The Sterner Realties of a Soldier’s Life: Charles W. Evers of the 2nd Kentucky at Shiloh

The son of a cabinet maker, Charles W. Evers was born in Miltonville, Ohio on July 22, 1837 and grew up in the wilds of Wood County. By the time he reached his maturity was teaching the local district schools. At the age of 19, he struck out for the West and spent a few years on the Minnesota frontier before returning to Ohio in 1860 to study at Oberlin College with his older brother John. The outbreak of war led the two brothers into different theaters of war: John enlisted with many of his Oberlin classmates in Co. C of the 7th Ohio Infantry (see here) and went east to Virginia while Charles enlisted in Co. H of the 2nd Kentucky Volunteer Infantry and served in the western theater. A younger brother Orlando later served in the 67th Ohio in the eastern theater (see here).

Despite its Kentucky moniker, the ranks of the 2nd Kentucky were composed almost entirely of Buckeyes. The regiment first saw service in the western Virginia campaign of the summer of 1861 taking part in several small scale engagements before being ordered to Kentucky to join the western army in February 1862. The regiment was assigned to General Don Carlos Buell's Army of Ohio and served with that army and its successors for the remainder of its service, winning distinction at fields such as Shiloh, Stones River, and Chickamauga. Charles Evers always took pride that he "never missed a march or battle that his regiment was in" until he was severely wounded and captured September 19, 1863 at the Battle of Chickamauga. Charles remained a Confederate prisoner for roughly two months before being exchanged and arrived at Camp Parole in Annapolis, Maryland just in time to save his badly mangled leg. Charles survived, but the experience ended his service with the army and he was mustered out in June 1864.

After the war, Charles Evers returned home to Wood County, Ohio and was elected to a two terms as county sheriff starting in 1865. In the early 1870s, he became editor of the Bowling Green Sentinel newspaper and worked diligently to build up the paper until the mid-1880s when he retired to his farm and business interests. Always fascinated with history, Evers devoted the remainder of his life to documenting the stories of pioneer life in Wood County, writing the county history in 1897 and Reminiscences of Pioneer Days in Wood County and the Maumee Valley before his death in 1909.

Headquarters, 2nd

Kentucky Regiment, 22nd Brigade, Division of General Nelson

Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee

April 17, 1862

I

take pleasure in laying before your many readers that portion of my daily

journal relating to recent events which will perhaps vary the monotonous

history of camp life to something of a more stirring nature. I am fully aware

of the impatient anxiety of your peaceable communities at home to hear of the

splendid military achievements and masterly military feats from the mighty army

which they have equipped and sent forth at so great a sacrifice and expense; also,

of the difficulty public journals find in staying the hurried expectations of

the people. But despite all sensational reports that can be manufactured, each

great event must abide its time. Hence the long quiet just broken.

The

fall of Donelson and the evacuation of those strongholds Bowling Green and

Columbus and the hasty retreat of the army southward, hardly pausing at the

Tennessee capital, evidently changed the plans of the campaign to a small

extent as he had thought no doubt to present a strong line of defense from the

Cumberland Gap to Columbus on the Mississippi River, but the fall of Donelson

and its succeeding advantages to the Northern army was a disheartening blow for

his whole line, as if cut loose from its anchor, drifted southward followed by

the now gathering forces of the North.

Nashville

now appeared to be the chief point of accumulation both in point of convenience

and strategy, it being rather a central position and noted for the disloyalty

of its citizens, for from the delicate female to the most daring patriarch

father of their miserable dogma came the vilest reproaches and epithets on the

heads of the “hireling Yankees.” Nor do I care to obscure the fact, though I

may differ with many in regard to this matter, but that the people of the North

should clearly understand to what extent the Union sentiment prevails appears

to me to be both proper and politic; there are portions of the state of

Tennessee that are largely Unionist, but we rarely find such here. (see story of Federal occupation of Nashville here)

