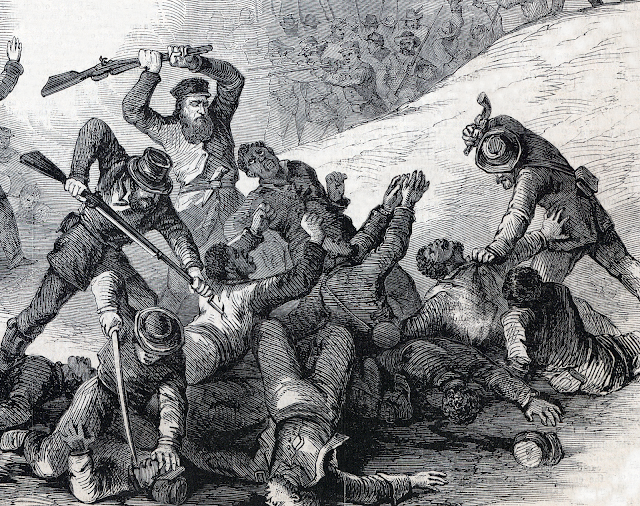

Blackest Deed of the War: A Woman's Impressions of the Fort Pillow Massacre

On April 13, 1864, the steamer Platte Valley arrived

opposite Fort Pillow, Tennessee and stumbled across a scene that chilled the blood of its civilian

passengers. Scattered along the banks of the Mississippi River lay the bodies of dozens

of dead Federal troops. The story they learned once they reached shore one eyewitness

later characterized as “the blackest deed of the war.”

“All hearts were appalled with

horror as the bloody panorama unfolded itself to view,” one passenger noted. “The

fort presented a mass of flame and smoke as the storehouses, sheds, and other

buildings were in flames and the heaps of cotton burning with a peculiar lurid glare

lending a bloody glow to all around.” She soon learned from the survivors what

happened when the Confederates took the fort the day before. “They pleaded to

be treated as prisoners of war, but their murderers reviled and cursed them,”

she wrote. “After all the white men except those on our boat were killed, the

Negroes left were ordered to bury the dead in the trenches. They were then made

to dig a ditch for themselves and were shot and thrown into it.”

It is unfortunate that the full name of this eyewitness to the Fort Pillow massacre has been lost to history. The Illinois State Journal identified her as “a lady now in this city who was a passenger aboard the Platte Valley and who was a witness to many of the outrages perpetrated by the Rebels and received statements concerning others from the wounded soldiers.” Her account is signed E.G.P. and first saw publication in the April 18, 1864, edition of the Illinois State Journal published in Springfield, Illinois.

Having been an

eyewitness of the terrible scene at Fort Pillow after the late massacre, I will

endeavor to give as nearly as possible facts which came within my own

knowledge. The steamer Platte Valley left Memphis Tuesday evening April

12th accompanied by a gunboat [No. 27]. About 10 o’clock in the evening,

another gunboat passed us going down with holes through her cabin and chimney

and her officers informed us that Fort Pillow was in possession of the Rebels.

At 9 o’clock the next morning we

were in sight of the fort and our gunboat went head to reconnoiter while we

anchored in the middle of the river not daring to land. Presently our gunboat began

throwing shells but no answer came from the fort. Again, and again our guns

boomed out and after several shots we could distinctly hear volleys of musketry

on shore but not directed toward the river. This we learned afterward was the

firing upon our remnant soldiers by their brutal captors. Suddenly, we saw the

gunboat cross the river and approach the shore under the fort at the same time

signaling us to come on. Approaching nearer, we saw a flag of truce on shore.

The gunboat ran up a white flag and landed.

Slowly we came to the scene of

desolation and murder. All hearts were appalled with horror as the bloody panorama

unfolded itself to view. The fort presented a mass of flame and smoke as the

storehouses, sheds, and other buildings were in flames and the heaps of cotton

burning with a peculiar lurid glare lending a bloody glow to all around. Up and

down the shore were scattered the dead Forty blue uniforms were counted shrouding

the dead bodies of the slain martyrs. In all positions they lay- many were

lying head downward at the bank at the edge of the water having been driven

backward to the river and then shot or stabbed till they fell. About 300 blacks

had been driven into the river and drowned.

