On the March in Earnest and Full of Fight: An Illinois Bugler Marches to Murfreesboro

English-born Charles Lewis Francis marched towards

Murfreesboro as a bugler serving in Company B of the 88th Illinois

Volunteers under the command of Colonel Francis T. Sherman. His account of the

Stones River campaign is remarkable for not only its candor but its attention

to detail and is one of my favorite accounts describing the opening days of the

campaign. This excerpt is drawn from Francis’ book entitled Narrative of a Private

Soldier in the Volunteer Army of the United States During a Period Covered by

the Great War of the Rebellion of 1861 which was published in 1879.

On Christmas

morning we had received our orders and were ready. We had all written to our

friends in the North, many for the last time, and exchanged our fine Sibley

tents for the new shelter tents. The $2 per man that the general government allowed

as an enlistment premium and which had been retained by our company patron (the

Chicago Board of Trade) and by him expended had come back to us in the shape of

an excellent rubber blanket apiece. On the morning of the great Christian

festival, we broke camp and made an advance of about a mile where we

established a strong outpost and went no further. It was said that General

Rosecrans was not ready. He was a good churchman and did not believe in

fighting on Sunday nor in undertaking a movement on a holy day. This was the

talk amongst the soldiers and I only give it as such.

The next day,

however, we were on the march in earnest and full of fight. We were much

lighter baggage than we had previously been and we met the enemy before we were

an hour from camp. Sheridan’s division to which my regiment (88th

Illinois) belonged went through Nolensville with a rush. I had just time to notice

that Nolensville consisted of about half a dozen miserable shanties; the most

pretending seemed as if it might have been a schoolhouse but the same sign over

the door with the legend ‘Tippling House’ upon it dispelled such illusions.

The road thence led up a strong

and steep hill and as it got on toward the top it was wooded on either side. In

the woods and half a mile ahead of us, an Ohio regiment had a lively fight in

the afternoon (see "Charles Barney Dennis at Stones River part 1" here) and succeeding in

driving the enemy besides capturing two English rifled cannons, a few horses, and

several prisoners. The enthusiasm of the army was well-nigh unbounded at this

success so near the outset, and although we were formed into line of battle not

far to the rear, we were envious of the regiment that had the honor of being in

front of us.

That night we laid on our arms

in an open field on the left of the road and near the foot of the rising ground

but protected in a measure by some heavy woods near us. The light drizzling

rain that had been falling all the afternoon had increased to a torrent, but

the excitement engendered by our proximity to the enemy served well to keep up

our spirits. Besides this, our new arrangements for camping were admirable. Two

men slept together. One rubber sheet on the ground and a woolen blanket on

that, then another woolen blanket on top with the shelter tent and rubber on

the outside. In this manner two men were effectually protected.

On the next two days, we

skirmished with the enemy continually and our regiment came in for a good share

of the hard work. Our company being on one of the extremes of the line, it was

usually deployed when skirmishing duty was demanded and so I had plenty of

opportunity for using my bugle. The road we were on had a macadamized bed and

would have been a good one to travel upon had it not been for the excessively

wet weather; as it was, the surface in level places was nearly ankle deep in

liquid limestone.

On Saturday night it was

reported that the enemy had changed front and formed his new lines in another

direction between Stones River and the town of Murfreesboro. It had been

raining all day and the night promised to be only murkier and gloomier than the

wearisome day had been and when we ascended the hill on the right of the road,

the men felt in any but elevated spirits. Just as we had received orders to

stack arms in the place selected for our bivouac, the sky cleared just above

the western horizon and for the space of about half a minute the sun appeared

in indescribably great glory then vanished. This was instantly taken as a good

omen and the drooping spirits of the soldiers rose at once and the army gave a

tremendous shout that rent the air; the noise of that cry from tens of

thousands of throats far exceeded the uproar of the great battle fought a few

days after and, as the shouting was echoing from the clouds as it were, the

incident was awe-inspiring. This lasted, however, for only such a little while

and we sank upon the wet grass to rest our weary limbs and to eat what was left

of our three days’ rations.

The next morning (Sunday

December 28th) was clear and cold and we heard with dismay that the

enemy’s cavalry under Wheeler had intercepted and cut off our supply trains

from Nashville. It was again given out that General Rosecrans would not follow

the new direction on Sunday and we were to have rest. But rest without rations

was not so good a thing. Early in the morning, an order was received by each

company commander to send six men on a foraging expedition for his company:

this was the first legalized gobbling that I had seen. In a wondrously short

time after the order was received it was executed and more than executed with

spirit and alacrity. Instead of detailing six men out of each company, most of

the company left just that number behind and no more, the rest going out as

foragers.

