An Eyewitness at Carnifex Ferry

Major Robert Henry Glass, editor of the Lynchburg

Republican, witnessed the Federal advance and attack at Carnifex Ferry,

Virginia on the afternoon of September 10, 1861, impressed both with the heroism

of his comrades and that of his opponents.

“The enemy was seen swarming in

the woods from one end of our lines to the other,” Glass reported. “He approached

us from this point in double-quick time, evidently intending to force our works

at the point of the bayonet. At the first crack of our rifles the gallant

Colonel who led in front of his men, on a splendid black charger, fell dead to

the earth, while the head of his column recoiled in utter confusion. The

Colonel's horse, as if unconscious of the fall of his rider, dashed up to our

embankments and around them into our camp, and from the inscription upon the

mountings of his pistols, proved to be Colonel William H. Lytle of Cincinnati

[commanding 10th Ohio Infantry]. I saw the daring officer fall from

his horse, and he was certainly one of the bravest of the brave, for he sought

"the bauble reputation" at the very cannon's mouth.”

Major Glass’s eyewitness account first saw publication in his newspaper, the Lynchburg Republican, in late September 1861; it was widely copied in newspapers throughout the South.

Headquarters near Dogwood Gap, Virginia

September 11, 1861

On Monday last we received

intelligence of the advance of the enemy in heavy force from the direction of

Sutton, along the Summerville road. On Tuesday morning Colonel John McCausland's

regiment, which had been down at Summerville as our advance, was driven in, and

the enemy encamped fourteen miles distant from us. We expected him to drive in

our pickets on Tuesday night and attack us on Wednesday morning; but contrary

to expectations, he forced his march and drove in our pickets at 2 o'clock

Tuesday.

Our line of battle was at once

formed behind our breastworks, and scarcely had all our forces been placed in

position before the enemy was seen swarming in the woods from one end of our

lines to the other. He approached with great deliberation and firmness, and his

central column emerged from the woods and above the hills, 200 yards in our

front, just 15 minutes after 3 o'clock. He approached us from this point in

double-quick time, evidently intending to force our works at the point of the

bayonet.

At the first crack of our rifles

the gallant Colonel who led in front of his men, on a splendid black charger,

fell dead to the earth, while the head of his column recoiled in utter

confusion. The Colonel's horse, as if unconscious of the fall of his rider,

dashed up to our embankments and around them into our camp, and from the

inscription upon the mountings of his pistols, proved to be Colonel William H. Lytle

of Cincinnati [commanding 10th Ohio Infantry]. I saw the daring

officer fall from his horse, and he was certainly one of the bravest of the

brave, for he sought "the bauble reputation" at the very cannon's

mouth.

|

| Colonel William H. Lytle 10th O.V.I. |

The enemy's columns now opened

upon us along the whole of our center and right, and for an hour the rattle of

musketry and the thunder of our artillery was incessant and terrible. The enemy

was driven back and silenced for a moment, but came again to the fight,

supported with five or six pieces of artillery, two of which were rifled cannons.

For another hour and a half, the battle raged with terrific fury, and again the

enemy's guns were silenced and he driven from our view.

The sun was now fast sinking

beyond the distant mountains, and we were strongly in hopes that the enemy had

met his final repulse for the evening; but a few minutes dispelled our

illusion. For the third time the enemy came back to the conflict with more violence

and determination than before. He assailed us this time from one end of our

lines to the other and tried his best to flank us. For another hour and a half,

and until the dark curtains of night closed in upon us, the fight raged with

intense fury.

At first, the range both of

their small arms and artillery was very bad, shooting entirely over our heads.

The range of the cannon was especially bad, for while their balls cut off the

tops and split open the giant oaks in our encampment, their shells, with few

exceptions, burst high in the air and full fifty yards in our rear. But when

they came to the last charge, they had gotten the range far better, and their

balls began to plow up our embankments, while their shells broke directly over

us in every direction and with terrible fury.

