click here.

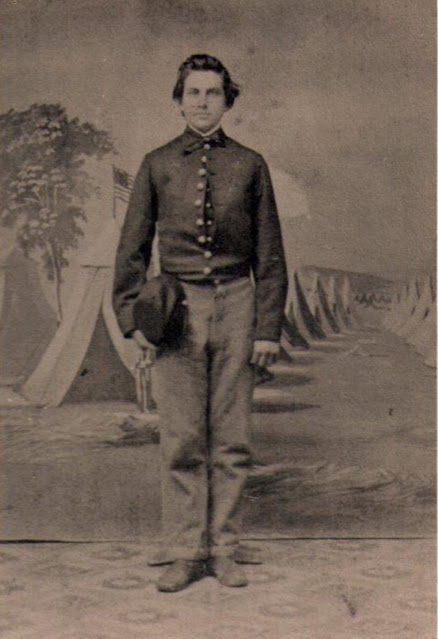

|

| Private Ira F. Collins, Co. D, 114th Illinois Volunteer Infantry |

The 10th

day of June 1864 will long be remembered by that little army of 7,000 soldiers

marching under the command of Brigadier General Samuel D. Sturgis through

northwest Mississippi. This little army consisted of two brigades of cavalry,

mostly non-veterans of several old regiments that were home on veteran

furlough, and three small brigades of infantry. Following this army was a

supply train of 256 wagons.

With the exception of two

colored regiments, the soldiers composing this army could be called veterans as

every one of them had seen service and marched under the victorious banners of

Grant and Sherman. They were inured to hardships and privations, had tramped

through long marches, and had fought at Shiloh, Corinth, Vicksburg, and

Jackson; some fought with Banks through the Red River campaign. They were

soldiers tried in the fire of battle and many victories marked their banners

cheering them on to the new conquest. The rattle of a few muskets on the

skirmish line made them as eager for the fight as the trained horse for the

race.

Our marching

equipment was of the fewest and simplest kind as long experience had taught us

to discard everything not an absolute necessity, and it is surprising to the

inexperienced the small amount of rations, clothing, cooking utensils, and

other paraphernalia the average soldier could get along with after he had a few

months experience in the field. The whole amount of his outfit would not weigh

more than 8 or 9 pounds shown as follows: hardtack, 3 lbs., coffee ¾ lb., sugar

1 lb., oyster can ¼ lb., half canteen ¼ lb., poncho/gum blanket, 2 lbs. These

rations would be about a three-day supply, the usual amount drawn by the

soldier just before starting on a march as it was not safe to risk drawing only

a single day’s ration on account of the uncertainty of the supply train putting

in an appearance on time. It may be in the foregoing estimate is too small, yet

you can readily see what a small amount of marching equipment the soldier in

the field truly needed. This was, of course, for a summer campaign. In a winter

campaign, there would be the addition of an overcoat and woolen blankets. This,

with the musket, cartridge box, and two pounds of ammunition at all times made

up the soldier’s marching outfit.

|

| One of the most important pieces of field gear on the Guntown campaign was a soldier's canteen. Marching through the heat of humidity of a Mississippi summer made for a miserable experience. |

This force

left Memphis, Tennessee on the 1st day of June 1864, and from the

number of ambulances and the long wagon train accompanying the expedition an

old campaigner would conclude at once that the campaign was intended to be a

long one. It was generally supposed among the troops that it was the intention

for us to either march across the country and join Sherman before Atlanta or

else move into the enemy’s country and by engaging the attention of the cavalry

under General Forrest prevent him from joining Johnston’s forces and annoying

the rear of Sherman’s army. But whatever Sherman’s intentions were in ordering

out this expedition, we never even dreamed of the fate that was in store for us.

No force ever

marched forward with more confidence than did the one under General Sturgis on

that bright June morning. The country through which we passed had originally

been heavily timbered and the plantations had been formed by clearing the

timber off. The heavy belts of timber still standing prevented an extended view

of the surrounding country and made the route favorable for Rebel scouts to

observe our movements and determine the number of our forces.

Nothing occurred

to interrupt the steady march of the command until near noon on June 10th

when the report came back that the cavalry was being annoyed by the Rebels in

front. The rest of the cavalry was at once ordered forward to clear the road

and it was not long until the rattle of musketry told us that the Johnnies were

disposed to measure strength with the Yanks. The infantry was put on the double

quick and after a run of five miles came up to the cavalry and found that the

Rebels had made a stand and the cavalry was unable to dislodge them.

