Braxton Bragg and the Tupelo Revival

At the end of May 1862, the Army

of Mississippi abandoned its positions surrounding Corinth, Mississippi and

conducted a 50-mile march to go into camp near Tupelo. The army was in ragged

condition: a field return from June 9, 1862 shows that of the total force of

94,756 officers and men on the rolls of the army, only 45,335 were in condition

for duty. As a matter of fact, nearly a quarter of the army was sick either in

the hospitals or absent from the army. The poor health conditions at Corinth

contributed to widespread demoralization and by the time the army marched into

Tupelo, one veteran noted that “it was a perfect rabble that would have done

much more running than fighting if they had been put to the scratch.”

Sickness

was no respecter of rank, and in this case the commander of the army General Pierre G.T.

Beauregard was just as sick as his many of his men. The Creole had been

battling poor health for months and the strain of assuming command of the army

in the wake of General Albert Sidney Johnston’s death at Shiloh exacerbated the

severity of his condition. By mid-June, Beauregard was completely wiped out and

“after delaying as long as possible to obey the oft-repeated recommendations of

my physicians to take some rest for the restoration of my health” Beauregard

left the army in command of General Braxton Bragg and set out for a rest cure

at Bladon Springs, Alabama. Beauregard’s action, taken without the consent of his

superiors, led to his prompt removal from command and made Bragg’s temporary

appointment a permanent one.

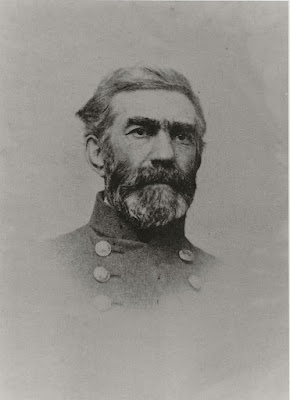

Bragg

inherited an army in shambles, “one great tangle of difficulties” as remembered

by historian Stanley Horn. The men had shown that they could fight, but known

nothing but defeat, retreat, and suffering since the start of the year. Morale

was low, sickness and desertion widespread, and the men were indifferently

armed and poorly equipped. The impact of the Conscription Act and reorganization

of the army’s regiments had further eroded morale and presented the new

commanding general with a set of problems as impenetrable as a briar thicket. As

Bragg complained in a letter to his wife, this wasn’t an army, it was a mob. Regardless,

the command was now his and Bragg went to work with a will to turn things

around.

Fortunately

for the army, General Henry W. Halleck did Bragg a solid favor by giving him

the dual gifts of time and space. Despite amassing an army of 125,000 men

around Corinth, Halleck chose not to pursue his Confederate opponents when they

marched for Tupelo. “Old Brains,” always consumed with logistics and with an

eye on future promotion, elected to spread his army out across the region and focus

on pacifying the population while repairing the railroads to ensure a steady

supply during the dry months of the summer. Logistically, it may have been the

right move, but it took the pressure off the Army of Mississippi and granted

the army a lengthy respite that Bragg put to good use.

First

and foremost, efforts were made to improve the health and well-being of the

men. Getting out of the unhealthy environs of Corinth proved a tremendous boon

in itself, and army’s camps at Tupelo were located on sandy ridges “covered

with a growth of oak, black-jack, and hickory,” recalled Colonel William P.

Johnston. “The position is healthy, pleasant and capable of defense.” The men spread

their tents among the shade of the trees and set to work digging wells. One

veteran remembered that the wells were “about 25 feet deep with a sugar hogshead

on the bottom with the tops surrounded and covered by rails.” Located along the

Mobile & Ohio Railroad, the supply situation started to improve and soon

the men were enjoying increased rations, particularly of beef which was issued

five days per week and corn meal in lieu of flour. “The soldiers prefer corn

meal to flour,” Colonel Johnston noted and while he observed that most of the

men were poor cooks, they were learning from experience.

The

next order of business was to instill Bragg’s own brand of discipline on the “mob.”

He cut his inspectors loose and shook up the army from stem to stern. Bragg

insisted on a strict observance of military law and customs, punished deserters

with public executions, and set the army to work learning to be soldiers. Lieutenant

Colonel Camille de Polignac, one of Bragg’s inspectors, wrote that “the men

have been accustomed for years to have no check put on their proclivities.

Evils in this army have to be corrected partly by persuasion, partly by

compulsion.” It was once a common

occurrence to hear the discharge of firearms within camp at all hours of the

day, but Bragg clamped down hard on that, even having a man shot for

discharging his weapon without orders. “Since that time, the discipline of the

troops was improved very much,” John Buie of the 23rd Mississippi

wrote. “Men are not apt to disobey orders when they know that death is the

punishment.” “We are going to have no more playing soldier in General Bragg’s

army,” one officer commented. These strong measures are the only ones that will

do the army any good.”

