A Harvest of Blood: Exploring the field after Shiloh

A special

correspondent of the Philadelphia Daily Inquirer following in the wake

of the Union army entered the shattered debris of Sarah Bell’s peach orchard

and cotton field on the late afternoon of Monday, April 7, 1862 intent on

exploring the field. The sights, smells, and sounds staggered the reporter:

arrayed before him were hundreds of dead and wounded soldiers, blue and gray,

surrounded by the scattered refuse of war: discarded and battered rifles, ripped

and torn clothing, bullets and cannon ball fragments, broken swords revolvers,

and everywhere blood.

“In one place lay nine men, four or five of ours and about as many Rebels who from indications must have had a hand-to-hand fight. They were all dead and bore wounds evidently made with bayonets and bullets. Two of them had hold of another’s hair and others were clenched in a variety of ways,” he recorded. “One seemed to have had a grip on the throat of his antagonist and been compelled to relinquish it judging from the frigid marks. The most singular attitude of any I have ever observed was that of one Union soldier the position of whose body was similar to that of a boy’s when he is playing leapfrog.”

“While

surveying the killed and wounded in a large wooded locality where trunks of

large trees lay about in a half-rotten state, I stepped upon on to look about

the ground and hearing something move at my feet, I looked down upon was

evidently the figure of a man covered up by a blanket and lying close up

alongside the log. The ground was thickly strewn about him with bodies, many of

whom I found to be only wounded. Lifting the blanket from the man’s face as I

dismounted from the log, he immediately faltered out, ‘Oh sir, I’m wounded, don’t

hurt me. My leg is broken and I’m so cold and wet.”

“Within

three feet of this wounded secessionist lay a dead Union soldier with his hair

and whiskers burned off. I soon learned that the leaves and dead undergrowth

had been fired in various places by the explosion of shells and also be burning

wads, the fires communicating to the bodies, burning them shockingly. Some of

the wounded must have been burned to death as I observed one or two lying upon

their backs with the hands crossed before the face, as a person naturally does

when smoke or heat becomes annoying.”

“Replacing

the blanket over the face of the wounded man, I proceeded to step over another

log nearby and was considerably startled by a loud exclamation of pain from

another wounded Rebel. Having stepped on a small stick that hurt his wounded

limb by its sudden movement, he was compelled to cry out. He was snugly laid up

close alongside a fallen tree. His wound was serious and the poor man begged

for some assistance. The only thing I could do was to get him a little water

and promise that somebody would soon come to his relief. “What will you do with

us?” the wounded man asked me. “Take you, dress your wounds, give you plenty to

eat, and in all probability when you are able, require you to take the oath of

allegiance and then send you home to your family if you have one.”

“The appearance of the dead on the field was rather singular. In one place lay five men who appeared to have sheltered themselves behind a tree in order to take better aim at our men. A shell had burst just over their heads. One man was struck just on the top of the head, another on the side of the head, and each consecutive man was struck lower down about the breast and body in regular order. One of the men grasped in one hand a musket with his cartridge in the other just in the act of pouring the powder in; another was ramming the cartridge and the other men engaged in similar occupations when the fatal shell burst. In another place I saw a man with a hole in his hand as large as your hand through which his brains had run all out leaving his skull entirely empty. As I passed over the field, I observed a cannon ball lying on the ground. I picked it up and it was covered with the blood, hair, and brains of some poor fellow. I tell you I dropped it suddenly.” ~ Quartermaster Lorenzo S. Myers, 64th Ohio Volunteer Infantry

“There

was an old man, his locks sprinkled with gray, kneeling beside a stump as if in

attitude of prayer, his face now resting in his hands, and head reclining on the

top, apparently having gone to sleep in death while in the act of devotion. A

ghastly wound in the side told of his end. Another powerful looking man had

just placed a cartridge in the muzzle of his gun and had the ramrod in his

right hand as if about to ram it down. Death caught him in that moment and as

he lay with upturned face, the left hand clenched the gun and the right one the

ramrod. One soldier loaded his piece and paused to take a chew of tobacco.

Beside his body lay the gun and in his right hand was the flat plug of tobacco

bearing the imprint of teeth. Some had lain down quietly with their heads

resting against a stump or tree, their caps resting on their faces, and had

thus died alone and unattended. Yet the calmness and repose of the countenance

as one raised the covering indicated a peaceful departure to the spirit world.

Death caused by a bullet leaves a quiet, calm look behind while a bursting

shell, bayonet, or sword carry with them a horror that remains depicted in

death.”

|

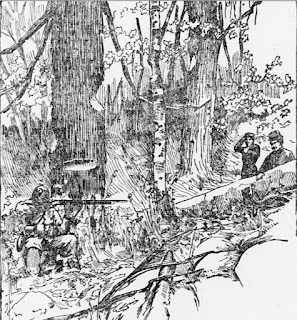

| Two Union soldiers examine a dead Confederate soldier shot dead in the act of firing his rifle at Shiloh. |

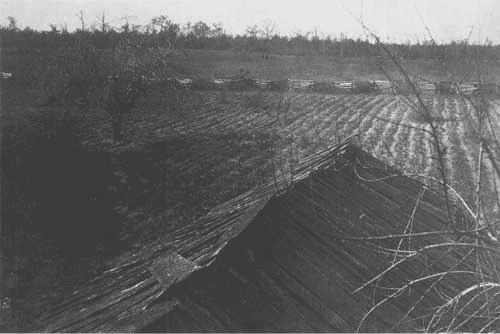

“It was

an excellent time to choose a gun: there were Harper’s Ferry rifles of both the

old and new pattern, Springfield rifles with Maynard primers and without, the “Tower”

Enfield rifles, Mississippi rifles, double and single barrel shotguns, rifles

bearing the Palmetto stamp and made at Columbia, S.C. and Fayetteville, N.C.

Swords of various patterns reeking with blood, broken and bent scabbards,

partially-discharged revolvers, and military trappings in such an endless

variety that to have possessed them would have been the fortune of any

individual. In the clear field fronting the peach orchard, a variety of bullets

might have been gathered as they were lying about on the ground like fruit from

a heavily-laden tree after a storm…”

Sources:

“Battle

Field of Shiloh,” Altoona Tribune (Pennsylvania), May 1, 1862, pg. 2

Letter

from Quartermaster Lorenzo D. Myers, 64th Ohio Volunteer Infantry,

Mahoning Register (Ohio), April 24, 1862, pg. 2

Comments

Post a Comment