Onward to Chattanooga is the Cry: With Sheridan’s Provost Guard at Stones River

By 7 o'clock on the morning of December 31, 1862, the fighting at Stones River had already turned seriously awry for the Federal army. As Richard Johnson's division began its retreat, hundreds of men fled north towards the rear where they were stopped by the provost guards. One of them, Private Otis W. Strong of the 44th Illinois, described this discouraging task.

"The provost guard of each division was ordered to the rear with pointed bayonets and loaded rifles with orders from General Rosecrans to bayonet or shoot every straggler that made his appearance," Strong remembered. "Being mostly new troops and the battle raging with all its fury, back they would come and back they were forced into the fight. One poor fellow came back on the full run and it became my duty to halt him, asking him at the same time if he was wounded. He shouted, “Let me go, let me go! I am demoralized as hell!” and, in his own language, if this war continued much longer we shall all be as “demoralized as hell!”

Private Strong's account of Stones River originally saw publication in the Adrian Watchtower published in Adrian, Michigan.

Right Wing Hospital, near Murfreesboro, Tennessee

January 6, 1863

Dear friends,

Scarcely had

my last letter gone to mail before we received orders to attack the enemy which

was supposed to be three miles distant. And accordingly at daylight you could

have seen 75,000 soldiers winding their way among the hills and dales. At about

10 a.m. heavy cannonading was heard in our front and upon arriving at Nolensville,

nine miles from Nashville, a desperate fight with 2,000 of the enemy took place,

routing them and taking several cannons. Here we lay our weary limbs down upon

the wet ground until daybreak when on we went pell-mell after the enemy,

skirmishing and shelling the woods as we went until we advanced eight miles

where the Rebels again made a short and desperate stand. But again, they were

obliged to retreat, tearing up the bridge after them which we soon rebuilt Here

we lay over for the Sabbath.

Monday at

daylight we again started on our march to Murfreesboro. At about 3 p.m. we

entered the famous cedar swamp some ten miles through and Oh ye God, what a

place! Darkness came and with it torrents of rain and I have never saw such

darkness before. Scarcely a sound was heard except sullen rumble of the wagons

over the roots of the cedars or a terrible imputation of some poor soldier who

had come up standing against a cedar, the consequence being a bruised shin.

Kentucky boasts of her Mammoth Cave, Virginia of her Natural Bridge, why not

Tennessee her Cedar Swamp? Yet on we went until midnight bound for the front.

We all felt joy but it was of short duration as we were informed that the enemy

was 75,000 strong upon the rising ground in front; also that General McCook’s

staff had nearly all been shot down from their saddles when in the advance. But

by this time our army had all passed through the swamp and encamped directly in

the face of the enemy.

|

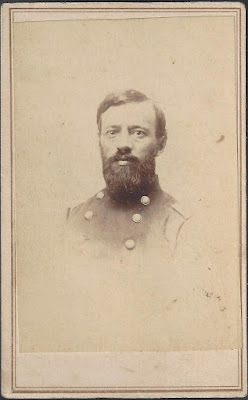

| Colonel Wallace W. Barrett 44th Illinois |

Here we lay

upon our arms until daybreak when the infantry commenced moving forward as the

enemy gradually fell back. At about 10 o’clock the fighting became general

extending some six miles. The roar of the cannon and volley after volley from

the infantry gave us to understand that the battle was raging with fury which

continued until after dark when, becoming weary, all was again quiet except the

sharp crack of the pickets’ rifles. About this time, myself and ten others were

detailed from the provost guard to advance in front and guard the hospital

which we did with dispatch.

All apparently

was quiet until daylight when- oh, that I might forget it forever. But this

cannot be. During the night the enemy had concentrated their whole force upon

our center and at daylight 5,000 Rebels came rushing upon us like demons. Our

forces fell back in the greatest confusion and here a regular Bull Run scene

was enacted, placing our hospital in a critical position directly between the

fire of two armies. The canister pierced the hospital in every direction.

Three times I volunteered to ascend to the top of the

building and extinguish the flames that had caught from the bursting shells.

The provost guard

of each division was ordered to the rear with pointed bayonets and loaded

rifles with orders from General Rosecrans to bayonet or shoot every straggler

that made his appearance. Being mostly new troops and the battle raging with

all its fury, back they would come and back they were forced into the fight.

One poor fellow came back on the full run and it became my duty to halt him,

asking him at the same time if he was wounded. He shouted, “Let me go, let me

go! I am demoralized as hell!” and, in his own language, if this war continued

much longer we shall all be as “demoralized as hell!”

Our troops continued to fall

back and the surgeon told us to take care of ourselves as best we could and we

were compelled to leave our poor wounded comrades to the mercy of the fiery

element which soon left but a smoldering pile of embers to tell their fate.

Twice during the day we were taken prisoners and retaken. We fell back one mile

where Rousseau’s division was drawn up in line of battle. And here the enemy

found their match, such fighting never before was witnessed. This continued

until dark. During the night the Rebels fell back a short distance and by

daylight the cannonading was terrific beyond description until about noon when

it gradually ceased.

|

| Civil War-era sword bayonet manufactured for use with the U.S. Model 1855 percussion rifle. |

But our work was not yet

accomplished. At about 4 p.m. the enemy threw his whole force upon our left

wing, determined to break through, but troops being on the alert were prepared

to give them a warm reception and for two hours the fight was again terrific.

It really seemed as if the fiery elements of the eternal world were upon us

during the short engagement. It is estimated in official circles that 2,000

fell to rise no more; two regiments of Alabamians were brought in besides

plenty of small squads. Skirmishing was kept up during the night and our

cavalry made a bold dash upon their pickets, taking some cannon and prisoners.

This being the Sabbath, it is

very quiet. It is reported that the Rebels have skedaddled. Our loss during the

eight days’ fight is frightful, perhaps not less than 20,000. Our regiment (the

44th Illinois) is nearly annihilated. Our regiment reports 241 men

for duty, our company making 31 of the number. When we left Chicago, the

regiment numbered 1,003, our company reported 104 good men. Not more than one

company of the 21st Michigan is left while 25 men of the 2nd

Missouri is all that report for duty. Other regiments suffered accordingly.

All of our brigade commanders in

the division were killed the first day, yet I think the enemy’s loss will greatly

exceed our own and thus far we can claim a great victory over the combined forces

of the Southern Confederacy; not, however, without causing the bitter tears to

flow from many a fond parent or loving sister in their far-off homes made

lonely by the absence of loved ones. We have marched eight miles since I

commenced writing this and “Onward to Chattanooga” is the cry.

|

| Detail of the lockplate, trigger, cone, and rear sight of a M1851 Saxon rifle similar to those issued to the 44th Illinois early in the Civil War. (College Hill Arsenal) |

Source:

Letters from Private Otis W. Strong, Co. D, 44th

Illinois Volunteer Infantry, Adrian Watchtower (Michigan), January 21,

1863, pg. 1 and February 14, 1863, pg. 2

Comments

Post a Comment