Earlier

that spring, the Confederate Congress had inadvertently added to General Bragg’s

command woes by passing the Conscription Act, a necessary but wildly unpopular

measure that extended the term of service of every soldier in the army to the

duration of the war. It also forced each regiment to reorganize along with new

elections for officers; the measure led to the election of many officers that

Bragg found totally unfit to command and had to remove via boards of

examination. “The elective feature of the conscript law has driven from the

service the best who remained and to a great extent demoralized the troops,”

Bragg complained. William Watson of the 3rd Louisiana remembered

that one Tennessee regiment who insisted on their right to go home at the end

of their term of service “laid down their arms and refused duty. Bragg then

brought up a strong force and surrounded them, and then directed a battery of

artillery against them and gave them five minutes to take up their arms. The

men sullenly obeyed, each muttering to himself that it would be but little

service he would ever get out of them. A good many deserted but some were

caught attempting to desert and were summarily executed without any trial.”

Roughly

3% of the army were listed as deserters and as the men were caught, Bragg

resolved to make an example of them. The first one executed was a solider in

the 7th Arkansas was refused to do any duty of any kind, essentially

a mutineer. On June 17th, the man was shot in front of his brigade. “Our

whole brigade was ordered out to see the execution,” stated Lieutenant Frank

Denton of the 8th Arkansas. “I saw him shot when the ball struck

him. The men were very clamorous about going home when their time is out until

this youth was shot. Now they are taking it easy.” Sam Watkins of the 1st

Tennessee recalled that two soldiers from the 23rd Tennessee

received a public whipping and provided a graphic description of the

proceedings. “The man who did the whipping had a thick piece of sole leather

the end of which was cut into three strips and this tacked to the end of a

paddle. The whipper let in. I do not think he intended to hit as hard as he

did, but being excited himself, he blistered Rube from head to foot. When he

struck at all, one lick would make three whelps.”

Bragg

worked incessantly at Tupelo to obtain new clothing for his men since so much

had been lost during the previous two months of active campaigning. “Our

regiment as gone to nothing,” complained one soldier in the 14th Arkansas.

“Our report to General Hebert this morning was 225 men in all, 82 without

shirts, 96 without shoes, and 38 without hats.” Bragg secured 140 boxes of

newly made clothing from the Columbus, Georgia depot in early July and

distributed it amongst him troops. “Goods uniforms add immensely to the make

and esprit de corps of soldiers,” noted the Mobile Advertiser & Register.

“A good bath and a clean shirt raises every man in his self-respect and is the

basis of all virtues, heroic and civil. If the Confederate troops had been disciplined,

armed, and equipped like those of the Yankees, they would have been waving the

Bonnie Blue flag in Boston before now.”

Another

article required by the army was wagons- to sustain an active campaign, the

Army of Mississippi needed a much larger fleet of wagons to haul supplies, but

since the Confederate government wasn’t able to furnish them, Bragg’s army was

forced to “impress” them from the civil populace. “We were often compelled to

take such articles wherever they could be found without regard to the wishes or

desires of the possessors,” Quartermaster Silas Grisamore of the 18th

Louisiana stated. “It was always an unpleasant business.”

Drill,

the bane of a soldier’s existence, became a constant feature of the camp at

Tupelo. Bragg, operating under the credo that a busy crew is a happy crew, ordered

that five hours a day six days a week, the new soldiers and the veterans went

through the monotonous exercise of the manual of arms, company drill, and

battalion drill. John Jackman of the 9th

Kentucky commented that “or battalion drill at 2 p.m. was hot work. All the

while encamped at Tupelo, we had regular drills and the weather could not have

been hotter.” It was hard and grueling work, but an essential element in

hardening the troops for the challenges and hardships of the upcoming campaign.

And the impact on the vigor of the army quickly drew notice. “Instead of a pale

face, feeble gait, and dejected appearances of the invalid, I met with the

clear complexion, elastic step, and cheerful countenance which betokens health

and vigor,” Corporal Benjamin W.L. Butt observed in July. “Our army is

recruiting so fast that it will not long remain inactive.”

Most of

Bragg’s efforts to improve the discipline of his army met with scarcely feigned

disgust from his men, and the stridency with which his measures were adopted

led some to view Bragg as “a merciless tyrant. He loved to crush the spirit of

his men. The more of a hang-dog look they had about them, the better,”

complained Sam Watkins. General Alexander P. Stewart averred that Bragg was an

able officer but “he did not win the love and confidence of either the officers

or the men.” Stanley Horn commented that “despite its antagonistic attitude

towards its commander, the army at Tupelo…was ready to take the field.”

But

by late July when Bragg put the army on the move to Chattanooga, it hardly resembled

the rag-tag force that marched into Tupelo a month earlier. In a word, the army had been revived. The Bragg touch,

rough-hewn, severe, and harsh as it was, turned the army into a well-crafted

instrument of war. More importantly, the army began to believe in itself again.

“There has been a marvelous change for the better in condition, health,

discipline, and drill of the troops since this army left Corinth,” one officer

noted with pride. Another soldier noted that “the troops are all in fine

spirits and seemed perfectly willing to fight on till the last invader is driven

from Southern soil. When our boys breathe the fresh mountain air of Tennessee,

they will soon be prepared to ensure every toil and danger incident to the long

fatiguing marches they will be called on to make in the campaign before them.”

Source:

Masters, Daniel A. Adrift in a Sea of Blood: A Narrative History of the Stones River Campaign. Savas Beatie, 2024

What is surprising is how many men Johnston had executed in 1864, and yet the men remembered him fondly. What a difference two years made.

ReplyDeleteReally, wasn't aware of this, about how many did Gen. Johnston execute?

Delete