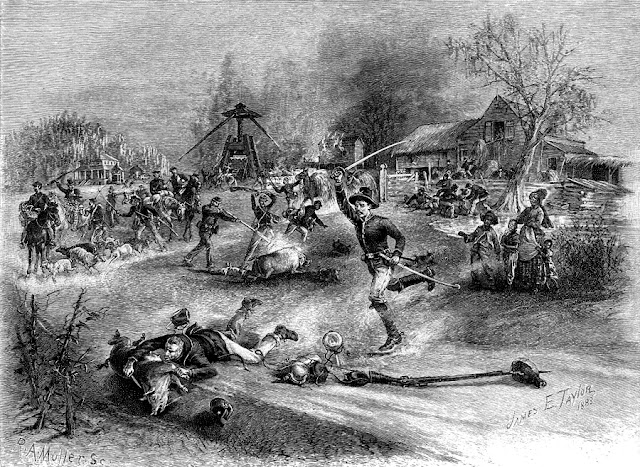

Foraging is the name when

legalized and gobbling when not. Of this particular expedition, I can only

describe the part taken by the squad I happened to be with. We went through the

woods, over hills, across bottoms, through fields, and over rivulets for a mile

or more to our right and front without meeting any prospects of success. Then

the incorrigible Tommy Corrigan who was some distance in the advance made a

loud exclamation that told us he was not far from a prize and we saw at a

distance of half a mile a large substantial mansion and numerous outbuildings.

We hastened our steps and after clearing numerous ditches and fences, we

entered a long lane in which we formed into line with Tommy Corrigan on the

right as undisputed commander.

We soon reached the place and as

an institution found it to be greater than many of the towns we had passed

through, although the latter generally boasted high-sounding names. The mansion

itself was a large two-story wood building and had the inevitable hall running

through the center of it and immense chimneys built on the outside of each end.

The second story was almost an exact company of the first. A sort of porch ran

up to the roof and the door leading into it from the second story was exactly

like the front door below, even to the knocker. There were numerous outhouses,

granaries, smokehouses, stables, root-houses, and henneries on one side of the

main structure and on the other a village of Negro huts lying low and irregular

like so many smashed tiles.

Before we got to the lawn

entrance, we met a Negro man who was nearly scared to death and he came toward

our position fairly dancing with fear. From him we learned that his master was

a Rebel of the deepest dye and only the night before he had captured a Union

soldier and had conveyed him to Murfreesboro where the poor fellow was to be

shot for being a spy. The master was “cruel to his slaves” as well as he had

shot or hung several of the Negroes who had attempted to get away.

We now held a council of war and

having informed ourselves of the nature of the surroundings as to the number of

the inmates, locality of the provision stores, etc., we advanced towards the

house. When we entered the gate, we saw a fat, jolly looking old planter

standing in the doorway of the house. He was perhaps 60 years of age and

appeared as if during the whole of that period he had lived upon the best that

the land afforded. But he had a gun in his hand and as Tommy Corrigan drew a

musket to his shoulder, he gave the command ‘drop that piece’ and the piece was

dropped as if it was red hot. Then we advanced and seized the old gentleman. He

was very belligerent- in fact, full of opposition- but we soon disarmed him and

set a guard over him some distance away from the house.

On ransacking the place, we

found the planter’s wife and two daughters. They boastingly told us that the

husbands of both of them were in the Southern army and would revenge any injury

we might do. We tried in vain to make them understand our situation as we were

only after forage and intended no harm to them personally. We could do nothing

else other than order them out and place them under guard with the husband and

father. On closer inspection we discovered the uncleansed dishes in the kitchen

amounted to more than would ordinarily accrue from a meal of four persons and

this led to an examination of the old man. He boasted of his capturing the

Union spy and threatened that belong long the Confederates who had breakfasted

with him that morning would return. If the old man told the truth in his

violence, he was the most brutal enemy I had yet met. He confessed to almost

every offense a war Rebel could be charged with.

The old man was given ten minutes to secure what he wanted out of the house. This he refused to accept; neither would the women secure anything. They were then bound, the Negroes ordered to the rear, and the plethoric meat house was plundered. When we returned, the provost guard took charge of our prisoners. We made the Negroes beasts of burden and they carried our plunder of corned hams, bacon, sausage, meat, potatoes, apples, etc. For hours on that afternoon and evening, we were engaged in frying our meat and cooking the rest of our confiscated rations.

Source:

Francis, Charles Lewis. Narrative of a Private Soldier in

the Volunteer Army of the United States During a Period Covered by the Great

War of the Rebellion of 1861. Brooklyn: William Jenkins and Company, pgs.

93-100

Comments

Post a Comment