A Carnival of Death: A Federal Officer’s View of the Battle of Nashville

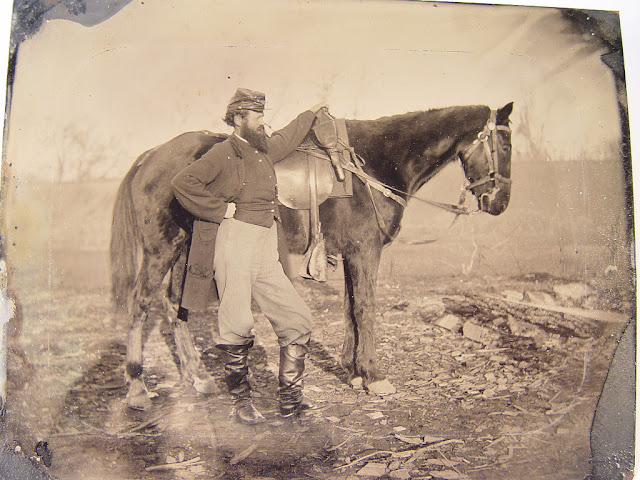

After fighting in over a dozen engagements in the past two years as a member of the 99th Ohio Infantry, Lieutenant Colonel John Cummins was no stranger to life on the battlefield. But what he saw on the first day of the Battle of Nashville took his breath away.

"A fog concealed our movements early in the morning, but it soon cleared away," he wrote to his father a week later. "The sun shone brightly and revealed the fact that the troops were moving out of Nashville on every road- cavalry, infantry, and artillery. You could see long lines like great serpents dragging their slow length along in every direction. White troops and black troops, veterans, and new recruits, all moving to the carnival of death. The inner and outer lines of breastworks were soon passed and artillery booming in our front soon informed us that the Rebels waited our coming and the contest was begun."

During the Nashville Campaign, the 99th Ohio was part of General Joseph Cooper's First Brigade of General Darius N. Couch's Second Division of the 23rd Army Corps. The 99th Ohio formerly had served in the 21st and 4th Army Corps of the Army of the Cumberland but was transferred to the 23rd Corps in June 1864 during the Atlanta campaign. Colonel Cummins' letter to his father originally saw publication in the January 6, 1865 edition of the Sidney Weekly Journal.

Headquarters, 99th Regt., O.V.I. near Duck River, Tennessee

December 22, 1864

Having time

this evening I write you. On the night of December 14th, I received

orders to be ready to match at daylight with three days’ rations in haversacks

and 60 rounds of ammunition in cartridge boxes. That I knew meant business and

brisk operations, too. At daylight, we commenced moving and I soon found we

were moving out towards Hood’s army. A fog concealed our movements early in the

morning, but it soon cleared away. The sun shone brightly and revealed the fact

that the troops were moving out of Nashville on every road- cavalry, infantry,

and artillery. You could see long lines like great serpents dragging their slow

length along in every direction. White troops and black troops, veterans, and

new recruits, all moving to the carnival of death.

The inner and

outer lines of breastworks were soon passed and artillery booming in our front

soon informed us that the Rebels waited our coming and the contest was begun.

The hustle and hurry of the approaching battle was apparent everywhere as

wherever you cast your eyes the battle lines were forming with skirmishers

thrown out then commenced moving forward. The rattle of small arms soon could

be heard, and the movements of troops became more rapid, the driving of

artillery horses more furious. A great battle was being fought. The sun shone

brightly for a time as if to lighten up and cheer the men in their death carnage,

but soon became obscured again as if frowning on what was passing below. Our

division was in a rare line and kept moving forward in line of battle through

thickets, over meadows and cornfields, over ditches and gulches, up and down

hills, passing here and there a dead or wounded Rebel or Union soldier yet

stopping not to notice them until about 2 o’clock we became the front line,

passing other troops.

On we moved

until crossing a large open field where we found the enemy in our front on a

high, rocky, steep hill and on the left flank of our brigade then ahead of our

line behind a stone wall. Musket balls flew thick on our left from the stone

fence and upon the hill in front; three pieces of artillery also opened upon us

from the hill. I saw the first smoke of the guns and said to the men ‘look out,

it is coming.’ A shell burst in front of the line and one in the rear throwing

the dirt high in the air. The men yelled and without orders jumped forward

knowing instinctively their only safety lay in running rapidly on. So they

rushed impetuously forward amid the grape and canister that the battery sent

us, crossing the field and climbing the hill in a shorter time than I can

relate it. The Rebels fled panic-stricken. Some of the horses were shot down

and the guns were captured and turned on the enemy. Our line advancing on the

left drove them from the stonewall capturing many of them. It was a rout as far

as I could see.

We followed on

capturing prisoners until we gained the top of the second hill when our line

being much broken by our rapid movements was ordered to halt and night

approaching, we went to fortifying immediately. As we were charging up the

hill, Adjutant Walkup’s horse was shot and he had to leave him- the horse

afterwards died. My horse was struck with a spent ball and rearing and

plunging, my saddle turned and unseated me in a style I don’t much fancy. As I

was among rocks, I was fortunate to escape with slight sprains and bruises. I

was soon mounted again and going up the hill at no slow pace.

I never saw men in my life so

impetuous, so eager for the strife, as all of the men of our army were on that

day. Whenever the enemy opened a battery, all that was to be done was to give

the order charge and away they went with shouts and yells determined to

succeed, and they did succeed for they captured them in every trial. Every man

appeared confident of victory, every soldier felt himself a hero and acted as a

hero should. The Rebels appeared panic-stricken and would not stand. They

appeared to have no hope of success. Never were such results achieved with so

little loss. A Rebel major of artillery said “he never saw such damned reckless

men to charge. They didn’t give me time to warm my guns!”

