The 51st Alabama Partisan Rangers and the Ride Around Rosecrans

Around dawn

on December 30, 1862, General Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry brigade fell upon a

Federal wagon train along the Jefferson Pike not far from LaVergne, Tennessee. Private

William C. Dodson of Co. G, 51st Alabama Partisan Rangers recalled the chaos of the scene as Wheeler’s men put the

wagons to the torch.

“Prisoners running this way and that, hunting somebody to

surrender to, army wagons blazing, guns opposing, mules braying, etc. Some of

the wagons were loaded with ammunition and some were set fire to while the

teams of 4-6 mules were yet hitched to them, and as the fire commenced to

scorch the wheelers and the ammunition to explode, you can imagine about as wild

a stampede as you can conceive of. When I first rode into the circus, I noticed

a pair of miles that had broken loose from a wagon. They were still hitched to

the double-tree; one had got entangled with the harness and was down with the

other dragging him. As I rode out, I encountered the same pair of miles, one

having dragged the other nearly a mile,” he wrote.

Private Dodson’s reminiscences of Wheeler’s first raid during the Stones River campaign first saw publication in the May 5, 1898, edition of the Atlanta Journal.

In response to your request for some

reminiscences of General Wheeler, my old commander, I will say that I was captured

in 1863 just preceding the Battle of Chickamauga so I cannot tell

you from personal knowledge anything of his campaigns after that date. However,

I was with General Wheeler before and after the Battle of Murfreesboro, it has occurred to me that possibly some of his doings during that

memorable engagement might be of some interest to your readers. Of course, the

recollections of a private must be more personal than historical and I trust I

will not be accused of egotism if I am compelled to use the pronoun “I” rather

frequently.

The Battle of Murfreesboro has always

seemed to me the most deliberately planned of any during the war and should

have resulted in a greater victory than we achieved. General Bragg seemed to

have selected his own ground, entrenched himself, and then sent his cavalry

under General Wheeler to bring on the engagement. We skirmished with the

Federals for several days, gradually falling back and “tolling” them on to the

battleground already selected. Toward the last the enemy “tolled” rather too

freely for comfort and on the afternoon before the battle we were glad to

gallop through the infantry lines to escape a shower of bullets.

The night preceding the battle we were

marched a little distance from Murfreesboro and encamped. We were allowed to

feed our horses, snatched a bite to eat and a little rest for ourselves, but no

saddles were removed and profound silence was commanded. At about midnight, we

were mounted and on the march, but what our destination was we had not the

slightest idea. The campfires of the enemy were in plain view and it seemed

that we were marching directly toward them. I remember thinking that if we were

to charge the enemy’s line what a mess we would make of it in the darkness not

being able to distinguish a Yankee from a Rebel. In fact, it was the darkest

night I remember before or since. We literally could scarcely see our hands

before our faces. We forded Stones River and I could not see the water but

could hear it gurgling and hissing and could feel it halfway up my horse’s

sides. We rode on during the night and as day began to dawn, I commenced

looking for some landmark to indicate where we were. Imagine my amazement when

I discovered we were in the outskirts of LaVergne which I knew to be 15 miles in

the rear of the Federal army.

Our regiment (Colonel John T. Morgan’s

51st Alabama Partisan Rangers) rode second in the command and it was

not long before we heard music ahead. Any old soldier will know that by music I

mean the clatter of musketry, punctured with an occasional boom of cannon.

Presently a courier came back to order up another regiment, which was ours, and

we went in with a whoop. The fighting was about over for there was but a small

force to oppose us which we brushed away with scarcely a halt. But the fun had

just commenced.

|

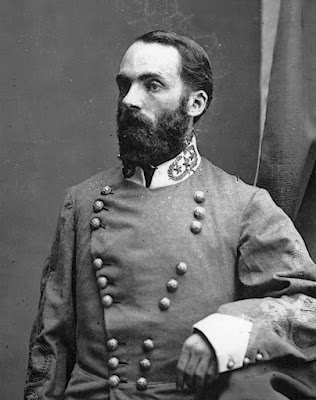

| Colonel William S. Hawkins served on Wheeler's staff during the raid and one Federal recalls that Hawkins was the officer who administered the battlefield paroles to the prisoners. |