The enemy seemed to be perfectly

enraged at our obstinate resistance and was determined to pour out the full

vials of his wrath upon us. The battle ceased at 15 minutes past 7 o'clock,

having continued almost incessantly for four long hours. Our men stood to their

posts with astonishing coolness and courage. The only fault they committed

during the battle was that of firing upon the enemy at too long a range, and

while too securely posted behind the dense forest trees which skirted our

entire lines.

|

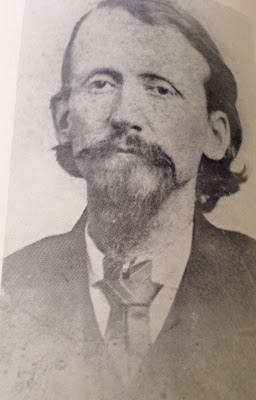

| Major Robert H. Glass Editor of Lynchburg Republican |

We did not lose a single man

killed, and not more than ten wounded. The enemy's loss could not be

ascertained, but at one single spot, where Colonel Lytle fell, we counted 37

dead bodies. The prisoners inform us that their loss was heavy, and from the

fact that we silenced their guns three times, we are confident this report is

entirely true. The prisoners also informed us that another colonel, whose name

I do not remember, was badly if not fatally wounded, and his horse killed under

him. [This would have been Colonel John W. Lowe, commanding the 12th

Ohio Infantry; he was shot through the head as he led his regiment through the

underbrush to attack the Confederate line.]

Our officers acted with great

coolness and bravery. The battle had raged but twenty minutes when our gallant

General [John Floyd] was very painfully wounded in the right arm, the ball

entering near the elbow and passing out near his wrist, without breaking any

bone. We retired with him a short distance under the hill and had the wound

dressed by Surgeon [Samuel C.] Gleaves [45th Virginia], and in ten

minutes he was again moving along our lines, encouraging his men by his

presence and his voice. At a later stage of the fight a Minie ball tore through

the lapel of his coat, and another through the cantle of his saddle. Indeed, it

is the wonder of all of us how he escaped death. --None but his staff and

surgeon knew he was wounded until the close of the fight. He is now suffering much

pain.

We had dispatched General Henry

Wise in the morning for reinforcements, and he had declined to send them for

fear of an attack upon him by General [Jacob] Cox. We had also sent couriers

for the North Carolina and Georgia regiments to come up, but it was impossible

for them to reach us in time to support us. At 10 o'clock last night,

therefore, our forces proceeded to retire from the position they had so

heroically defended during the day, and by light this morning they were all

safely and in order across the river, with all their baggage, &c., except

some few things which were lost from neglect and want of transportation.

|

| Despite holding off Rosecrans' attack, Floyd's outnumbered command abandoned the field after dark, crossed the Gauley River on flatboats and retreated south about 15 miles to camp near Dogwood Gap. |

We are now pitching our tents at

this place, on the main Charleston road, about 15 miles from Gauley Bridge, and

55 miles west of Lewisburg. General Wise is encamped at Dogwood Gap, a few

miles above us, while a portion of his force holds the Hawk's Nest below us.

I think the public and all military men will agree that both our fight and our fall back to this side of the river are among the most remarkable incidents in the history of war. --Seventeen hundred men, with six inferior pieces of artillery, fought back four times their number, with much superior artillery, for more than four long hours, repulsed them three times, and remained masters of the ground. They then retired, their numbers, baggage, stores, and more than 200 sick and wounded, across the river, from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m., along one of the steepest and worst single-track roads that ever horse's hoof trod or man ever saw. 4 o'clock found these men three miles from the enemy, with our newly-constructed bridge destroyed and our boats sunk behind us. I think these facts show a generalship seldom exhibited anywhere.

To read a Federal perspective of Carnifex Ferry, please check out "The 13th Ohio and the School of the Soldier."

Source:

Letter from Major Robert Henry Glass, Southern Advertiser (Alabama),

October 9, 1861, pg. 1 (originally published in Lynchburg Republican)

Comments

Post a Comment