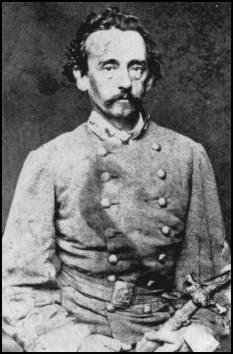

In the background, amongst the hills,

were seen groups of guerillas and horses. In the foreground stood General James

Chalmers in consultation with the commander of our gunboat while apart on one

side were several Rebel officers, some on foot and others mounted. We noticed

the bandit aspect of these men particularly well-dressed in gray uniforms and

thoroughly armed, their attitude and manner betrayed the ease and nonchalance

of men accustomed to robbery and murder and every movement revealed a

callousness to suffering and familiarity with blood and outrage.

The interview being ended

between the two commanders, our officers came on board and announced that the

enemy would allow an armistice until 5 o’clock (it was now 11 a.m.) and that

meantime we would be granted the poor privilege of bringing off our wounded and

burying the remainder of our dead. In a moment all was ready and the work

began. Carefully and tenderly our butchered soldiers, barely alive, were

brought on board and placed on the cots provided by the humane officers of the

boat and those who witnessed the sufferings and looked upon the wounds of our

brave men that day were thrilled with the horror and aroused to a thirst for

vengeance unknown before and not to be imagined.

While the sad work progressed,

General Chalmers came on board to drink at the bar and seeing him closely, I

discovered that chivalry consists in a handsome suit of gray ornamented with

silver stars and gracefully worn, a drab cavalier hat and long black plumes

with gay sash and glittering arms. This stylish looking villain raised his eyes

as he passed me with as much court-like ease and grace as if he had been at a

ball room and bowed until the plumes of the hat held in his hand trailed on the

floor. With a look that would have murdered him where he stood if looks had the

power to kill, I met his glance. It was apparent to all that he was fully

conscious his courtesy was resented as an insult, for he changed countenance,

dropped his eyes, and passed on.

At noon he came on board again

accompanied by his staff and was invited to dine by some Union officers,

passengers on the boat. I regret that I cannot give the names of these men who

disgraced their uniforms so wantonly while our murdered men were lying bathed in

blood before their eyes. These Union friends of their country’s foes had Rebel

wives who received the illustrious butcher with cordiality and delight, and I

heard Chalmers exclaim that it did him good “to shake hands with thorough Rebel

ladies once more.” He showed his sword, declaring that he took it from Grant’s

Inspector General and said he came near capturing Grant himself at

Colliersville, betraying by his remarks how little he was aware of General

Grant’s whereabouts at that time. He announced carelessly his intention of “taking

Memphis next” as if it were a mere matter of taste when he should occupy that

city and expressed his gratification that his Rebel friends had escaped in

time. He is in every respect a specimen of the chivalry, all words and

braggadocio, and full of admiration for himself.

|

| Western Confederate cavalrymen |

The wounded not being so

disposed that we could administer to their wants, their wounds were dressed,

food and drink given them, and everything possible done for their comfort. A

total of 36 white men and 21 colored were the remnant left from 600 troops,

saying that 40 prisoners were taken away. They told me the attack was made just

before sunrise, the fort being occupied by nearly 300 white men from the 13th

Tennessee Cavalry and the rest black troops from the 6th U.S.

Colored Heavy Artillery.

The fight lasted until 5 p.m.,

the garrison refusing to surrender when treacherously and in true chivalric

style, the enemy under a flag of truce moved up the defiles in the rear of the

fort and stormed it. Up to this time, only eight or ten men had been hurt, but

now the massacre began, our men having thrown down their arms and given

themselves up. They pleaded to be treated as prisoners of war, but their murderers

reviled and cursed them, pursuing their bloody work, robbing our men of their money

and valuables, and thrusting their hands into the pockets and breasts of our

soldiers to be sure they had given up all. After all the white men except those on our

boat were killed, the Negroes left were ordered to bury the dead in the trenches.