The misfortunes of the infantry

had already begun. During the long double quick march under a broiling Southern

sun, many who became sun struck and overcome with the heat were laid in the

fence corners or in the shade of trees and left for the ambulances to pick up.

Many of them were beyond the pale of human assistance long before the ambulance

corps came to their relief and lay there by the wayside with their bloodshot eyes

staring into vacancy, blotched skin, swollen lips and protruding tongues, a

lifeless mass of flesh and blood, the first victims of the inglorious disaster

brought about by our drunken incompetent commander.

We crossed

Tishomingo Creek, a slow sluggish stream two or three rods wide, and

immediately formed a line of battle. We divested ourselves of haversacks and

luggage, piling them in one common heap and two men from each company were

detailed to carry water for the rest. These took possession of all our canteens and

this was the last I ever saw of the detail, haversacks, or canteens, and was destined

to be the last time I carried a canteen during the war.

Moving forward

to the brow of the hill, we came to a crossroad running north and south. There

were three buildings situated in the three of the corners formed by the

crossroads. One of these, a large two-story frame house painted white and owned

by a Rebel named Brice, was taken by General Sturgis as his headquarters. I

afterward saw it stated in a Mobile paper upon the authority of Mrs. Brice that

Sturgis was drunk during the fight and indulged frequently during his brief

stay. This being from a Rebel source might be somewhat exaggerated, yet there

is no one who was in the battle of Guntown but believes that Sturgis was drunk

and utterly unfit and incompetent to command during the battle. The only

strange and remarkable thing about it is that he escaped the exasperation and wrath

of his own men that day.

One of the

three buildings before referred to was a small church or schoolhouse; I cannot

say positively which as our time for making examinations and investigations was

short. Our forces came in on the road running to the east, the crossroad

running north and south. The Brice house was in the northwest corner, the

church on the northeast, and an old, hewed log cabin on the southwest, all in

front being woods with a considerable growth of underbrush making it difficult

to see but a short distance. We formed in line of battle at this crossroads. In

a few minutes, the cavalry front fell back and we were ordered forward. We

advanced 600-800 yards under a brisk fire from the Rebel sharpshooters. We took

position and attempted to return their fire with but poor success, they being

well-sheltered behind logs and trees while we were in the brush and young

timber that afforded but little protection.

Back at the crossroads, the Waterhouse battery

was sending solid shot and shell over our heads into the woods where the Rebels

lay in front of us. To the left could be heard Captain Kidd’s 4th

Indiana Battery sending their compliments to the Johnnies while the Rebel

batteries answered in quick succession, hurling their death-dealing missiles

into our ranks, making grand and awful the play of battle. Then there came an

ominous silence like the calm just before the bursting of a storm which is

harder to endure than the charge itself. The experienced soldier understands

full well what is to follow. Every muscle is strung to its highest tension and

with bated breath and beating heart, the soldier awaits the expected assault.

To add to our

disadvantage and discomfort of having been drawn into a trap by the Rebels and

compelled to give them battle on their own chosen ground and against

overwhelming odds, the infantry had been double quicked five miles and as each

regiment came up it was ordered to the right or left and fought in detail

without knowing whether it was properly supported or not. At least was the case

with my 114th Illinois for we were not long in the brush until we

were being raked by an enfilading fire and soon discovered that we were the

center of attraction for a large force of Rebels that occupied a position

around us about the shape of a horseshoe. We were relatively without support on

the right and left.

Under these circumstances, we were not long in making up our minds that discretion was the better part of valor and we back to the crossroads and took a position in support of the Waterhouse battery. Here we made a gallant stand and did some good work against fearful odds, but that everlasting horseshoe was fast closing around us. General Sturgis’s headquarters had disappeared from the house. No aide-de-camp came to reorganize our broken lines or give us a cheering encouragement that support was at hand, and it seemed to us that the Waterhouse battery and the 114th Illinois were running a battle all along against the whole Southern Confederacy with the chances of victory largely in favor of the Confederacy.

Click here to read Part 2: My Last Shot at the Confederacy: A Yankee's Vivid Account of Brice's Crossroads

Private William C. Johnson of Co. K of the 114th Illinois wrote a superb letter detailing his experiences at Brice's Crossroads which can read on Griff's Spared and Shared page here.

Comments

Post a Comment