Prisoners running this way and that,

hunting somebody to surrender to, army wagons blazing, guns opposing, mules

braying, etc. Some of the wagons were loaded with ammunition and some were set

fire to while the teams of 4-6 mules were yet hitched to them, and as the fire

commenced to scorch the wheelers and the ammunition to explode, you can imagine

about as wild a stampede as you can conceive of. When I first rode into the circus,

I noticed a pair of miles that had broken loose from a wagon. They were still

hitched to the double-tree; one had got entangled with the harness and was down

with the other dragging him. As I rode out, I encountered the same pair of

miles, one having dragged the other nearly a mile. One of dismounted and cut

the ham strings when muley jumped up as nimbly as if he had just been taking

that sort of ride for his health and was not in the least injured.

I was riding a borrowed horse and my

first care was to provide one of my own at Uncle Sam’s expense. This I did, got

him safely to camp, and rode him to the end which came for me less than a year

after. Our orderly sergeant captured the finest mule I have ever seen, a

magnificent iron gray about 16 hands high and beautifully proportioned. He was

naturally very proud of his capture until someone yelled, “Tom, look at your

mule’s eyes.” One glance and he dropped the halter like it was hot- the mule

was blind as a bat!

Of course, we were not there to stay

as our position within a few miles of an army of 15,000 infantry was not one to

hold. So we collected our prisoners and rode on to safe quarters. During

this battle, General Wheeler’s command made two complete circuits around the

rear of the Federal army, and partially a third which was not altogether

successful as the Yankees had prepared for us and we were repulsed. [See "A Gallant Defense: The 1st Michigan Engineers and the Fight for LaVergne."]

I was also with the second raid in

which we lost some men but captured more prisoners than at the first. I started

with the third raid but was compelled to return on account of a lame horse- the

third that I had rode down in that campaign for Wheeler’s “critter company”

didn’t know much about walking horses in those days, a gallop being our usual

gait. On the second raid, among the prisoners was a fellow we had mounted on an

old gray mare which had belonged to one of our company who had been killed in

the melee. She was a very rough-gaited critter and while the other horses were

in an easy lope, the old mare was in a long swinging trot and the poor Yankee

with his feet out of the stirrups clinging for dear life to the saddle and

bouncing about 6 inches from his seat at every jump the old mare made was

ridiculous in the extreme. I rode up by his side and remarked, “My friend, it

seems you are not accustomed to riding.” The poor fellow replied between gasps,

“Yes, I’ve rode in a buggy and in a carriage but never rode like this.”

It is not safe to trust memory after

all these years but my recollection is that the results of this campaign of

General Wheeler’s were the destruction of 1,010 wagons and contents, nearly a

thousand prisoners, remounting many of his men who needed fresh horses, and the

capture and destruction of a gunboat on the Cumberland River. We had the whole

Federal army without rations for nearly three days. There was a citizen of

Atlanta who was a paymaster in the Federal army and one day he remarked to me

that at the Battle of Stones River he had $100,000 in his safe and couldn’t buy

a pone of cornbread. Of course, I reminded him that I was one of the boys who

had helped destroy his rations!

As I said before, I can tell but little about General Wheeler’s subsequent campaigns but the above is a fair sample. To me, he was and is the ideal cavalry commander and I cannot help feeling personal pride in the fact that my old commander is one of the first for Uncle Sam to call into service. In my youthful eyes, such men as Wheeler, Stuart, and Wade Hampton “seemed giants and manhood’s more discriminating gaze see them undiminished.” General Wheeler never asked his men to go where he would not lead and for this, we loved him and gladly rode with him into places where we knew all could not come out alive.

Source:

“Soldiering with Wheeler on Murfreesboro Field,” Private William Cary Dodson, Co. G, 51st Alabama Partisan Rangers, Atlanta Journal (Georgia), May 5, 1898, pg. 8

To learn more about the Battle of Stones River, be sure to purchase a copy of my campaign study Hell by the Acre, recently awarded the Richard B. Harwell Award from the Atlanta Civil War Roundtable as best Civil War book of 2024. Available now through Savas Beatie.

Comments

Post a Comment