It

was at Nashville that I first became alive to the vastness and magnitude of

Uncle Sam’s forces. The city appeared like the metropolis of some great warlike

nation whose whole occupation and resources were the pursuits of war, and that,

too, on a large scale. At least they were in great contrast with the mountain

forces of Virginia of which have previously been a part. Battalions were

marching through the streets with colors flying and martial music playing while

the sidewalks and pavements were thronged with scattering soldiers and gazing

civilians. Windows were crowded and mother, who fancied they now actually

beheld that dreaded animal “the live Yankee” armed to the teeth and bearing

death and destruction to some misguided husband, brother, or lover in Dixie. I

thought within myself, this is a military age surely, and that the present era

would chronicle great events on the pages of modern history. The boat landing

was crowded with thousands of spectators, teamsters, mules, horses, batteries

of artillery, mounted cavalrymen, and field officers, all riding to and fro,

and even the river itself was occupied by that dangerous looking craft the

gunboat Pittsburgh with her low stature, black uniform, and immense

Parrott guns seemed to be enjoyed a sullen supremacy over the different crafts

of her own tribe which hovered nigh.

|

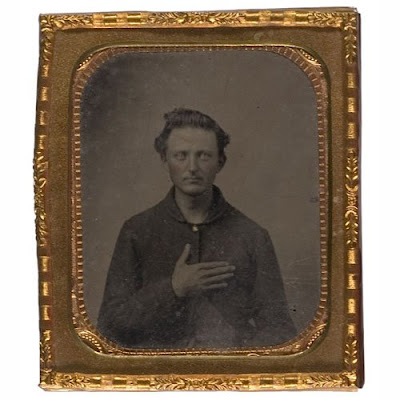

| Private Amos Hussey of Co. F of the 2nd Kentucky joined the regiment in January 1862 and was wounded the same day as Charles Evers and likewise survived the war. |

The

adjoining plain was a complete city of tents and the roads thereto were

thronged with soldiers and trains. Here we camped until March 17th

when our whole division broke up camp and marched for Savannah to join the

forces of General Grant which were passing up the Tennessee River. As far as

the eye could reach to the front or rear could be seen only the bright gleam of

muskets and the thousands of shiny knapsacks which crowded together and with

the continual motion from one side of the wide road to the other gave the scene

an appearance not unlike the dark undulating swell of some bold deep river. Our

line of march was not marked by anything particularly noteworthy. The divisions

of Generals McCook, Thomas, and Crittenden marched by the same route as we did,

General Mitchel taking the Murfreesboro road towards Huntsville, Alabama.

At

the town of Columbia on the Duck River, we met as we had done at almost every

stream one of the enemy’s greatest defenses- a burned bridge. General McCook

halted his column to complete the bridge which was partly rebuilt. General

Nelson, whose division came next, impatient to advance, ordered his men to take

their clothes and ford the river, which we did and that evening we camped on

the plantation of the Rebel General Gideon Pillow. Good orchards, fences, and

well-arranged fields and buildings displayed alike good taste and industry. I

am reliably informed that this Rebel gained this fine property while in the

employ of that same government he now seeks to overthrow. May he not escape the

frowns of Heaven…

Affluence

and plenty were the universal characteristics everywhere seen. Large stately

farmhouses of modern architecture, some of Oriental style and taste, finely

decorated yards, good fences, well-hung gates, fine springs of water, and to

render the scene still more pleasing, spring had now begun to shed her gentle

breezes upon all nature. The peach and plum trees were all in bloom and the

balmy fragrance of thousands of spring flowers cheered the weary soldiers’

march. The banks of the numerous rivers and creeks were gorgeously decorated

with the mingled blossoms of the red bud and dogwood trees, largely interspersed

with the dark green foliage of the evergreen among which sported numerous birds

peculiar to southern climes. But I must pass on to the sterner realities of a

soldier’s life.