They were then made to dig a ditch for themselves and were shot and thrown into

it.

“When the Rebel charge commenced, nearly all the colored troops left the fort and in attempting to escape fell into the surrounding lines of the enemy who commenced the most inhuman, deliberate, and cold-blooded slaughter that has ever yet disgraced the annals of civilized warfare. The Negroes were pursued even to the river and into the water and there murdered unarmed in great numbers and without mercy. When the enemy entered the fort, he there commenced indiscriminately the work of death upon the gallant white troops and continued it long after they were disarmed and prisoners.” ~passenger aboard Platte Valley

The following morning the

shooting of the Negroes was resumed and many who had escaped the night before

were now discovered and met their fate. The Rebel surgeons offered to do

something for our wounded, but their officers forbade it, at the same time

shooting down some Negroes who had ventured not the quarters. It is beyond

question that the few suffered to live were spared as a show of humanity and

these were so mutilated and nearly all the wounds will prove fatal. Eight died

before we reached Cairo and not more than will probably survive of the remainder.

The wounds are all of the most terrible and fatal character. Some of the saber

gashes were frightful; eyes shot out, heads laid open till the brain oozed out,

and some of the men had from five to nine wounds. The legs of one man were both

crushed and one boy not yet 15 had both legs and his back broken. Scarcely any

had less than two or three severe wounds.

There is no doubt the murderers

intended everyone should die. Nearly all the wounded could talk when first

brought aboard and they all told the same story. There were no contradictions

in their statements, and everyone assured me he was unwounded when he gave

himself up as a prisoner. The hospital was fired and the sick and wounded

burned without mercy and one sick man brought on the boat who had escaped told

me himself that the Rebels came into his tent and deliberately set fire to it.

The men all assured us that Chalmers did not take more than 40 prisoners and

some thought not more than 20. The prisoners were drawn up in line and marched

off under the eyes of the wounded who say that no artillery officers were among

them.

“Our men were so exasperated by the Yankee threats of no quarter that they gave but little. The slaughter was awful. The poor deluded Negroes would run up to our men, fall on their knees, and with uplifted hands scream for mercy, but they were ordered to their feet then shot down. The white men fared but little better. The fort turned out to be a great slaughter pen. Blood, human blood stood about in pools and brains could have been gathered up in any quantity.” ~Sergeant Achilles V. Clark, Co. D, 20th Tennessee Cavalry, Forrest’s command

The officers of the Platte Valley

placed the boat at the disposal of the suffering soldiers and Major O.B. Damon,

a naval surgeon, is entitled to much respect and gratitude for the skill and

tenderness shown the wounded. He is a very noble man and devoted himself day

and night to his sad but humane work assisted by many of the passengers. The

wounded men bore up bravely and cheerfully, constantly expressing their

gratitude for every kindness and attention and enduring without complaint the

most fearful agonies. They assured me they did not dare to surrender until

compelled as the Rebels would not agree to spare the colored troops and the

white soldiers were nearly all deserters from the Southern army.

I have given you simply a statement of reliable facts gathered carefully from those in the fight and which may be depended upon. Many persons can testify to the burning bodies seen in the fort and other evidence of the brutality and fiendish barbarities perpetrated by the murderers of Fort Pillow. The massacre stands without parallel- words can give no adequate idea of the blood and destruction. Evermore the place will be held in horror and known as the spot where the blackest deed of the war recorded itself.

E.G.P.

Sources:

“The Fort Pillow Massacre,” Illinois State Journal (Illinois), April 18, 1864, pg. 2

“The Massacre at Fort Pillow,” Illinois State Journal (Illinois), April 19, 1864, pg. 2

Sheehan-Dean, Aaron, ed. The Civil War. The Final Year by

Those Who Lived It. The Library of America. New York: Penguin Books, 2014

Comments

Post a Comment