“A puff of smoke on a hill to our front and distant about a half a mile followed in a few seconds by the striking of a shell between our regiment and the 3rd Tennessee on our right gave us our cue. Away we went, without orders, for that hill. Through mud shoe top deep, over fences, across ditches, all organization lost before we reached the foot of the hill. As I passed a log house a charge of canister raised the shakes on its roof and the hair on my roof at the same time. It won’t lay straight yet.” ~ Private William Taylor, Co. D, 99th Ohio

We had struck the left flank of

the Rebel army and were driving them endways. On other parts of the field our

army succeeded well, yes, succeeded nobly beyond all expectations. Our regiment

only lost seven wounded on the 15th. The hills on which the Rebels

planted their artillery were so high that they could not depress their guns

sufficiently to injure us much when we charged them. At night a drizzling rain

set up and tired and weary there was no sleep for us. The line must be

fortified to guard against reverses on the morrow. We worked all night. At

times I had hard work to keep any of the men at work as they were so wearied,

and I had the officers woken up several times and required them to keep their

men at work. I slept not a wink until about daylight the next morning.

At daylight we found the enemy

entrenched on a hill in our front in easy rifle range. But they had no battery

planted and we did; it soon opened, and the second shot knocked off a head log

in one place making the Rebels scatter in a way which was quite amusing to our

men. We remained quiet in our works the greater part of the 16th,

but the fighting was brisk all day on the other parts of the line. Within sight

of us the Rebels opened batteries several times during the day, but they no

sooner opened than a charge placed them in our hands. It was amusing to hear

the men joking about the Rebel artillery. They seemed only to want them to

reveal the positions of their guns so they could capture them.

In the afternoon a brigade of

the 16th Army Corps charged on a hill in our immediate front, taking

it with ease, and our lines closing up in other directions, a large number of

Rebels were captured. We fought none on the 16th and when in the

afternoon we moved out on to the support of other troops, the rout of the

Rebels was so complete we did not come up with them. One line of our troops was

enough to drive them from every position. All the artillery the Rebels used

fell into our hands and frequently it was captured before they could get it

into position. Night saved Hood’s army from annihilation. Many of the prisoners

were jubilant at the idea of being captured as all admitted they were badly

whipped and cursed Hood for bringing them to Tennessee. Many were bare-footed

and ragged, thinly clothed, and without blankets. They had been told there were

scarcely any but new recruits and drafted men at Nashville, and they inquired

eagerly what troops ours were. They knew none but old troops could fight as our

men did, some of them thought Sherman must have come back with his men.

“The Rebel breastworks presented a sickening sight. We crossed at the point where the artillery fire was concentrated. Six Rebels were held in the trench by one stout head log- heads, arms, legs, entrails, all mixed in a promiscuous mass.” ~ Private William Taylor, Co. D, 99th Ohio

Night, a dark and dreary night,

followed the day and the rain which had been moderate during the day poured

down in torrents. Tired and exhausted, our men slept on the field while the

Rebels dragged themselves along retreating from the place they were so

confidently told was within their grasp. The morning of the 17th,

the bugle sounded reveille at an early hour. Our army was in motion marching

after the retreating foe. Soon artillery could be heard miles in front as our

cavalry came upon the rear guard of Hood’s army. Our corps was in the rear and

marched but a short distance. It rained a cold wintry rain, the mud was deep

and growing deeper, yet the men murmured not as they were eager to come up with

the Rebels and finish the good work already begun. They were flushed with

victory while the Rebels were depressed by defeat. At night we were again out

in the rain, many without blankets. It was hard soldiering but must be done.

On the 18th we again

moved forward, but the whole army had come on to the Franklin Pike and it had

almost ceased to be a pike from the heavy trains which had gone over it. The

weather remained inclement: it rained, it snowed, and sleeted alternately and

the wind blew piercing cold from the northwest. This day we reached the Harpeth

River opposite Franklin. There was but a single bridge and day and night, the

troops, wagons, and artillery were crowded over it. We camped without crossing.

During the day we had been meeting captured artillery and prisoners coming back

from the front. Each fresh crowd of Rebel prisoners brought forth remarks from

our men and retorts from them. Some of our men would ask the Rebels if they

were going to take Nashville; they would answer pleasantly yes while another

would ask why don’t you take Nashville? A snappish Rebel would reply why don’t

you take Richmond? One would “where’s Hood?” I heard the reply given that “he

told us he would go to Nashville or hell, and he’s got the hell end of the

road.” The prisoners appeared generally pleased that they were captured and

frequently asked if hardtack was plenty in Nashville. They said they had been

living on parched corn and beef alone.

Our army has captured since we left Nashville more than 8,000 prisoners and 61 pieces of artillery. No small victory with a fine prospect of still further fruits resulting from it. I am in hopes this campaign will soon close and we will be permitted to rest until spring opens. But if any good can be done to the cause by the continuance of active operations, I am willing to do my share. You may think we move slow, but if you could only see the roads and know that we must bring up rations and ammunition, you would not think so.

Source:

Letter from Lieutenant Colonel John E. Cummins, 99th Ohio Volunteer Infantry, Sidney Weekly Journal (Ohio), January 6, 1865, pg. 2

Comments

Post a Comment