On

Friday April 4th a heavy wagon guard was detailed commanded by a

major to stay with the division commissary train of 140 loaded wagons and guard

them to Savannah now 24 miles distant over bad roads. I was one of the party

and late on the evening of the 5th we had almost despaired of

getting through when within four miles of the place, but an express order from

General Nelson to come in if it killed every mule again brought forth all the

ingenuity and patience of the teamsters which together with sundry kicks,

curses, whacks, and thumps from the impatient guards frightened the poor, jaded

mules into renewed exertions and we arrived within two miles of the place

battered up, hungry, weary, and not the least vainglorious of the new title of

M.D. (mule drivers) which we had now acquired.

After

passing the night in the open air, I woke in the morning with a glorious Sabbath

sun shining full in my face. I now heard the distant firing of cannon which I

could not account for as Beauregard was supposed to be at Corinth 18 miles

distant, but a field officer soon arrived with orders to join our regiments

immediately. The firing now grew louder, nearer, and faster, and we hardly got

into camp when news came that the enemy had attacked Grant’s men, taken one

brigade prisoners, and for us to strike tents. In a very short time, we were

all ready and in line. The distance to Pittsburg Landing where the firing was

is about nine miles which we made in both quick and double-quick time, taking

the shortest route which led through a low swampy tract of country, but we

heeded not road or swamp as a matter of greater import was ahead.

The

roar of artillery grew plainer every moment and the ever-beating echoes

thundered through the heavy-timbered bottoms like the roar of some great

cataract. We now emerged into a large open field which bordered upon the river

and from which a full view of the landing was open to us. The opposite side of

the river, a gradual rising bluff, was crowded with soldiers, teamsters, mules,

and wagons, all appearing in agitation and confusion. The soldiers without

guns, many of them were skulking and dodging about with their backs to the

approaching enemy. Here then was the material for a regular Bull Run stampede

with affrighted stragglers, teamsters, and mules (no Congressman); a fortunate thing

it was that the river held them in check. In the river lay about a dozen

transports with the gunboats Tyler and Lexington (see story here) which was now the

chief obstacle to the advance of the enemy now within 500 yards of the river.

The Rebels had captured ten batteries and three regiments together with General

Prentiss and occupied about two-thirds of our camp- indeed, so confident were

the Rebel commanders of success that they ordered none of the Federal property

to be destroyed.

Such

was the critical condition of affairs when General Nelson’s advance guard

appeared on the opposite side of the Tennessee River. Blucher’s arrival at

Waterloo could not have been more timely. We were now drawn up in line in the

open field. The sun was now nearly setting, a long line of low broke fiery red

clouds set in a lake of deep azure blue fringed the western horizon while on

the east the sun’s long bright halos were reflecting on the dense forest trees

whose silvery buds were now fast putting forth, assuming a bright scarlet

uniform of a grand and imposing appearance.

But

in less time than I am writing, General Nelson pushed his column across the

river, the 19th Brigade charging bayonets upon the enemy, driving them

back from their advanced position. We formed in line of battle where we lay all

night with loaded guns amid the drenching showers of rain. At daybreak in the

morning, two parties of skirmishers were thrown out and the whole of General

Nelson’s division which formed the left wing advanced in line. The skirmishers

fell in with the enemy’s pickets in the outskirts of the Federal camp where

they had been in the shelter of our tents during the night but left now upon

the shortest notice and joined the main line. I shall now continue myself

mostly to my own regiment whose position lay near the extreme left.

A

sharp firing now commenced on our right, but the line still advanced when quite

unexpectedly a battery opened directly in our front and close by which annoyed

us very much. The 1st and 20th Kentucky were now engaged

briskly- the battery throwing grape and shell in all directions. Our

skirmishers now made a charge on the guns and captured them, but another now

opened on the right with a galling fire which was only answered by some

sharpshooters sheltered in a clump of trees. Terrill’s battery (see story here)

was now ordered up and a sharp artillery fight began which lasted until about 8

o’clock on account of their battery being strongly protected by infantry which

was ambushed behind logs, trees, and bushes and kept up a galling fire on the 1st

and 6th Kentucky. But the Rebels evidently found a different class

of men from those they met on the previous day, the Kentuckians not giving an

inch.

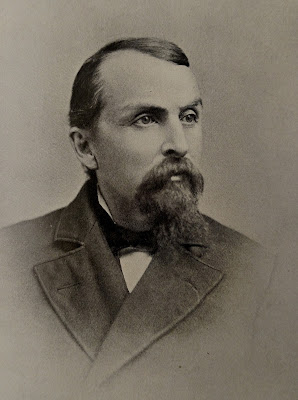

|

| "Our gruff old General" General William Nelson |

Our

gruff old General, who was galloping over the field the whole time and upon

whose shoulders more than any other men rested the fortunes of the day, now

rode up and said, “Colonel Sedgwick, that battery must be taken! Charge on it

immediately! Unsling knapsacks! Forward, quick time!” And at them we went. They

were ready for us and when within 100 yards of the battery, we got their full

fire of grape, shot, and shell, Minie balls, and Rebel coats combined with

thunder and lightning seemed to have risen out of the ground. This seemed to be

the signal for a general attack. The thunder of artillery would be heard along

the whole line from right to left. The whole woods and brush seemed a glare with

one continual blaze. Within 30 yards where at first nothing could be seen now

appeared almost a solid phalanx of butternut jackets. The Kentuckians were at

first staggered but put in their fire with a telling effect, and as we poured

in volley after volley and the Rebels saw no signs of our falling back, they

hastily betook themselves to the tall brush and rallied on their battery further

to the left.

They

made a desperate charge on the 2nd Kentucky and but for the brave 14th

Wisconsin and 6th Kentucky, we would have been overpowered and cut

to pieces. They now fell back, leaving the ground strewn with their dead and

wounded but before we had got hardly reformed into line and other troops

brought to our assistance, they had rallied and brought in a heavy force

farther to our left, no doubt with the intention of breaking through our lines

and flanking three or four regiments stationed on the left. This was about 1

p.m., the turning point of the day, and perhaps the most terrific and obstinate

onslaught during the battle. The brunt of the charge fell wholly on Nelson’s

troops. The center began to waver and give way, the Wisconsin boys fighting

like tigers. I saw captains and lieutenants of the 14th with hat in

one hand, swords waving over their heads swearing and foaming and calling their

men after them to death or victory, while balls were cutting off almost every

shrub or bush on the ground. The enemy’s forces seemed to be strengthening and

gaining ground on us in defiance of the bold stand we made.

At this

crisis, a loud cheering was heard to the rear and looking across a cotton field

we saw the gallant [Alexander M.] McCook, who had just arrived, filing over the

fields to the left. In a few moments the battle raged with redoubled fury, the

Rebels fired to madness with whisky which had been furnished them for the occasion,

contested every inch of ground and when forced to fall back, would rally again,

and renew the charge with double fury. The roar of artillery was now terrific,

no thunder that I ever heard could equal it. Large trees were cut entirely off.

The birds and smaller animals were stunned so that you could take them in your

hands without their making any effort to get away. No one can form an idea of

the effects of such firing until actually in it; my ears were deafened, and I

have not gotten over the effects even yet.

|

| General Alexander M. McCook |

Between

3 and 4 o’clock the enemy gave way and commenced retreating with our cavalry

pursuing them until dark and taking a number of prisoners. Thus, closed one of

the bloodiest battles of the war and one which reflects credit upon the

Northern arms while it casts some blighting spurs on Southern chivalry. Had I

time and space I would relate several interesting personal incidents. At the

time I am writing, we are encamped on the battlefield, some parts of which are

sickening to behold. The enemy’s loss is much greater than ours. Of my own

company, 18 fell in the first fire, we being one of the color companies partly

accounts for the heavy loss. I sprang to a small tree after the first volley

and was joined by two of my comrades both of whom fell, the blood of one of

them spattering my face when the ball struck him. Such are a few of the

confused details made while on picket and with the close of day, I must close

this poorly written communication.

C.W. Evers

Source:

Letter from Private Charles W.

Evers, Co. H, 2nd Kentucky Volunteer Infantry (U.S.), Perrysburg

Journal (Ohio), May 14, 1862, pg. 1

Comments

Post a Comment